Freedom of expression is a fundamental human right, enshrined in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. However, there are governments and individuals, including those in positions of power, around the world who threaten this right, from the UK to the US and as far south as Mileinato’s Argentina.

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought and expression, which includes the freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas, either orally, in writing, or through new information technologies, a right that may not be subject to prior censorship, but to subsequent responsibilities expressly established by law.

It is now 44 years since Unesco, meeting in Belgrade (capital of the then Yugoslavia), published the so-called McBride Report, also known as “Multiple Voices, One World”, which advocated the democratization of information after analyzing the inequality of communication in the world and proposing a new communication order to resolve these problems and promote peace and human development.

The report focused on the defense and protection of journalists who, because of their work, are often a thorn in the side of governments, politicians, and their economic interests, especially those involved in investigative journalism and war reporting.

But the protest media, journalists, and researchers know that our governments have never read the McBride report, and journalists and the press continue to be persecuted. Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, has been the victim of a sustained campaign of vilification and defamation since the leaks about the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq almost fourteen years ago.

He has been detained several times in high-security prisons in the UK and was granted asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy in London, where he was confined to two rooms without being able to leave from June 2012 until April 2019, when he was finally arrested again after losing his consular protection. Today, the world awaits the UK’s decision to extradite him to the US, where he is certain to be sentenced to death.

The US has been the only country in the world to legally retaliate against the information published by WikiLeaks, accusing its founder of 18 offenses related to espionage and computer crime. Assange faces 175 years in prison for these alleged crimes.

In 2022, The Guardian, The New York Times, Le Monde, El País, and Der Spiegel signed an open letter – “Publishing is not a crime” – to the US government asking it to halt Assange’s extradition.

To oppose Assange’s extradition is to defend freedom of expression, freedom of the press, and freedom of information. Because this case is a clear attempt to criminalize and intimidate journalists or media who dare to denounce the crimes of power. We cannot forget that more than sixty-five journalists have been killed by Israel in Gaza in recent months.

Nor can we forget that 780 journalists are imprisoned around the world and that the Spaniard Pablo Gonzalez has been detained for two years in Poland, a member of the European Union, without any evidence or charge.

The Dirty War against Mexico

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has demanded an apology from the US administration of Joe Biden, following press reports about the alleged delivery of drug money to his 2006 election campaign.

The White House and the US Department of Justice assured that there is no investigation against President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, referring to a piece of propaganda and political destabilization disguised as a report by the New York Times on the alleged financing of drug trafficking to collaborators of the president in his 2018 election campaign.

The idea is to plant false news, to plant suspicion, which is immediately amplified and viralised by companies dedicated to distorting democracy, such as troll centers. López Obrador branded the New York Times a “dirty rag” for “denouncing” him. “It is a disgrace, there is no doubt that this type of journalism is in open decline,” he said.

A month earlier, ProPublica published a similar “report” by two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Tim Golden, which quickly fell into disrepute for its lack of credibility and sources.

The trolls of the Mileinato

In Argentina, the far-right president Javier Milei is surrounded by an electronic machine that promotes and glorifies him, criticizes, insults, and defends his opponents, and harasses and threatens his critics.

Juan Pablo Carreira (Juan Doe on the Net) is the new director of digital communications for the Mileinato. He is known in the networks for his aggressive libertarian and far-right profile. The fish dies through the mouth: “If I ever get a peso from the state, I’ll be hung upside down in Congress,” he wrote on Twitter in 2015.

During the previous government, the National Cyber Security Directorate explained to the public that botnets are a series or network of computer devices capable of being connected to the Internet that carry out programmed tasks together, not always for legitimate purposes, i.e. they are malicious. They are set up without the knowledge that they include several devices (computers, mobile phones, tablets, etc.), are remotely controlled, and operate autonomously and automatically.

The name comes from “bot”, short for computer robot, and “net”, meaning network, and was first used in 2001 in a lawsuit brought by EarthLink Inc. against Khan C. Smith. As early as 2013, a researcher at enterprise security firm Proofpoint discovered a botnet that included smart TVs, refrigerators, and other “smart” appliances, which became known as the Internet of Things.

Today, this electronic machinery of the Mileinato includes militant and mercenary tweeters, influencers, troll, and bot farms, and anonymous operators who do the dirty work, such as launching smear campaigns, making phone calls, or sending emails, from the impunity of the shadows, to suggest that you shut up those who need to be shut up. He also controls “farms” of thousands of trolls, bot accounts, and other digital tools at Milei’s service.

The conservative newspaper La Nación points out that another indication of digital manipulation by bots and trolls is that Milei’s messages on Twitter, for example, show an inexplicable disparity in the number of ‘likes’ and ‘retweets’ that his messages receive within minutes of each other, while the interactions of some tweets are in the tens of thousands and those immediately following are almost nil.

Another indication of the presence of the defamation and advertising machine is the very high level of interference by accounts without photos of the users, or with fictitious names followed by several numbers, or that focus exclusively on retweeting and “liking” without generating any content of their own.

Once activated, the “bot” accounts usually remain dormant for three months or more, in a kind of lethargy or hibernation, before starting to disseminate multimedia material, because their creators have discovered that the algorithms of the social networks – especially Twitter – can block them automatically, according to La Nación, which refrains from giving specific examples to prevent the promotion of these same accounts.

In just two months, the ultra-right Milei government has decided to suspend national limits on the concentration of media ownership, to intervene in the public media system, promising its privatization, and to intervene in the power to apply the laws governing the sector, excluding parliamentary minorities from decisions.

Organizations representing community and self-managed media, social communication and journalistic professions, press workers, and human rights organizations asked the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to issue a warning about Argentina’s non-compliance with freedom of expression standards, denouncing greater media concentration and less freedom of expression.

The government announced the privatization of all state communication and information bodies (including the Télam agency, the television channel, and the national radio) and the closure of the National Institute against Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Racism. Milei himself promoted on social networks the celebration of the closure of a body designed to limit attacks on the human rights of minorities, which is so dear to libertarians.

In less than two months, Milei has also decided to repress journalists who try to cover demonstrations against austerity and the dismantling of the state.

The belief that the state should not impose limits on the private sector is leading the government to dismantle a media system organized into three sectors: private-commercial, non-profit civil society, and state/public. A system that was built after decades in which only private media owners had the conditions to carry out their activities, according to the Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales.

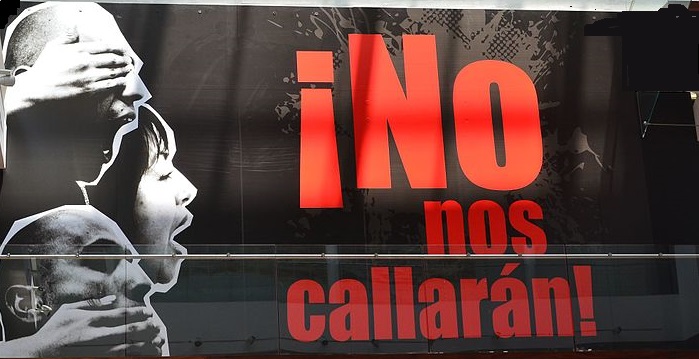

In addition to what has already been done, through the Decree of Urgency and Emergency (DNU) and the intervention decrees, the government – and the neo-liberal and ultra-right political groups that support it – are constantly threatening to abolish valuable policies that promote the right to communication, complemented by verbal and physical violence against press workers and the constant attack on journalists by the president and his officials.

Milei became president of Argentina with the cry ¡Viva la libertad, carajo! Today I dare to add: Long fucking live freedom of expression!