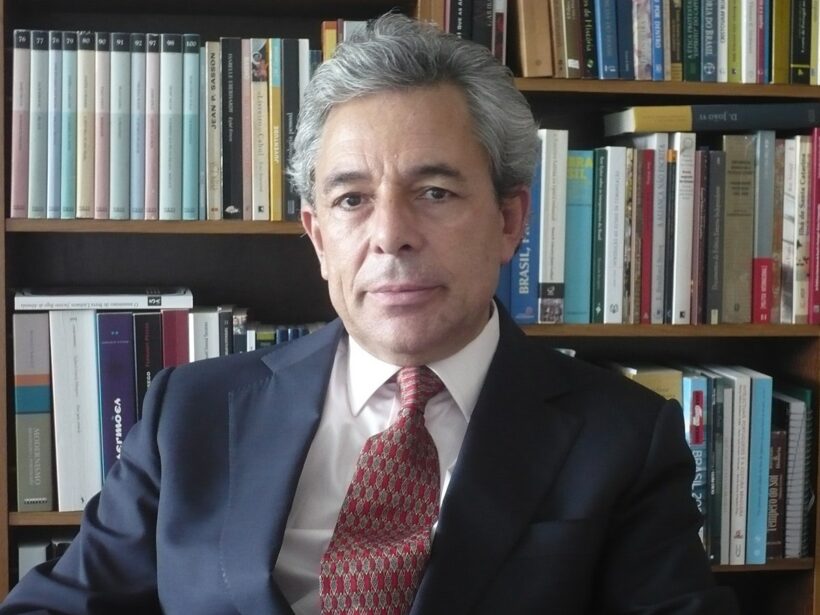

Carlos Fino (*) interviewed for PRESSENZA by Vasco Esteves

Carlos Fino was born in Portugal and was a radio and television reporter, war correspondent, news service presenter and press counsellor for four decades. He has travelled to Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Brazil. He has worked in Lisbon, Moscow, Brussels, Washington and Brasilia. He is perhaps the best known, Portuguese reporter in the world. He was an award-winning journalist, wrote books and has a doctorate in Communication Sciences. In 2022, he returned to Portugal to – as he himself says – “no longer be in the limelight of international politics and journalism and to lead a quieter life” with his wife, trying to live out his “aurea mediocritas” in the good old-fashioned way.

As soon as he arrived in Portugal in 2022, however, the Ukrainian war broke out, and he was deeply shocked by how it unfolded. He remained reluctant to intervene, but now he has decided to make an exception and give this exclusive interview to PRESSENZA about his experiences in Eastern Europe and the possible geopolitical conclusions that this experience will allow him to draw.

This first part of the interview covers Carlos Fino’s experiences in Moscow and during the collapse of the Soviet Union and the forced break-up of Yugoslavia. In the second part, to be published in a few days, he will talk about the current war in Ukraine, Eastern Europe in general, as well as ongoing deglobalisation and the emerging new world order.

Moscow

Pressenza:

Persecuted by the PIDE/DGS (secret police of the Salazar-Caetano regime), Carlos Fino found himself having to flee “a salto” (illegally) from Portugal to France in 1971. At the time, he was a student leader (he was a member of the board of the Academic Association of the Faculty of Law of the University of Lisbon in 1968/1969) and shortly afterwards joined the PCP (Portuguese Communist Party), which was still underground at the time. He was also a member of the MDP/CDE – Portuguese Democratic Movement – Democratic Electoral Commission, which contested the controlled “elections” of 1969, in defiance of the limitations imposed by the regime.

He then travelled on to Paris, and from there to Brussels, where he obtained United Nations refugee status and stayed for two years, working as a tram driver and studying law at ULB (“License en Droit de la Université Libre de Bruxelles”).

In 1973, via the PCP, he went to Russia to work as an announcer for Radio Moscow, which had a programme aimed at Portugal, where – along with Rádio Portugal Livre, based in Romania, and Rádio Voz da Liberdade, based in Algiers – it was picked up and followed clandestinely by the regime’s opponents.

Following the military coup of 25 April 1974, which overthrew the dictatorial regime of Salazar-Caetano, paving the way for the institutionalisation of a democratic regime, Carlos Fino returned to Portugal at the end of 1974, where he followed the ongoing Carnation Revolution and worked for a year as a translator for the Soviet news agency Novosti, which had just opened a branch in Lisbon.

At the end of 1975, he returned to Moscow, this time as a correspondent and reporter for EN (the Portuguese national broadcaster) and, later, for RTP (Rádio Televisão Portuguesa); this time he stayed in the Soviet capital until 1982, when he returned to Portugal following an attack on him by the Soviet police.

Between 1982 and 1989, he worked for RTP in Lisbon as a reporter, presenter and commentator. At the end of that year, he was appointed correspondent for Portuguese public television in Moscow, where he remained until 1995, when he was transferred to Brussels and, three years later, to Washington, always as RTP’s international correspondent.

Over the course of more than two decades (1973-1995), Carlos Fino therefore lived in Moscow three times, for a total of 12 years, following as a correspondent and reporter all the most important things that were happening in the Soviet Union, including its break-up and the emancipation of the Eastern European countries behind the so-called “Iron Curtain” … What did Moscow mean to you then, and what does it mean today?

Carlos Fino:

When I went to Moscow for the first time in November 1973, the idea I had of the Soviet capital, from what I read in the propaganda and in the ignorance of my green years, was that of a kind of red Brasilia – a developed city, open to the future, progressive, the seat of a power that on an international level was openly challenging the hegemony of the USA, whose role was then greatly tarnished by the Vietnam war.

Going to Russia to be an announcer for Radio Moscow – which I listened to clandestinely in Portugal – was for me the culmination of a personal evolution marked by contact with the poverty of the Alentejo, the struggle for 8-hour working days, which I witnessed as a child, and empathy for the humiliated and offended derived from the social doctrine of the Catholic Church, in particular the Second Vatican Council of 1961, when I was 13 years old.

This Catholic imprint ended up merging with communist influence when my parents left the Alentejo and moved to the Vila Franca region [near Lisbon] in order to give their children a higher education, since there was no university in the Alentejo at the time. The PCP was very strong and influential in Lisbon’s industrial belt and, even without being a militant, it was during those years that I became close to the party – both the labour wing and the intellectual sectors – and became involved in the democratic movement, its expression at legal and semi-legal level. Entering the Faculty of Law at the end of the 1960s strengthened this connection, which culminated in militancy while still underground.

Escaping from the PIDE [Secret Police] and crossing the border in 1971 consolidated this situation, but also marked a limit – pressured to become a party official, I said no: I wasn’t available to “wear the uniform”, in the words of Pires Jorge, the member of the central committee who tried to recruit me.

Even so, I agreed to go to Moscow at the end of 1973 for a job that was offered to me and that seemed attractive – to be a radio presenter – and also because the school year was coming to an end and the “lead” was in sight; it seemed like an attractive way out because it would fulfil a professional vocation that I already felt in me (apart from Radio Moscow, I also always listened to the BBC, Emissora Nacional and RTP, and I was charmed by the presenters) and because it would be an experience that could enrich me both humanly and professionally. All the more so because nothing yet predicted the 25th of April: on the contrary, the Opposition to the regime was disenchanted with the so-called “Marcelist Spring” and the regime seemed to be about to last.

Arriving in the Soviet capital was disappointing: instead of the red Brasilia I had imagined, Moscow was still a very heavy, politically oppressive, cold and uncomfortable city, where simply getting supplies was a headache, with very little on offer, in decaying, empty, smelly shops, where you had to queue to buy the essentials, everything or almost everything being of poor quality.

From then on, there was a whole period of reframing my own choices and as soon as 25 April came along a few months later, I immediately wanted to return to Portugal. After all, I had also contributed, albeit in a limited way, to that moment of liberation. Unfortunately, the party had my passport and understood that I would have to fulfil the contract – at least one year – so they didn’t give me the document, which prevented me from leaving. As a result, I wasn’t able to experience the joys of the early days of 25 April, or the historic 1 May that followed, as I had intended. That’s a bitterness I’ll take with me to the grave, and it’s also forever linked to my first experience in Moscow.

In the meantime, between April and November 74, I met Natacha, my first Russian wife, and my connection with Moscow, while losing its political militancy side, gained personal and professional relevance.

The year I spent in Portugal, between November 74 and November 75, was thus a transition – politically, I already had death in my soul, and now I wanted to return, not for ideology, but for love and my profession. I was going to create a fusion of Bécaud’s verses – Natalie – and the romantic music and ambience of the film Dr Jivago.

It was these two aspects that I realised in Moscow between ’74 and ’82, when – culminating an increasingly critical view of my chronicles – I was the target of an act of police brutality, typical of the Cold War, in an episode that marked my political break with a certain Russia.

When I returned in 1989 to accompany the culmination of Perestroika for the Portuguese public broadcaster, I did so to reinforce the two aspects with which I had left – profession and love – but now with a democratic political vision and no longer a communist one.

All this left me with contradictory feelings about my relationship with Russia, and Moscow in particular – disenchantment, frustration and discomfort, on the one hand, but also intense human relationships, personal involvement and a unique professional opportunity, a “mix” that would mark my entire career and even my life.

Today, I don’t miss Russia; Moscow is a page turned, but neither do I harbour any resentment and, in general, I don’t share the prevailing Russophobia.

From a distance, if the information is correct, Moscow (where I last visited in 2000, when Putin came to power) is now a much more palatable city than it was in the 70s – and even 90s – of the last century. And Russia is clearly trying to recover from the trauma of the fall of the USSR. On the other hand, I don’t think that European security can be built in confrontation with Moscow, but rather in negotiations where the concerns of both sides, in this and other areas, are taken into account and a mutually acceptable “modus vivendi” can be found.

As you said, in 1982 you were the target of a “typical Cold War act of police brutality” in Moscow. What exactly happened, and why?

At the time, I was already working for RDP – the successor to Emissora Nacional – and for RTP. In 1980, I had already covered the Olympic Games in Moscow. To understand what happened, you have to take the context into account. When I went to Moscow in 1975, following the 25 April Revolution in Portugal, there was a great curiosity about Eastern Europe and the USSR in particular. But there was also a moment – which continues to this day – of hostility towards the USSR: the USA had already boycotted the Olympic Games, and there were also other sanctions against the Soviet Union. We were in a Cold War context, and I was at the crossroads of these opposing tendencies (ideological, political, economic) and had to play a very big balancing act in order to be able to report from Moscow.

Although I was always very careful about what I said, my chronicles – following the movement of Soviet society itself – became increasingly critical. As a result, the communist press in Portugal began to openly criticise my work. On the other hand, there was also pressure from the Soviets: those in charge of the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs even said, rather amusingly, about foreign journalists accredited in Moscow that “those who aren’t spies are journalists”! I wasn’t a spy, but my chronicles – many of them based on information from the more open Soviet press itself, such as Literaturnaia Gazeta – tended to criticise the powers that be.

Then there was a police incident outside a hotel. I was already “under the microscope”, I think. I wanted to get in, they wouldn’t let me in, I raised my voice and there was some altercation with the security guard in front of the hotel. Suddenly, a plain-clothes guy came from inside the hotel and a group arrested me. I was forcibly pulled into a car and taken to the back of the hotel where the police station was monitoring what was going on in the hotel (it was an international hotel, and the station was full of cameras), and there I was brutally assaulted. I told them that my detention wasn’t right, that I wanted to talk to my embassy, and in that dispute, they kicked me hard between the legs and punched me in the liver and kidneys. I immediately vomited and was anaesthetised as a result of the severe pain I felt. It was only over the next 24 hours that the pain began to get stronger and stronger, until it became intolerable.

The Portuguese embassy protested, the newspapers in Portugal also reacted, the newspaper “Expresso” published an editorial about it, in short, the episode became a case of friction in relations between Portugal and the USSR. Through Portuguese diplomacy, I was referred to a doctor at the British embassy who observed me (there was no doctor at the Portuguese embassy) and, through him, who knew a doctor in Finland, I was then transferred to Helsinki, where I was hospitalised for about two weeks and treated with morphine!

I didn’t need an operation in the meantime because my body reacted naturally, but there were after-effects that remain to this day. After that incident, RTP called me back to Portugal, and I just went to Moscow to pack my bags and leave.

Carlos Fino (right) greets Mikhail Gorbachov in the Kremlin in November 1987. In the middle, the then President of the Portuguese Republic, Mário Soares (Photo by Wikimedia-Commons, Author: Luís Vasconcelos)

Carlos Fino (right) greets Mikhail Gorbachov in the Kremlin in November 1987. In the middle, the then President of the Portuguese Republic, Mário Soares (Photo by Wikimedia-Commons, Author: Luís Vasconcelos)

The collapse of the Soviet Union

Precisely at that time, in the late 1970s and early 1980s – I was already living in the Federal Republic of Germany at the time – here in Central Europe we were going through a phase of massive rearmament, not just in Federal Germany, through the Pershing II (intermediate-range nuclear missiles), all supposedly to counterbalance the Russian SS-20 missiles, which would be on the other side of the iron curtain. So, it was the high point of the Cold War. I remember that we were afraid of what would happen, that a nuclear war would break out – and we in Germany would be right there in the middle of the mess…

And on one of those days, I had a private conversation with a politician from the SPD (German Social Democratic Party) in which he told me that the West’s strategy was to arm itself more and more in order to force the Russians to invest more and more in sophisticated armaments, with the intention of destroying their economy and thus bringing about the collapse of the Soviet Union – which did indeed happen a few years later! This was therefore an intentional rearmament to put the squeeze on the Soviet Union, which they knew did not have the economic capacity to respond at the same level.

Do you think that the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 was really caused, or at least facilitated by the West, or rather the result of the weaknesses immanent in Soviet society?

I think it was already clear at the time that the system was unsustainable. Both economically and socially. But what your German interlocutor entrusted you with must also have contributed to deepening the crisis that was already taking place within the Soviet Union itself. In fact, the Soviet Union was like a giant holding up a very heavy bar, but unable to bear the weight. It was a “gaunt” giant that had grown in size with its victory in World War II, but the hyper-centralised system didn’t meet the needs of the economy and development. The crisis had been going on for some time, but it was obviously hastened or accentuated in the final phase by this military confrontation with the West, which also included, as you know, the Soviet adventure in Afghanistan, which began in the late 1970s and lasted throughout the 1980s, ending with the withdrawal of Soviet troops. And it was in this general context of crisis that disagreements arose within the Soviet Union’s Communist Party, with Gorbachev coming to power and trying to find a new path, perhaps more social-democratic, but still under the control of the CPSU. But Moscow eventually lost control of the situation… and this led to the end of the Soviet Union.

The war in Afghanistan in the 1980s was fuelled by the US, which incited and armed Islamist groups against Russia, including Osama Bin Laden’s future Al-Qaeda! This was a military siege by the other side of the globe against the Soviet Union, which also contributed to weakening it. In all this confusion, what was the role of Gorbachev – who was only in power for a short time – and his Perestroika, and what was the role of Yeltsin later on (when he took power in the 1990s)? Gorbachev tried to save socialism and the Soviet Union, but he didn’t succeed, and Yeltsin tried to get Russia on the right foot in capitalism, but he didn’t succeed either, because he couldn’t stop the rampant privatisation of his country… What did Carlos observe during his time there?

Gorbachev initially brought great hope in terms of freedom, of being able to breathe and speak, but he remained faithful to communist ideology to the end. He tried a few steps of change, but within that ideological circle. As a senior member of the KGB said at the time, Gorbachev, like Columbus, set out in search of India and ended up discovering America… But only Yeltsin truly broke with the communist regime, already in an environment of great chaos and the emergence of mafia groups, in which the supply system collapsed, prices rose, there were shortages of products and a sharp drop in the population’s standard of living. It hasn’t been missed.

Today, both are seen as the cause of the problems that followed, and there is no benign view of Gorbachev in Russia, let alone Yeltsin. He allowed the creation of oligarchs who took over large economic units at the price of rain, and the deception of the population that if they bought shares, they would benefit from it.

Here’s a quote from the American economist and professor Jeffrey D. Sachs from Columbia University: “In 1990-1991, I was an advisor to Mikhail Gorbachov and, during the period 1991-1994, to Boris Yeltsin and Leonid Kuchma, covering the last days of Perestroika and the first days of Russian and Ukrainian independence after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. I watched what was happening very closely. I saw that the United States was absolutely uninterested in helping Russia to stabilise itself.” Was that also your impression: the West wasn’t interested in helping Russia reorganise itself, but rather in taking as much of the cake as possible under the slogan “the winner takes all”?

I think that’s true. Geoffrey Sachs knows a lot more about this than I do, but that was also the feeling I gathered at the time. And that led to the great disenchantment of Russia’s reformist leaders: they didn’t find the support in the West that they thought they would. This includes Putin himself (from 2000), because in the 1990s there was still a rapprochement with NATO through the creation of a Russia-NATO Council that met in Paris, and Russia itself even asked to be integrated into NATO, which was openly rejected. Nobody ever really reached out for Russia to stand up. The West’s aim was not to reduce Russia from a world power to the weakest possible regional power.

That’s why Putin appeared on the scene in 2000. I remember Yeltsin passing the baton to Putin because the former no longer had control over the situation in the country. Putin took power in January 2000: what has changed since then, and has it been for the better or for the worse?

What has changed is the realisation by the Russian elites, or at least part of them – those most closely linked to the state, the intelligence services and the power structures – that the situation was unsustainable and that they would have to react. There is a factor of deep disenchantment with the support they had hoped to receive from the West.

Putin’s changes have been for the better, something like this was to be expected at a certain point in the championship, as they say. The decline in economic power and political influence, the contradictions that couldn’t be resolved, were untenable situations. Putin’s arrival in power, with a project to restore order and recover the economy, was therefore welcomed by the population in general; and even, initially, in the West, where it was rightly considered that it was necessary to bring order to the situation created by Yeltsin, to put an end to the highly dangerous chaos in a nuclear power. And Yeltsin also called Putin with the commitment not to investigate him and his clique, not to be disturbed. But then there was also a turning point in the West, when what analysts call a “unipolar era” emerged, in which the US began to take decisions in defiance of all the other countries in accordance with the motto “I want, I can and I do!”. At a certain point, Moscow reacted.

The forced break-up of Yugoslavia

And the high point of this reaction was the mid-air landing of Primakov’s plane (Russian Prime Minister from 1998-99). Primakow was on a plane on his way to the United States when he received the news that NATO was going to launch a military offensive against the former Yugoslavia and attack Belgrade; at that moment, he telephoned Al Gore (vice-president of the USA), with whom he was going to meet, in a last-ditch effort to try to prevent this attack, but Al Gore told him that there was nothing he could do, the die was cast. So, Primakov orders the pilot to return to Moscow, without even landing in the USA. This reversal of course by Primakov literally marked a turning point in what had been Russia’s foreign policy since the break-up of the USSR. It was a key moment whose consequences we are still experiencing today.

NATO bombs Serbia, further forcing the break-up of Yugoslavia, which was already underway in the 90s. Let’s talk about the former Yugoslavia, a very dramatic case, emblematic of what happened after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 90s. Although Yugoslavia was never actually part of the Soviet Union…

Yes, Yugoslavia itself was a kind of “mini-Soviet Union”, because within it different national sentiments existed and clashed with their contradictions, which were difficult to manage. Only a political figure like Tito could keep it together for so long. Since Western countries later began to encourage these nationalisms or internal regionalisms, Yugoslavia ended up falling apart. But the most decisive factor was the US’s unilateral decisions, without taking into account the interests of Russia, which has had a historical presence in the Balkans since the confrontations with the Ottoman Empire.

At the time, I remember that Germany – where I lived – was very keen to encourage the break-up of Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia, which was already a very small country, was broken up into several tiny, autonomous countries that had previously been mere provinces. Was this a form of “divide and rule”?

In 1999, NATO fought a war against Serbia, a part of the former Yugoslavia. It was a war conducted by NATO outside the decisions of the United Nations, with brutal bombing raids on Belgrade – the capital of Serbia – with the main aim of achieving independence for Kosovo (until then an integral part of Serbia), which NATO effectively achieved… The US then set up a military base in Kosovo, which is now the largest in Europe.

It’s true! And these attacks were even more brutal than what Putin is now doing in Ukraine, because NATO bombed Belgrade every day for almost 3 months, destroying public buildings, radio and television studios, ministries, hospitals and even the Chinese Embassy! The Americans’ speciality, incidentally, is bombing…

And it’s ironic to note that this separatism that the West fostered in Yugoslavia is in complete contrast to the anti-separatism that the same West and NATO are now defending in the war in Ukraine, where they want the Donbass and Crimea to return to the heart of Ukraine, even though these regions have their reasons for separating, or at least for gaining a degree of autonomy within Ukraine. These are two different measures for a similar situation.

Wasn’t NATO’s brutal attack on Serbia a first sign that the West was willing to do anything, even intervene militarily, to compete for a good share of the “cake” being offered to it in south-eastern Europe?

This was particularly shocking for Moscow, which historically has a special relationship with Serbia. There is always an aspect of Russian presence in the Balkans. And the fact that this war was launched against Russia’s interests and without consulting Moscow was the straw that broke the camel’s back. It was from then on, that Yeltsin lost his last illusions about the West. At the beginning of the transition, in the early 1990s, during the time of Russian foreign ministers like Kozyrev and Shevardnadze (the latter had been Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union and was later President of the Republic of Georgia), there was even a slogan similar to that of Mário Soares in Portugal with his “Europe with us!” after 25 April: in Russia, that slogan was “The West helps us!”. Afterwards, they realised that there was no such thing as aid or even dialogue, because the US simply gave and took, doing whatever interested or suited them.

From then on, Pandora’s box was opened: confrontation. If – the Kremlin argues – the US and the West can break up a country like Yugoslavia and create a country like Kosovo, why can’t Moscow also support the independence of Abkhazia or Ossetia from Georgia? From then on, there is a Russian policy of confronting Western policies and playing on the same board in the same way.

NATO’s war against Serbia in 1999 showed that, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was NATO that initiated military hostilities in Eastern Europe against Russia, and not Putin 23 years later with the invasion of Ukraine, as is often claimed in the West. This also shows that NATO has an expansive and aggressive character, and not just a defensive one, towards Eastern Europe. Do you agree with this statement?

I don’t know if I agree with this adjective that it has a substantially aggressive character “ab initio”, but that it started the war against Serbia is a fact. It was that moment – the unipolar moment in international politics that followed the break-up of the Soviet Union – that US option of “I want, I can and I command” and “we decide, without listening to anyone else” that ended up contributing to Russia’s change of attitude towards the West, of course!

[the second and final part of this interview is published here]

(*) Carlos Fino:

1948: Born in Lisbon, but lives and grows up in Alto-Alentejo (Portugal).

1967: Studies law in Lisbon, is a student leader and member of the PCP in the underground, and as such is persecuted by PIDE, the fascism’s political police.

1971: Crosses the border “by leap” (illegally) to Paris, then to Brussels, where he obtains United Nations refugee status.

1973: Moves to the Soviet Union, where he works as an announcer for Radio Moscow in Portugal and Portuguese-speaking Africa.

1974: At the end of the year, following the Carnation Revolution, he returns to Portugal and works for various newspapers and the former Emissora Nacional (EN).

1975: At the end of the year, he returns to Moscow, but this time as an international correspondent for EN and, later, for Rádio Televisão Portuguesa (RTP).

1982-1989: Works for RTP in Lisbon as a reporter, presenter and commentator.

1989-1995: Back in Moscow, covering as a journalist the break-up of the Soviet Union and the democratisation of Eastern Europe: Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, the GDR, Poland and Hungary, as well as the conflicts in Abkhazia, Georgia, Nagorno-Karabakh, Moldova, Chechnya and Afghanistan.

1995- 1998: RTP correspondent in Brussels.

1998-2000 – RTP correspondent in Washington.

2000-2004: Covers various wars and conflicts: Albania, Palestine, Afghanistan, and also the invasion of Iraq in 2003 by American troops, being the first reporter in the world to broadcast live images of the start of the American bombing of Baghdad.

2003: Publishes the book “A Guerra em Directo”, published by Verbo.

2004-2012: Works in diplomacy as Press Counsellor at the Portuguese Embassy in Brazil during President Lula da Silva’s first two terms in office.

2013: Retires and remains in Brazil.

2019: PhD in “Communication Sciences” from the University of Minho in Braga with a thesis that served as the basis for his new book “Portugal-Brazil: Roots of Strangeness” published in 2021.

2022: He returns to Portugal and “his” Alto Alentejo.

Throughout his career as a journalist, Carlos Fino has received numerous national and international awards and honours. He has around 37,000 followers on Facebook, a growing trend.

More information about the interviewee here: https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlos_Fino

All content produced by Pressenza is available free of charge under the Creative Commons 4.0 Licence.