As had been anticipated, the new-old economy minister, Luis Caputo, unveiled a first package of measures that concretises the first step of the savage adjustment plan that was announced with the arrival of the ultra-liberal Javier Milei to the Argentine presidency.

Caputo, who had already held the post of finance minister and the presidency of the Central Bank during Mauricio Macri’s term in office, fired off the measures one by one in a pre-recorded message that was later retouched. The catalogue in question devalues the country’s currency, producing an immediate inflation rate of over 100% and aims, more or less, as in all previous neoliberal administrations, to shrink the state, favour the business of capital and comply with the foreign debt that the Argentine people neither acquired nor validated, much less enjoyed.

That is why the programme, merciless for the majority of Argentines, was hours after celebrated by Kristalina Georgieva, the current head of the International Monetary Fund, who in successive messages, after welcoming the plan “with satisfaction” pointed out that “After serious political setbacks in recent months, this new package provides a good basis for future discussions to put the existing IMF-supported programme back on track”.

To which is added, on the third day of the new government, the nationalisation of private debt of importers through the issuance of financial securities denominated with a clear ideological tinge (Bonos para la Reconstrucción de una Argentina Libre, BONPREAL) but whose substance chains the state to a new indebtedness. At the same time, cuts in the incomes of retirees and pensioners are being announced, and rumours are circulating about an unconscionable labour reform with a sharp reduction in rights, which would return the conditions of workers to something akin to wage servitude.

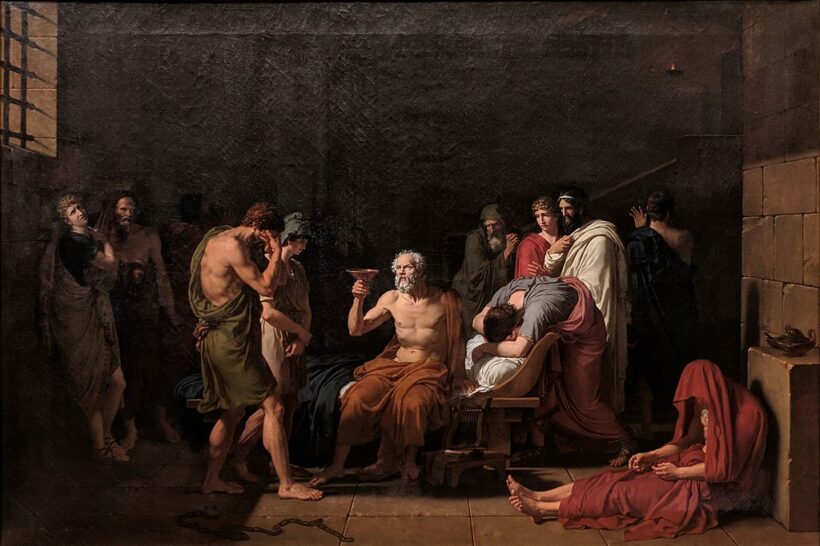

Thus, the worst assumptions are confirmed and new provisions along the same lines can be predicted. The “bad drink” announced by the new president in his inauguration speech thus becomes a very bitter pill to swallow, reminiscent of the lethal taste of hemlock.

The electoral suicide of the Argentine people

According to Plato’s Phaedo, Socrates drank the hemlock without flinching after being condemned to death for “corrupting the youth” and introducing religious ideas at odds with the gods of Athens.

The question that many are asking themselves at this point, inside and outside Argentina’s borders, is what drove the Argentine people to this kind of social suicide. Perhaps the complex socio-economic situation of almost half of the population prior to the election, the insidious anti-Kirchnerist propaganda spewed out by the hegemonic media over the last two decades, perhaps the wave of global political right-wingers or the emergence of a new generation devoid of any hope in current political practices are part of the answer.

But there may also be plausible hypotheses such as the attrition and lukewarmness of progressive proposals in the face of the aggressive and stentorian ultraright grotesques, the incessant action of less visible forces such as international banking or the (un)diplomatic agencies of the US government and its various tentacles, or the fanatical irrationalism of important groups immersed in the reverie of divine or magical solutions.

Perhaps the electoral outcome was influenced by a lack of knowledge of the basic strategy of the new rulers, concealed by the noise of attacks “against the class”, the stigma of alleged populist corruption or fantastic promises of “becoming a power again”, in the messianic style of the Trumpist slogan “make America great again”.

Perhaps many Milei voters harboured the secret hope that finally the new executive would not be able to implement drastic measures such as some of those unveiled, effectively believing that opponents had unleashed an exaggerated fear campaign. And surely, as has been the case in all elections, the proliferation of fake news and hate speech through segmented digital bubbles has played a key role.

Beyond all these analytical cuts, Wilhelm Reich’s question from his book “The Mass Psychology of Fascism” (1933) is worth asking: “Why have people for centuries put up with exploitation, humiliation, slavery, to the point of wanting them not only for others, but also for themselves? To which Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari add in their work “The Anti-Oedipus – Capitalism and Schizophrenia” (1972): “no, the masses were not deceived, they desired fascism at a certain moment, in certain circumstances, and this is what needs explaining, this perversion of gregarious desire…”.

Is it useful to cry over spilt milk, one might ask oneself, is it possible to mitigate the damage or prevent similar catastrophes in the future by analysing factors that are not rooted in the political conjuncture but in the innermost social structure? Could it be useful to avoid similar collective defeats elsewhere? We do not know, but it is certainly worth a try.

Maieutics for Argentines

Going back to Socrates, his technique -based on the Pythagorean idea of reminiscence- consisted of asking the interlocutor questions through which he gradually discovers issues that help him to arrive at knowledge. Socratic maieutics refers to the work of the midwife (μαιευτική in Greek, obstetrics), who helps to remove it to bring knowledge to light.

In this way, one could investigate what tendencies inhabit its interior, which made it possible for this conservative and ultra-capitalist vision to come to political power in the name of a hackneyed “freedom”.

First of all, it should be pointed out that the unrestricted acceptance of capitalism as the general framework of the economy and social life is by no means the exclusive patrimony of these libertarian currents, which only radicalise it.

In the mid-1950s in Argentina, “Every day a little drink, it stimulates and feels good” was a successful advertising slogan of a well-known brand of gin of Dutch origin. Nowadays, the popular drink seems to have been replaced by a daily dose of hemlock. Thus, it is that year after year, government after government, the people have been drinking the intoxicating influence of a system that privileges property as a source of power and supposed happiness.

Or how else would one accept the management of collective life by companies whose sole function is to increase profit? How else can one understand the efforts of a population that assimilates progress to consumption, that accepts a model of growth that entails significant environmental destruction, that allows monopolistic companies to manage their lives, that still believes that violence in any form can be solved with more violence? Undoubtedly, the collective disciplining indicated by the promoters of neoliberalism in the 1980s and revived in his discourse by Milei (“there is no alternative”, Thatcher said), has taken root in the collective sensibility in a way that is not easy to banish.

Something similar happens with transformative political action, which was a prime target of the civilian-ecclesiastical-military dictatorships that followed the Latin American revolutionary eruption in the second half of the twentieth century. The terror unleashed acted (and continues to act) on the consciousness as a threat of chastisement for those who aspire to profound changes. Those who are no longer here today and those who had to leave because of the bloody persecution were the first victims of the social intimidation synthesised in the ominous phrases “they must have done something” and “don’t interfere”, which permeated deeply into the subsequent psychosocial structure.

Added to all this are the various cracks that separate and divide a fractured society, making the realisation of joint mass projects difficult. These cracks are not those that on the surface are usually related to the antagonism of political colours, but are the result of historical development factors.

The social fracture is a product of the rupture of community ties, which have been severely damaged not only by the individualistic ideology sprayed daily on the various screens, but also by the ever-evolving changes in technology, which have introduced major transformations in the forms of production, communication and relationships.

There is also a strong cultural divide between the ” black heads ” and the ” blond heads ” in the Argentine population, which leads to discrimination and self-discrimination barely concealed by an illusory and never achieved homogenous Argentinian identity.

And there is also a tremendous generational rift, between those social segments that lived their golden age in the period of the development of heavy industry, of iron and concrete, and the cohorts that, born decades after, have grown up in environments of ecological reclamation and digitalisation. On both sides of this chasm, however, the same sense of destabilisation pervades. In the elderly, instability nestles in the disappearance of known parameters, in nostalgia for a vanished past, while the feeling of disorientation in the present and of an uncertain future is rife in the souls of the new generations. This unease, this shared insecurity, explains the complexity of the social mosaic of young and not-so-young people who supported the temporary triumph of libertarianism.

This instability also explains the unreasonableness of claiming a rigid social order and the retarded demand for values that have already expired. It is clear how the neo-fascist-libertarian variant fits in somehow like a plank of wood in the face of the shipwreck in which fear and uncertainty, loss of references and systemic asphyxia are mixed. And at the same time, why, in dizzying times, the hallucination of this horde is visualised as a radical and virulent possibility of change in contrast to the unattractive slowness and delayed effectiveness of the proposals for upward social mobility imported from the previous century.

Going deeper still, in the bedrock of Argentine culture there are traces of self-flagellation, the product of a Judeo-Christian landscape in which rigour, punishment for sinful behaviour and suffering are still valued and considered an inseparable part of existence.

In more recent tectonic layers of consciousness, it is possible to observe a growing deterioration of individual mental health, deepened by difficulties in bonding, increased loneliness and exacerbated by the isolations suffered in times of the coronavirus pandemic. Can one already speak of a collective mental health pandemic as a component of the painful rise of irrationalism in the political sphere?

Treading other paths

In an eschatological tone, Milei claimed in his inaugural speech that there will be “light at the end of the road”, while quoting the exterminator of indigenous peoples Julio Argentino Roca, he said that to achieve the “aggrandisement of peoples is only at the cost of supreme efforts and painful sacrifices”. A familiar formula that promises greater social suffering in the short term, postponing wellbeing and development for tomorrow in very unreliable hands.

But not everything looks so dark. It should be remembered that more than eleven and a half million people, 45% of the electorate, turned their backs on the far-right formula. People who, beyond the current situation, declared with their vote their willingness to defend the material and immaterial common heritage historically accumulated by the Argentine people and to resist the insensitivity of the insensitivity.

However, the construction of the future will have to include new ingredients and collective protagonisms that enrich this heritage. It will not be enough to repeat “we will come back” or “come back better”, nor will it be enough to believe that the post-neoliberal formulas of the first decade of the 21st century will be enough to nurture new utopias.

From this recognition of the need to update paradigms, slogans and forms of struggle, an intense debate with strong popular participation will have to take place in order to move, from the convergence of diversity, towards a new political and social stage for all the inhabitants of these lands.