The 79th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which took place on 6 and 9 August 1945, remains a grim reminder of the destructive consequences of nuclear weapons.

By Thalif Deen

The bombings are estimated to have caused between 90,000 and 210,000 deaths, of which approximately half occurred on the first day in Hiroshima.

But despite an intense global campaign for nuclear disarmament, the world has witnessed an increase in the number of nuclear powers from five – China, the United States, France, the United Kingdom and Russia – to nine, including India, Pakistan, North Korea and Israel.

Is the global anti-nuclear campaign an exercise in futility? Will the upward trend continue, with countries such as Iran, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and South Korea being considered potential nuclear powers of the future?

South Africa is the only country to have voluntarily given up nuclear weapons after developing them. In the 1980s, South Africa manufactured six nuclear weapons, but dismantled them between 1989 and 1993. Several factors may have influenced South Africa’s decision, including national security, international relations, and a desire to avoid becoming a pariah state.

But there is an equally valid argument that there have been no nuclear wars – only threats – due in large part to the success of the global anti-nuclear campaign, the role of the United Nations and the collective action of most of the 193 member states in adopting various anti-nuclear treaties.

According to the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA), the UN has been trying to eliminate weapons of mass destruction (WMD) since the world body’s creation. The first resolution adopted by the UN General Assembly, in 1946, established a commission to deal with, among other things, problems related to the discovery of atomic energy.

The commission was to make proposals for, among other things, controlling atomic energy to the extent necessary to ensure that it was used only for peaceful purposes.

Since then, several multilateral treaties have been established with the aim of preventing nuclear proliferation and testing, while promoting progress towards nuclear disarmament.

These include the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT ), the Treaty on the Ban of Nuclear Weapons Tests in the Atmosphere, Outer Space and Underwater, also known as the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) , which was signed in 1996 but has not yet entered into force, and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) .

Jackie Cabasso, executive director of the Western States Legal Foundation in the United States, told IPS: “As we approach the 79th anniversary of the US atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world faces a greater danger of nuclear war than at any time since 1945.”

“The terrifying doctrine of ‘nuclear deterrence’, which should long ago have been delegitimised and relegated to the dustbin of history and replaced by multilateral, non-militarised common security, has metastasised into a pathological ideology wielded by nuclear-armed States and their allies to justify the perpetual possession and threat of use – including first use – of nuclear weapons,” he said.

For the head of the foundation that monitors and analyzes U.S. nuclear weapons programs and policies, “It is more important than ever that we heed the warnings of the old hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors): What happened to us must not happen to anyone else; nuclear weapons and human beings cannot coexist.”

“No more Hiroshimas, no more Nagasakis!” said Cabasso, whose organization is based in Oklahoma, California.

This requires an irreversible process of nuclear disarmament, he argued. But he added that, on the contrary, all nuclear-armed states are qualitatively and, in some cases, quantitatively improving their nuclear arsenals, and a new multipolar arms race is underway.

“To achieve the elimination of nuclear weapons and a more just, peaceful and ecologically sustainable global society, we will have to move from the irrational ideology of deterrence, based on fear, to the rational fear of the eventual use of nuclear weapons, whether by accident, miscalculation or design,” said the legal promoter on nuclear disarmament.

He added: “We will also need to encourage rational hope that security can be redefined in humanitarian and ecologically sustainable terms that will lead to the elimination of nuclear weapons and dramatic demilitarization, freeing up tremendous resources desperately needed to meet universal human needs and protect the environment.”

Cobasso recalled that the context is one of multiple global crises, in the midst of which “our work for the elimination of nuclear weapons must be carried out in a much broader framework, taking into account the interface between nuclear and conventional weapons and militarism in general.”

One must also consider, he added, “the long-term humanitarian and environmental consequences of nuclear war, and the fundamental incompatibility of nuclear weapons with democracy, the rule of law and human well-being.”

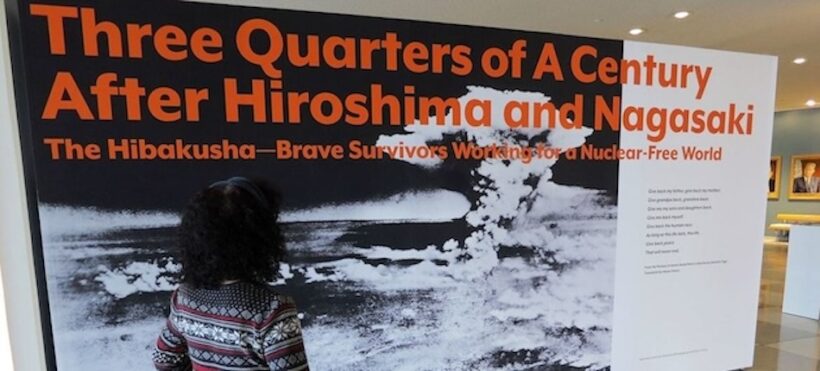

At an exhibition on disarmament at UN headquarters in New York, a visitor reads a text about a boy carrying his little brother to a cremation site in Nagasaki after the bombing of the Japanese city 79 years ago now. Image: Erico Platt / Unoda

“The glass is either half full or half empty, depending on how you look at it,” MV Ramana, Simons Chair in Disarmament, Global and Human Security at the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at the University of British Columbia, Canada, told IPS.

For the academic, “the fact that we have avoided a nuclear war since 1945 is also partly due to the persistence of the anti-nuclear movement. Historians such as Lawrence Wittner have pointed out the numerous cases in which governments have opted for nuclear restraint rather than unbridled expansion.”

Although South Africa is the only country to have dismantled its entire nuclear weapons programme, he noted that many other countries – Sweden, for example – have chosen not to develop nuclear weapons despite having the technical capacity to do so.

They did so in part, Ramana said, because of strong public opposition to nuclear weapons, which in turn is due to social movements supporting nuclear disarmament.

So, he argued, organizing for nuclear disarmament is not futile. Especially as we move into another era of great-power conflict, such moves will be critical to our survival.

You can read the English version of this article here.

According to the UN, a group of elderly hibakusha called the Nihon Hidankyo have dedicated their lives to achieving a non-proliferation treaty, which they hope will eventually lead to a total ban on nuclear weapons.

“On a crowded train on the Hakushima line, I fainted for a while, holding my eldest daughter, who was one year and six months old, in my arms. I came to my senses when she screamed and noticed that there was no one else on the train,” a 34-year-old woman who was just two kilometres from the epicentre of Hiroshima testified in a leaflet from the group.

Fleeing and searching for her relatives in Hesaka when she was 24, another woman recalls that “people were tumbling around, skin hanging off them. They fell with a crash and died one after another,” she adds: “Even now I often have nightmares about this, and people say: ‘It’s neurosis. ’”

A man who entered Hiroshima after the bomb fell recalled “that horrible scene; I cannot forget it even after many decades.”

A woman who was 25 at the time recounted: “When I came out, it was pitch black. Then it got brighter and brighter, and I could see burnt people crying and running around in total confusion. It was hell… I found my neighbour trapped under a fallen concrete wall… You could only see half of his face. He was burnt alive.”

The firm conviction of the Hidankyo remains unchanged: “Nuclear weapons are the absolute evil that cannot coexist with human beings. There is no other choice but to abolish them.”

At a Security Council meeting in March, UN Secretary-General António Guterres warned that with geopolitical tensions raising the risk of nuclear war to its highest point in decades, reducing and abolishing nuclear weapons is the only viable path to saving humanity.

“There is one way – and only one way – that will end this senseless and suicidal shadow once and for all. We need disarmament now,” he said.

He urged nuclear-weapon states to recommit to avoiding any use of a nuclear weapon, reaffirm the moratorium on nuclear testing and “urgently agree that none of them will be the first to use nuclear weapons.”

Guterres also called for reductions in the number of nuclear weapons led by the holders of the largest arsenals – the United States and Russia – to “find a way back to the negotiating table.”

He also urged Moscow and Washington to fully implement the New Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms, as provided for in the START Treaty, and to agree on a successor treaty.

“When each country pursues its own security without regard for others, we create a global insecurity that threatens us all,” the UN chief observed.

He lamented that almost eight decades after the incineration of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, “nuclear weapons continue to represent a clear danger to world peace and security, growing in power, range and stealth.”

“States that possess them are absent from the negotiating table, and some statements have raised the prospect of unleashing a nuclear hell – threats that we must all denounce clearly and forcefully,” Guterres said.

Furthermore, he argued, “emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and cyber and outer space domains, have created new risks.”

Guterres recalled that today, people are calling for an end to nuclear madness. They are calling for an end to nuclear madness, he said, from Pope Francis, who calls the possession of nuclear weapons “immoral”, to the hibakusha, the brave survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to Hollywood, where the award-winning film Oppenheimer brought to life the stark reality of nuclear doom for millions of people around the world.

“Humanity cannot survive an Oppenheimer sequel ,” he warned.

As Nagasaki marked the 78th anniversary of the U.S. atomic bombing of the city in August 2023, Mayor Shiro Suzuki urged world powers to abolish nuclear weapons, saying nuclear deterrence also increases the risks of nuclear war.

He called on the industrial powers of the Group of Seven (G7) rich countries to adopt a stand-alone document on nuclear disarmament that advocated using nuclear weapons as a deterrent.

“Now is the time to show courage and make the decision to break free from dependence on nuclear deterrence,” Suzuki said in his peace statement. “As long as states rely on nuclear deterrence, we will not be able to realize a world without nuclear weapons,” he added.

In his view, the nuclear threat from Russia has encouraged other nuclear states to accelerate their reliance on nuclear weapons or enhance their capabilities, further increasing the risk of nuclear war.

Suzuki, whose parents were hibakusha, or survivors of the Nagasaki attack, said that knowing the reality of the atomic bombings is the starting point for achieving a world without nuclear weapons. He said the testimonies of survivors are a real deterrent against the use of nuclear weapons.