Unflinching Voice of Resistance to White Power Structure Echoing from the Era of L.A. Rebellions

by Mesay Berhanu Gemechu

Film has remained a battleground for very long, where contending ideologies, traditions, and identities

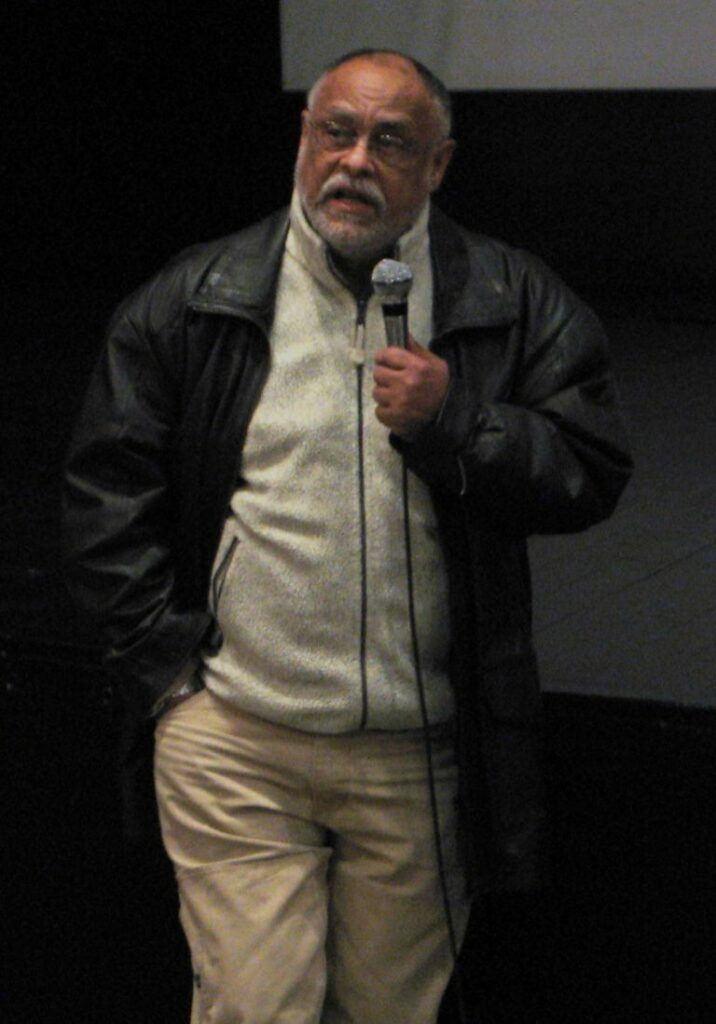

came to find expressions at the expense of one another. It continues to serve as a “nuclear weapon” as described by some circles among the Latin American filmmakers. In this war of images and labels, Hollywood, the largest film machinery in the world, is accused of being an apparatus employed by the white power structure to maintain cultural hegemony over all the other alternative manifestations. A generation of filmmakers labelled as the L.A. Rebellions have fought back this monopoly of cultural narratives using the same weapon. Among them is the prominent Ethiopian filmmaker, Haile Gerima, whose films earned him international recognition and is unflinching in his criticism of the white power structure prominently and consistently portrayed in the Hollywood film traditions.

His latest movie, Children of Adwa 40 Years Later, continues to recounts the story of another episode of black resistance to the Italian occupation in Ethiopia during the WWII, depicting the brutality of the invading forces using authentic footages taken on spot from the same era.

—–

Haile Gerima is a founding member of the black film movement among a generation of filmmakers

including Charles Burnet (Killer of Sheep), Jamma Fanaka (Penitentiary), Ben Cadwell (I and I), Larry Clark (Passing Through) and Julie Dash (Daughter of the Dust). They came together to produce films unlike the Hollywood productions to reflect the true colors of their own cultural background and historical identity. The group labelled as “the L.A. Rebellions” attended the UCLA School of Theatre, Film and Television. But they have chosen to break away from the dominant tradition of filmmaking embodied in the Hollywood film industry which they have seen as a machinery to perpetuate the racist socio-economic structure upholding white supremacy.

Since then, Gerima has remained an ardent critic of the Hollywood film industry which he pointed out to

be a machinery employed to perpetuate the White power structure embodied in the U.S. and the European model of socio-economic arrangements. Hence, he said it is the responsibilities of filmmakers like him who came from a different socioeconomic background to reflect their own traditions and identity in the films they are making. Similarly, as an African, it was his responsibility to reflect his African identity and traditions in the films he made. He makes films to reveal the missing images of the black history and traditions emanated from his African roots often left out or misrepresented in the standard Hollywood movies. His films serve as authentic records of the heroic resistance of the black communities against the white power structure stemmed from colonial traditions, upholding the idea of freedom and black identity critical to building one’s own character as well as encourage innovative approaches in filmmaking as a critical response to the standard Hollywood practices.

The dictatorial arrangement in Hollywood locks out independent voices like Gerima which he asserts is

not a result of individual choices as a human being but a result of the dominant mindset in the industry.

When asked in the Hollywood context what would be the point of entry in a proposed film production, it would often mean who the white character would be to pair with and amplify the native characters in that story. For Gerima, that is a blatant racism. “It is a very bad arrangement when you are dealing with a race issue. It keeps holding your story hostage to paternalism, and therefore, the very objective of wanting to break barriers and bring human beings together gets compromised,” Gerima reflected in an interview with Aljazeera in 2009.

His first encounter with race issues in Chicago was when he realized that his own humanity was negated in a country where his existence was completely omitted, where he was denied the recognition to be a person. This made him doubt whether he was indeed regarded as ‘a quality human being’. That was why he escaped to L.A where he studied movies and found the creative expressions in making movies to explore his own identity and vent his dissatisfaction with the existing structure dominated by the ideals of white supremacy.

Black Identity and Resistance in Movies

Coming from a humble background, a small town in Gondor in the northwestern part of Ethiopia where he was born and raised, Gerima went to the U.S. at the age of 21 where he studied films and started to work as a professor at Howard University for the past several decades. Meanwhile, he continued to garner international recognition and awards for quite a number of his works notably the 1993 film, Sankofa.

Sankofa (1993) is a particularly noteworthy film Gerima has ever made as a writer, director and

producer to capture the resistance nature of the African Americans who were brought to the U.S. in

slavery. The film received a wide range of international recognition and awards, including the Agip Grand

Prize at the African Film Festival in Milan, Italy, and the Best Cinematography Award at the FESPACO

Film Festival in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. The film was also nominated for the Golden Bear award in

the 43rd Berlin International Film Festival held in February 1993.

Sankofa focuses on a female character, Mona, a representative of the modern world, who transported

back in time to depict the life of Shola, a slave woman on the Lafayette slave plantation to expose the

brutality of slavery at the time. Gerima received criticism from certain corners for the graphic scenes in

the film which was noted as particularly disturbing unlike other films in the same tradition. Despite such

criticism, the film received a wide recognition and favorable acceptance particularly among the black

community in the U.S. who crowded in the cinema halls when the film was featured in the various cities

across the country.

However, film distributing companies in the U.S. did not show an interest in Sankofa despite the fact

that tickets were sold out in various places when the film was first released in 1993. Gerima then went

on to establish a cultural center under the name, Sankofa, located across Georgia Street 2714 in Washington, D.C. near Howard University where he had been teaching for more than five decades. The

center serves as a venue to present films, organize book launching and signing ceremonies, and hold

discussions on various topical issues. Gerima in partnership with his wife, Sirkiana Aina, a film

professional on her own right, also established earlier in 1984 Mypheduh Films, Inc. to distribute low

budget and independently produced films, from which he was able to generate parts of the fund he

required to produce his film, Sankofa.

Gerima spent nine years to raise the money for Sankofa and it took him even longer to complete the

production of Teza that was carried out in a span of 14 years. He considers it a waste of time to look for

funding in the U.S. to finance his movies which focus on the kind of issues he is interested in– African American or African subject matters which would not have a chance to attract financing opportunities in the U.S.

“My film projects are projects that I feel I would like them to exist along with all the other stories told

without coming at the stories saying, ‘Are they credible? Can they sell? Would people watch them?’

These are things that sensor stories from people. So, what I do is I don’t ask those questions. I say I am

angered for the story so I go out of my way for years to find the money to do them,” he asserted in an

interview with ResearchChannel in 2006.

—–

When he first came to the U.S. in 1967, Gerima was influenced by Latin American films of the 1960s and

1970s which shaped his career trajectory as an independent filmmaker and a vocal critic of the Hollywood traditions.

Haile Gerima realized the power of films which was regarded among Latin American filmmakers as

equivalent to that of an atomic bomb in the sense that it has been used as a weapon to destroy the

historical and cultural identity of the black community and people in Latin America and other parts of

the world, which Gerima refers to as “cultural genocide”.

In a conversation on Black Aesthetics Gerima had in Philadelphia in 2016, he candidly declares, “Don’t

take me as a film lover. I don’t love cinema. I hate cinema. Don’t take me like a cinema-lover. I hate

cinema. It is a weapon used against my people. The most powerful weapon that disfigured African

people from Africa to Brazil. I can’t love it but I want to use it against itself.”

Gerima recalls how watching those Hollywood productions such as the Tarzan movies series had a subtle

but powerful influence on the psyche of his peers at such a young age when they were fully engrossed in

the stories in favor of the heroic actions of the white cowboys against fellow Africans as well as Indians

represented (or rather misrepresented) in the stories.

“It is just your accent, your temperament altering it to speak like those movies they have made

standards itself is almost cultural genocide. To me all human beings have very unique accent in the way they tell the story so the thing is not the theme. The theme is universal.”

Gerima was born to a mother who was a school teacher and a father who used to write books and direct

theatrical performance at his home town in Ethiopia. As one of the ten children in the family, he chose

to follow the footsteps of his father in telling stories reflecting his cultural identity and historical legacy

as an Ethiopian as well as a black African living in the U.S. He also developed his passion in storytelling

when his grandmother used to tell the children stories of animals and historical events as they gathered

around the fire at night before electricity was brought to their village. As a result, he grew particularly

cognizant of the power of storytelling to build the identity of the individual on the basis of shared values, cultural and historical heritages and form a strong social bond between the one telling the stories and those listening to them.

For him, “Story telling is healing and it exorcises I would say the negative aspect of your life because all

of us come with good and evil and I think storytelling therapeutically they strip out of your system the

evil aspect of being human. They are therapeutic and, in the end, this is really how I see film itself.”

Still, Gerima does not consider himself in any way as representing one segment of a society in his role as

a story teller through moving pictures, even though he realized his responsibility to gather the untold

stories reflecting the unique cultural identity and historical accounts from his past as a member of the

black African community of Ethiopian origin.

Gerima is critical of white people in general whom he regards as spoiled since, as he puts it, everybody who intends to make a movie is trying to appease them. It is like a requirement to bring on board a white character in a movie in order to make the film commercially more viable. Gerima calls this formula a trapping developed by Hollywood to have a white person to pair with the main character in a film even in historical movies set in a completely different sociocultural background. Therefore, he asserts his views, “I think by and large there is a whole corrupting implication that has come with the whole idea of white supremacy in cultural outputs. That I refuse to accept.”

He still acknowledges the presence of some progressive and courageous inquisitive white people who

are willing to cross over the race barrier to engage with the kind of stories presented in the likes of his

movies.

Even though his films are preoccupied with the history and identity of black people in general, he still

does not make films to appease even those black people themselves whom he says are the ones most

uncomfortable with his movies. He does not make movies intending to release the whites from their

responsibility as often is the case with many other black filmmakers who are engaged in a critical portrayal of black characters intended to appease white characters for many different considerations.

By the time he completed his studies at UCLA, Gerima already produced four films including Hour

Glass (1972), Child of Resistance (1972), Bush Mama (1975) and Harvest: 3000 Years (1976) among which the later one received numerous awards including the Silver Leopard award at the Locarno Film Festival in Switzerland.

Among his award-winning films is also included Ashes and Embers (1982) which portrays the challenges

of urban lives for young black people in the U.S., focusing on the life of a Vietnam war veteran who

struggles with depression and despair. The film was presented at the Schomburg Center for Research in

Black Culture in Harlem, New York by ARRAY which is dedicated to bring about narrative change through the promotion of African American Film Festival Releasing Movement (AFFRM).

Gerima is particularly notable for the idiosyncratic ways he shot his movies, which may be criticized as

unconventional and deviant from the standard practice in the film industry.

Bush Mama (1979) tells the story of a black woman, Dorothy, and her husband, T.C., a veteran from the Vietnam war who was incarcerated for a crime he did not commit. As a result, Dorothy had to deal with the emotional, moral and financial crisis of giving up on her baby in her womb if she wished to continue to receive welfare benefits to support herself and her only daughter. The film reflects the institutional racism in the US welfare system, and reveals police brutality against the black community which permeates the American society. This, as graphically demonstrated in the recent incident in Minnesota involving a 46-years old black man, named George Floyd. Floyd was choked to death by a white police officer pressing down his knees against his captive by the neck who was unable to breath while laying down on the ground, a scene captured on video and went viral on social media platforms. The incident sparked a worldwide protest against police brutality in the U.S. This has still continued to

claim the lives of more than 1,068 people across the U.S. in just one year after the incident, an average of three killings a day, according to data compiled by Mapping Police Violence, a research and advocacy group.

Wilmington 10 – U.S.A. 10,000 (1979) which was a documentary film described as a masterclass in

documentary filmmaking relates the story of ten young black men and one white woman, almost all high

school students who were wrongly convicted in 1971 for arson of a white-owned business in North

Carolina. The film not only exposes the racism in the U.S. justice system but goes well beyond the

presentation of mere facts to an exploration of human characters to show their struggle for justice. His other film After Winter: Sterling Brown (1985) is a documentary of the life of the great American poet and a leading member of the Harlem Renaissance.

….

Images of His Ethiopian Roots

Gerima’s latest film, Adwa 40 Years Later (2023), recounts the struggles of the Ethiopian patriots fighting against the Italian invading forces which occupied some parts of the country including the capital city between 1936 to 1941 to retaliate the humiliating defeat they had suffered at the Battle of Adwa 40 years earlier in 1896, then considered as an army of uncivilized black people led by Emperor Minilik who reigned from 1889 to 1913. The six hours long film is presented in five parts. Gerima uses authentic footages taken on spot by the Italian army and other professionals from Russia to recapture the spirit of the resistance struggle and the brutality of the Italian forces which indiscriminately used chemical weapons against the civilian population in parts of the country. Gerima lamented that such atrocities sadly remained unaccounted for as “war crime” at an international court of justice unlike what happened to the Hitler generals from Germany post World War II.

Adwa: An African Victory (1999) was also a documentary film documenting the iconic victory of the

Battle of Adwa against the Italian colonial forces which remains symbolic for black resistance and

freedom among the black communities in the U.S. and across Africa and the Caribbean in their resistance against the evils of colonialism and slavery which have long undermined the economic and cultural empowerment of black people at both sides of the Atlantic.

Gerima also made films critical of the administrations in his own home country as shown in Harvest

3000 Years (1976) and Teza (Morning Dew) (2008). The former reflects the miserable situation of the lives of a tenant family who lived under the oppression of the feudal system of administration at the

time of Emperor Haileselassie I. Imperfect Journey (1994) was also a documentary film commissioned by the BBC to document the resilience of a generation of Ethiopians who witnessed the horrific atrocities followed the 1973 military coup d’etat which brought to power the Derge military junta, and the psychological trauma and emotional scar the people had to endure over the years that followed.

Teza (Morning Dew) was made with a production cost of USD 1.5 million. The film received the Jury and Best Screenplay awards at the 65th Venice Film Festival in Italy. It shows the disillusionment of the young generation of Ethiopians after the feudal administration of Haileselassie I was overthrown in 1974. Initially, the youth were caught up in euphoria and heighted optimism in the change of the status quo as the Derge military junta seized power taking such revolutionary measures in the dominant land tenure system declaring ownership of the land to the tillers.

The young Ethiopians studying in Europe and the U.S. rushed back to their homeland hoping to

contribute their share in the transformation of the country’s future. But upon arrival, they faced a brutal

and oppressive military regime determined to use the educated elites as instruments of its political power or face the consequences of their choice which might be either imprisonment or death. The central character, named Anberbir, who studied medicine in Germany, had his hopes dashed upon arrival back to his country as he was no longer able to find a safe refuge even in his own village where his family lived. The community in the village continued to face the brunt of the armed conflict that took place between the national army and rebel groups claiming to fight for the freedom of the people. His flight back to Germany could neither provide him the safe heaven he was hoping to find as he had yet to deal with the consequences of a racist mob attack that left him crippled the rest of his life.

At the age of 77, Gerima still hopes to continue making his independent movies regardless of the fact

that it would take him years to put the finance together to realize their productions. The stringent

financial constraints he is facing is no excuse for him to give up on writing film scripts. He still has a

handful in progress as he continues to explore the historical legacy of black resistance in the U.S. and the

oppressive political and economic situations back in his own home country. His works embody the spirit

of black resistance as he hopes to be remembered as a voice of resistance and freedom in the independent film traditions. In his views, this spirit of resistance should not be lost in the trails of the young and upcoming filmmakers who would continue to challenge the overwhelming dominance of the Hollywood film industry which upholds the imposition of the white power structure that still remains intact.

Mesay Berhanu Gemechu is a graduate of Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul, South Korea in the area of international development studies focusing on Africa. He served as deputy editor-in-chief of Addis Fortune, the largest English weekly in Ethiopia, and he was also the 2023 African Correspondent for the Korea-Africa Foundation representing his home country. Mesay is currently living in Seoul, South Korea. The writer can be reached at: gmesayb24@gmail.com.