The ineffective way of tackling crime Citizen security has become a state issue for democratic governments, and one that has historically been negatively evaluated by citizens, who also consider that the current administration, regardless of political colour, fails to deal with it adequately. The lack of a public security policy as a country, and not just plans of the government of the day, has led to an evaluation of almost zero effectiveness, given the absence of diagnoses, objectives, evaluations and systematisation, as Professor Hugo Frühling, Director of the Centre for Citizen Security Studies at the University of Chile, points out: “If there is no document with diagnoses, objectives, etc., there are no actors to assume commitments and others to ensure that these commitments are fulfilled”.

Thus, of the plans National Policy for Citizen Security (2004); National Public Security Strategy (2006-2010); Safe Chile Plan (2010-2014); National Plan for Public Security and Prevention of Violence and Crime; Security for All (2014-2017); National Agreement for Public Security (2018-2021) and the current National Plan for Public Security and Crime Prevention (2022-2024), all developed with public money, only a minimum percentage corresponding to the Quadrant Plan and the Neighbourhood in Peace Programme has been evaluated; There has never been an overall assessment of the programmes of the different administrations, nor of the effect of public policies, with abundant academic production on the subject, evaluations of processes rather than impact, and a low level of practical effect.

In this context, the mayors of La Reina and La Florida, José Manuel Palacios and Rodolfo Carter, have decreed a communal emergency in their municipalities at a time when citizens, authorities and the media are pointing to the greatest security crisis in the country, due to the survey of criminal acts registered in several municipalities in the Metropolitan Region. This measure, which bears no relation to existing statistical data, which show a drop in the commission of crimes from 2017 to 2023, aims mainly at increasing the budget, personnel, and equipment for the issue of public safety on a par with coercive measures as a mechanism to combat this problem in the country.

According to official statistics from the Centre for Crime Studies and Analysis (CEAD), Carabineros and the National Prosecutor’s Office, crimes of major social connotation (DMCS) registered a decrease between 2012 and 2022.

These crimes correspond to a group of offences that include violent robbery (robbery with violence, intimidation, and surprise), robbery with force (theft of a motor vehicle, theft of a vehicle accessory, robbery in an inhabited place, robbery in a non-inhabited place and other robberies with force), homicide, injuries, rape, and theft.

The increase in homicides over the last 10 years is due to the existence of organised crime, which places Chile, according to the average homicide rate in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) of 2.6 per 100,000 inhabitants, at 4.7, an increase of 67.8% in the rate of this crime, compared to 2012, when it was 2.8. This rate is a relevant element in the perception of citizen insecurity, as crimes are fewer, but with a higher number of murders.

These days, the Government’s Undersecretary for Crime Prevention released the results of the National Urban Survey on Citizen Security (ENUSC), which revealed that the perception of insecurity in Chile is 90.6%, the highest in 10 years. The measurement registers information collected in 2022, which shows an increase of 3% concerning 2021, which was 86.9%. For Alejandra Mohor, a researcher at the Centro de Estudios en Seguridad Ciudadana (CESC) of the University of Chile’s School of Government, there is a paradox in our country: “We have a historically low victimisation rate and, at the same time, a perception of insecurity that has remained high over the last 20 years. We have the highest incarceration rate in Latin America and the lowest crime rate.

Consequences of media editorial the perception of insecurity and the qualitative and quantitative increase in crime, i.e. violence, is directly related to the role of the visual and written media. The use of these issues as information is a significant constant that becomes more acute in times of political-social conjunctures in countries, with violence having more weight every day in radio, television, press, and internet programmes.

Under the false premise that they must report on everything that happens, these media resort to informative strategies selecting and privileging, among everything that happens, the criminal act over the non-violent, the exceptional over the normal, the incident over the process, the individual over the general, the immediate over the media, the secondary over the important, thus constructing a peculiar reality that is consumed by the great majority of the viewing public and which has a great influence on the public agenda of the governments in power.

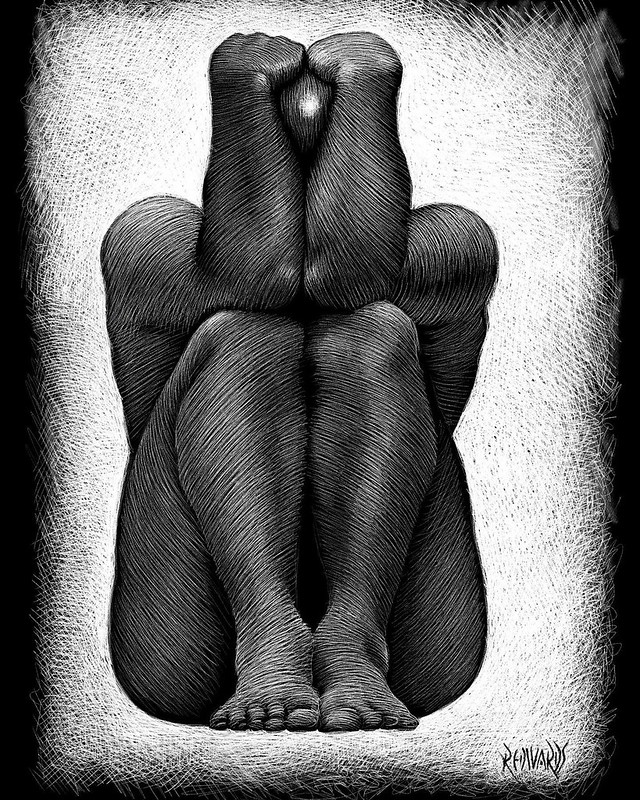

It is in this way that violent criminal acts are used as spectacle, as morbid entertainment, exposing themselves before the eyes of millions of people and thus covering up other social realities as complex as violence and which require urgent answers. Exposure to violence can lead to a distorted vision of social reality…., making true the well-known phrase “what is not in the media does not exist”. In this “produced reality”, a certain vision of violence and a specific social answer to it is intended, where the victim is exposed, the perpetrator is made invisible and a punitive penal solution is favoured, characterising a violent society. In this context, the sense of public security is currently based on the need to defend public order, risking the reinstatement of the nefarious policy of “internal enemies” in the country.

The installation of a state of exception from the right in the Metropolitan Region The arguments of the political class to justify the measures of “states of exception”, saying they want to deal with criminal activity and drug trafficking organisations through the use of the military in the streets, starting in Wallmapu 2021, 2022, 2023, and then replicating it in the northern regions of Chile, 2022, 2023, mark a logic (as we warned when they started) that allows today’s request to apply it in the Metropolitan Region.

We have already heard the voice of Governor Orrego of the DC, and now the right-wing mayors of La Florida and La Reina are lashing out with their media tactics, using language cunningly, despite the clear clarification of the Comptroller of the Republic that there is no legal support for their plan at the communal level… but, it is already being pumped all over the national press, and it has media reality.

The hypocritical arguments of the right-wing in power are maintained, denying the lifting of bank secrecy to follow the trail of dirty money, the corrupt, and using states of exception as a permanent measure, undermining civil rights. They place the Armed Forces in a function of “public order control”; without paying attention to the statements of generals who publicly clarify: “we do not use water cannons, nor rubber bullets; and when put in a situation we will not hesitate to use our firepower”, opening the door to situations that can produce an undesired escalation of armed violence.

Sacrificing civil rights to overcome fear of crime Fear of violence, amplified by the media, convinces ordinary citizens that they are obliged to lose their civil rights, accepting the exceptionality imposed by the state to have access to what should be the minimum standard, a peaceful daily life. On the other hand, the politicians in power in our country continue to endorse exceptionality as an answer, postponing the construction of a State that guarantees Human Rights, and strengthening the institutions provided for in democracy to resolve these situations of violence. The impossibility of acting effectively, as declared by the Public Prosecutor’s Office, and the abandonment of the promise to refound the police, are unacceptable, and it is not valid to replace these functions with military forces, generating in practice an increasingly police-like state.

Violence comes from above the discourse of the political and economic elite is not legitimate, given that violence in Chile is exercised from a model that they installed.

Violence starts from above, when political and religious leaders speak and demand, raising their voices. Criminal violence does not start from poverty or from the social inequality in which we live, but from the inhuman system itself, from the powerful who do not empathise with the principles of justice, of respect for human rights; they are the origin, they are the model of a violent society.

Alongside the attempt to make the anti-crime institutionalism work, a cultural change is needed to promote good treatment, a good tone, and direct and true communication, the only way in which we learn that what we do to others, we do to ourselves. “Treat others as you would wish them to treat you”. Violence ends with true gestures of reconciliation, aspiring for all of us to recognise that we are human beings and that we need to walk together towards a well-being built by all of us and for all of us.

Collaborators: M. Angélica Alvear Montecinos; Guillermo Garcés Parada; Sandra Arriola Oporto; Ricardo Lisboa Henríquez and César Anguita Sanhueza. Public Opinion Commission