Traditionally, in the areas Christianised by successive empires, the legend of the Magi is celebrated on January 6th. The allegorical setting of the story is perfect. In a time and place crossed by caravans, wise men of Persian or Babylonian origin learned and knowledgeable in astronomical secrets, follow the course of a star from the East on camelback to venerate the birth of a child. A child who will be elevated to the mythical status of son of the god by preaching and sincere prayer, but also by habit and cultural forcing. The magicians (from the Persian ma-gu-u-sha, priest) do not come empty-handed. They bring gold, frankincense, and myrrh, as gifts for the newborn with attributes of majesty, divinity, and an antidote against pain and suffering.

In other latitudes, other times, calendars, and deities, people commemorated the birth of the sun or the Feast of Light on these days. In Egypt, the birth of the god Aion, the divinity that embodied the origin and end of time, was remembered with a torchlight procession. On the same date in ancient Greece, devotees of the god Dionysus celebrated his wonders.

For children in many places, however, the possibility of obtaining long-desired gifts matters far more than any liturgical significance. As is often the case, social morality has downplayed grandeur and generosity by associating that possibility with supposedly ‘good behavior’ on the part of children, and merchants – Pharisees of the temple in the Christian saga – also look forward to the date in the hope of making juicy sales.

But children born in Palestine have nothing to celebrate in these tragic times. They simply hope that no deadly bombs will fall from the sky and that perhaps, yes, some star from the firmament will illuminate the thoughts and feelings of the obsessed violent men who drop them, order them to be dropped, or manufacture them so that they will stop doing so.

Mendoza, the sixth day of 1938

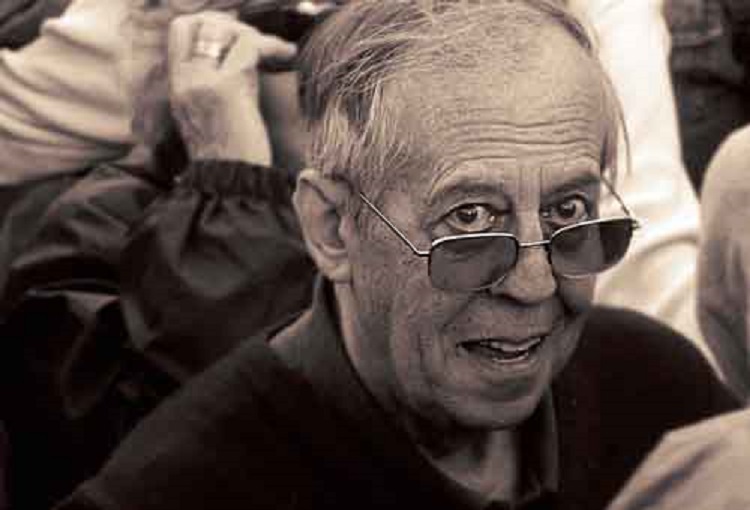

In a place far away from there, in distant South America, María Luisa Cobos, of Basque origin, gave birth to another child, her third son, on the 6th of January 1938. Mario Luis, as his parents decided to call him with a significant resemblance to his mother’s name, showed singular abilities from an early age. He was an outstanding gymnast, a brilliant student, and an avid reader, among other virtues. But it was not success that encouraged him, but the possibility of exploring beyond the then-narrow limits that the social milieu tried to impose on him.

Thus, as a young man, he began to propose experiments of various kinds, to organize groups and to investigate, with ever greater profundity, the essence and meaning of human existence. Along this path, he called his close friends to study and experiment to contribute to the development of human beings and the transformation of the world. And that small group expanded, reaching, through the permanent and determined action of those who adhered to his proposals, to all the ends of the planet.

Mario Luis Rodríguez Cobos had become Silo, the literary pseudonym he adopted and by which he is known today in different cultures around the world.

Silo’s contribution

In a note of our authorship in which we tried to highlight the revolutionary character of Silo’s work, we said:

“Although essentially existential, Silo’s teaching is necessarily transcendent. Thus, he invites us to rebel against the apparent inevitability of death, affirming the possibility of a destiny of immortality for the Human Being, suggesting a coherent life between what one thinks, feels, and does, overcoming indifference towards others, going actively and in solidarity with all.

Revolutionary are his proclamations in the social and political field, expressed in that motto which animates the humanist action in more than one hundred countries of the planet: “Nothing above the Human Being and no Human Being below another”.

Revolutionary is his conception of “the human”, far removed from all naturalism and zoologism, defining the Human Being as a “historical being whose mode of social action transforms his nature”.

His ideas in the area of psychology were revolutionary, basing human transformative capacities on the activity of his consciousness, the spatiality of its representation, and the broadening of the temporal horizon which is characteristic of it.

Revolutionary is his epistemological proposal, having developed a method that emphasizes the dynamic structural nature of all phenomena and the essential significance of including one’s look for a full understanding of what is being studied.

Revolutionary is his spiritual message, which rejects dogmatic imposition and religious intolerance to open up to the luminous experience present in the profundity of every human being. Spirituality promotes freedom of thought, and the search for good knowledge and, therefore, encourages freedom and diversity of interpretations about the sacred and immortality.

Revolutionaries are also his contributions to the field of mysticism, making available to any human being four initiatory disciplines in which he synthesizes inspiring experiences from various historical traditions.

Silo’s image of the future will be revolutionary, placing diverse cultures not only in a scenario of mutual tolerance but of convergence towards a Universal Human Nation, in which each one can contribute from its best historical accumulations”.

With much greater precision and knowledge, the Italian scholar Salvatore Puledda paid homage to Silo on the occasion of the Latin American Regional of Humanist Parties in Santiago de Chile in January 1999, in which he pointed out:

“Silo’s original contributions have not been limited to the field of psychology. Over the years Silo has produced pioneering work in the ambits of historiography, sociology, politics, and religion, which have touched on practically all fundamental aspects of human behavior. Through these works, Silo has been outlining a new conception of the human being and a universal political project, a new Utopia for the globalized world in which we already live and which he announced with unusual foresight”.

And something further on in that address:

“In this world that has lost the sense of the future, the sense of the project, that looks with anguish at the arrival of the new millennium, Silo will be proposing the Great Utopia for 2000: the creation of the Universal Human Nation that includes every one of the peoples of the planet on a parity level, but without destroying their cultural specificity. It will also be the Humanisation of the Earth, i.e. the progressive disappearance of physical pain and mental suffering thanks to scientific advances, a fairer and more egalitarian society that eliminates all forms of violence and discrimination, and the reconquest of the meaning of life. With this project aimed at humanity as a whole, Silo places himself among the great modern utopians, such as Giordano Bruno, Thomas More, Campanella, Owen, Fourier, and Marx himself. Here utopia – meaning a place that does not exist – represents an image, a project that guides and organizes the present and drags it into the future. It is a project launched to the new generations and which will have to find one of its driving forces here, in Latin America”.

Elaborating on Silo’s contributions to human thought and action, Puledda notes:

“I was saying that with his works, Silo has been building a new image of the human being as opposed to the image that is dominant today. And this is the same work that the first humanists of the Italian Renaissance, such as Pico della Mirandola, did. To fight against medieval Christianity, which placed Man in the dimension of sin and pain, and conceived him as a being who can do nothing but aspire to the forgiveness of a distant God, the first humanists proposed the image of a being conscious of his own dignity and freedom, who has faith in his capacity to transform the world and to build his own destiny.”

“For Silo, the human being is a historical and social being and the dimension that is most proper to him is not the biological but that of freedom. For Silo, human consciousness is not a passive reflection of the natural world, but an intentional activity, an incessant activity of interpretation and reconstruction of the natural and social world. Although he participates in the natural world when he possesses a body, the human being does not have a nature, a definite essence like all other natural beings: he is not only past, i.e. something given, constructed, finished. The human being is a future, a project of transformation of nature, of society, and himself. Against all determinism, against all dogma that freezes and blocks the development of humanity, Silo takes up this philosophical line which, through the central idea of human freedom, in the West goes from Pico della Mirandola to Sartre, revitalizes it, and transforms it into a cultural and political project: the Humanist Movement.

At this point, one might think that the religious dimension was foreign to Silo’s thought. The opposite is true: the search for the meaning of life, for transcendence as opposed to the absurdity of death, finds a central place in his work. However, like Buddha, Silo does not request anyone to believe in his ideas about the divine by faith, nor does he intend to propose a new religion with rites and dogmas.

He offers ways, experiences so that everyone can test for himself the veracity or usefulness of what he says…”.

To conclude that memorable intervention, Salvatore stated:

“It is because of all that has been said so far that I consider Silo a very special man, indeed, unique. I dare to say that in a culture such as Latin America, which has produced great revolutionaries, great writers, and great artists, Silo is the only thinker of global dimension.

And in a rhetorical sense, Puledda asks himself: “What is Silo like up close, for you, who have been his disciple, collaborator and friend for so long?

I must say that one of the aspects of Silo’s character that I most appreciate is his sense of humor, his ability to capture the comic or grotesque side of situations and people. A quality that unsettles those who approach him believing that a great thinker must be a frowning, distant, and boring person. Silo is capable of playing and laughing like a child, of continually marveling at the great human comedy.

But his is not distant laughter, the laughter of superiority concerning the infinite stupidities with which the lives of all men, great and small, are woven. This laughter is accompanied, like two sides of the same coin, by the patience and compassion with which he looks at the misery and the greatness of the human condition. Why Silo is, in my opinion, above all a good man. Goodness is for me his greatest quality. What else is there to say?

Only this. Lately, despite our long familiarity, the question has been coming to me more and more forcefully: who is Silo? So, to find an answer, I have followed the advice he gave me when I was looking for answers to important questions about my life. I launched the question into the depths of my consciousness and waited for the answer. Which was this: Silo is a guide, an initiate, someone who holds a key to open the door to the world of the spirit”.

That is why every January 6th has a special significance for the thousands of people who gather all over the world, especially in the Parks of Study and Reflection in different parts of the world to celebrate the birthday of Mario Luis Rodriguez Cobos, Silo. They do so because they consider his life and his message to be a great gift to humanity.