The lucrative cocaine business is booming worldwide, after a contraction due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite the interesting positions of some of the countries in the region, Latin America has yet to seriously discuss its drug policy and abandon once and for all the prohibitionist and militarist recipes of the United States, the main consumer.

What has made this phenomenon so serious in our continent is social inequality, which is scandalous. For example, the peripheries are overpopulated by people who have no chance of getting jobs in the legal market and who see a way out in trafficking. Business? Big business: A tonne of cocaine fetches a thousand US dollars in Bolivia and sells for 35,000 in European ports.

The problems associated with drug production, trafficking and consumption in Latin America affect the quality of life of the population, are linked to forms of social exclusion and institutional weakness, generate greater insecurity and violence, and corrode governance in some countries, according to a recent report by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

In terms of production, Latin America accounts for the world’s total global production of coca leaf, cocaine base paste and cocaine hydrochloride. It also has a marijuana production that extends to different countries and areas, destined both for domestic consumption and export. Increasingly, it is also producing poppy, opium and heroin.

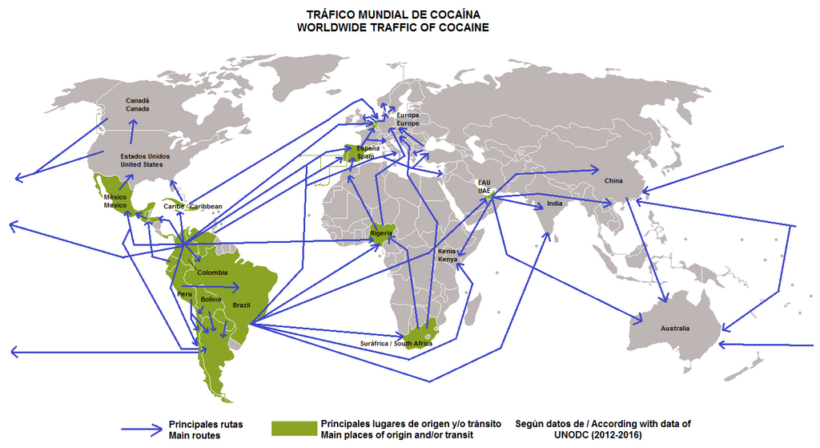

In terms of trafficking, the Caribbean area remains the most frequent route for drug trafficking to the United States, but the non-violent route via Central America has become relatively more important. Recently, river transport from coca-cocaine producing countries via Brazil has gained importance.

The problem of consumption mainly affects the youth population and males more than females. Marijuana, followed by cocaine base paste, crack and cocaine hydrochloride are the most widely consumed illicit drugs in the region, generating greater problems among young people with high social vulnerability, adds ECLAC.

Prohibitionism began more than 100 years ago as a way of controlling dangerous substances, often through militarisation, police, repression and prisons. Viewed in the big picture, the danger of the substances ends up being the militarised response to them, rather than the substances themselves.

This war under the US vision of the problem is not the way out for the region, which has been in this war for at least four decades and got nowhere, but a lot of money is spent (not invested). The beneficiaries of these policies are the arms industries and the “battalions” of drug trafficking workers who see it as a way of securing their livelihoods.

Today the criminals are much more articulate, they move through high society and, at the same time, attract poor people to do the dirty work because of their lack of economic prospects.

In South America there are two major drug trafficking routes. One is the southern route – Paraguay, central-southern Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay – which is important because it has larger urban centres and a larger airport and port structure, a logistical development that facilitates the transport of drugs, including a well-structured road network, which facilitates the export of cocaine to Europe, which is currently the big business.

The second is the Amazonian route, which leaves Peru and Colombia and heads towards the non-violent, following roads like the one that went from Ecuador to Costa Rica and from there to the Caribbean. It is a more US-oriented route.

Uruguay, which has some good laws to combat trafficking and money laundering, struggles to apply controls. In addition to the traditional domestic money laundering and drug transit services, there has been a growth in the domestic market and the refuge that fugitives from other parts of the world have been able to find in the country, often under the protection of corrupt rulers.

Uruguay has come to occupy an increasingly important position in the international distribution of the drug market. It is not a producer country, nor does it have a high demand, although it is one of the best in terms of per capita consumption: it is located in a strategic place for placing large shipments in Europe. And there are major weaknesses in the systems for monitoring and detecting illicit shipments.

In the large-scale consumption of information on the world of drugs, many things are taken for granted: criminal groups fight, corrupt or illegally deceive states that are always willing to confront them. However, outside of the great discursive hegemonies, even the name by which the phenomenon is known is under discussion.

The term drug trafficking derives from only two components of the activity: narcotics (which are a family of drugs, among others) and trafficking or transit (a link in a productive chain that also includes production, stockpiling, marketing, etc.). Although in terms of language there is no more than an example of metonymy in which the part (in this case, two parts) is taken for the whole, this composition is without…

Allan De Abreu, a Brazilian journalist with the magazine Piauí, who has been investigating organised crime for two decades. He points out that the caipira route began to be used in the 1970s for coffee smuggling. At that time, Brazil charged very high taxes on coffee exports and Paraguay’s taxes were negligible, so coffee growers smuggled it to Paraguay to export it from there.

And in the 1990s, when this business ceased to be interesting because of changes in taxation, the direction of the route was reversed and cocaine was taken from Paraguay to Brazil via the same route, trafficking centred in the cities of Punta Porá on the Brazilian side and Pedro Juan Caballero on the Paraguayan side, practically a single city. A large part of the cocaine that Paraguay receives from Bolivia and Peru passes through there to Brazil.

To dominate this region is to dominate the route. And the Brazilian cartel First Capital Command tried to control it, which led to a conflict with Pedro Jorge Rafaat, who was the big boss on that border, a story that culminated in Rafaat’s murder in 2016. The Paraguay River route, which runs down the Paraná and reaches the Río de la Plata, involving Uruguay, is also well established and has had many uses. Sebastián Marset is operating along this route, which culminates in the port of Montevideo, from where the cocaine leaves for Europe.

The Red Command – Brazil’s oldest criminal organisation – displaced local mafias from the Amazonian tri-border area and has taken control of cocaine production on the Peruvian side. The Amazonian triple frontier has become a disputed territory for several armed groups from Brazil, which have violently imposed themselves on the local Peruvian and Colombian mafias.

An investigation by Ojo Público reveals how this gang operates the Amazon river route, in alliance with Colombian criminal groups, and the recruitment of Peruvian riverside dwellers and indigenous Peruvians for drug production. This came in the midst of a war with Los Crías, a local faction from Tabatinga, which has allied with the powerful Brazilian First Capital Command to dispute territorial control.

But it is the Red Command that has managed to dominate – as it has done further south, on the border between Ucayali (Peru) and Acre (Brazil) – a large part of the routes in this Amazonian territory where not only drug trafficking, but also illegal logging and fishing predominate.

Meanwhile, the southern port of Montevideo, the Uruguayan capital on the Río de la Plata, offers drug traffickers the advantage of being a “counter-intuitive” exit point, due to its greater distance from the ports of arrival and the lack of control, as is the case in Paraguay, which has no control over what passes through the river.

Changes in the business

In this narco-business, there have been changes, the most notorious of which is that the gang leader has to distance himself from the drugs and that compartmentalisation is necessary. The first drug traffickers were personally involved in transport and thus always ran the risk of going to prison. With compartmentalisation, the lower levels of the gang do not know who they are working for and this protects the head of the scheme.

According to experts, the third change (or lesson learned over the years) is to be aware of the risk of verticalisation. For example, in the Medellín Cartel everything depended on Pablo Escobar and when he spilled out, everything fell apart.

The Brazilian PCC learned these lessons from history and today enjoys a horizontalised structure, organised in syntony: the syntony of ties (the lawyers), transport, finance, and communication (encryption of messages, which means that eavesdropping is a thing of the past). In the CCC, the head is the tuning, not the “capo” Marcos Willians Herbas Camacho (better known as Marcola), although nobody doubts that he is the big boss. But if he dies or spills out, the structure continues.

In Brazil, the PCC dominates and regulates crime in São Paulo and refrains from attracting the attention of the media and the police, while Rio is disputed by the militias, the Comando Vermelho and the Terceiro Comando Puro. The truth is that the PCC was born as a kind of prisoners’ union, after the massacre in the São Paulo prison of Carandiru, which left 111 prisoners dead. The prisoners then realised that they would have to unite against a corrupt state and a murderous police force.

The PCC was born in the prisons and spread from there: it is the fruit of mass incarceration, the result of this, of prisons overcrowded with small-scale traffickers, of absolutely inhumane health conditions. Does it make sense to arrest a micro-trafficker and imprison him so that he can leave with a postgraduate degree in crime?

With the new century, the CCC is heading west to establish itself on the Paraguayan and Bolivian borders, looking for cocaine suppliers to feed its outlets in São Paulo. After Rafaat’s death, they penetrated Paraguay and Bolivia, and today dominate the entire chain, from production in the Bolivian jungle to export.

To become a mafia, they only need to achieve consistent infiltration of the state. But unlike Pablo Escobar, the CCC has no political ambitions – at least for now – although it does have Italian mafia-style rituals.

What is striking is that the Brazilians imprisoned in Uruguayan jails who make up the PCC spread their ideology there, which is a strict set of rules. To join the PCC you have to be baptised and for that you have to have a godfather, which means that a member of the PCC will have to propose the candidate and take responsibility for his or her actions. It allows its members to have their own illicit businesses, but they can never fail to carry out the missions entrusted to them, nor divert money or weapons from the organisation. They have criminal courts.

But there is also a different, business model, that of Cabeça Branca, a large cocaine wholesaler that was above these organisations. It built an important logistical scheme in transit countries, such as Brazil and Uruguay. The wholesaler buys the cocaine and moves it to its point of exit: his power will be greater according to how many routes he has to make it.

Cabeça Branca, who remained unpunished for 30 years (the Federal Police did not even have a photo of him), had a fleet of planes, a fleet of trucks, officials in almost all Brazilian ports, ranches in Mato Grosso that served as warehouses for the cocaine that arrived by plane and from there continued by truck to the big centres.

The operation that led to his imprisonment was oriented towards a policy that did not focus on drug seizures, but rather on investigating money laundering and then seizing the criminal’s assets.

Ecuador has become one of the world’s largest exporters of drugs. The assassination of presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio is one of the predictable consequences of the new state of affairs.

The country has four geographical regions: coast, highlands, Amazon and Galapagos Islands. The coast is dominated by criminal gangs associated with drug trafficking. These gangs have moved into the highlands and the Amazon, but have not yet reached the control they exercise on the coastal strip. They transport drugs from the borders, which they then take to the high seas or remove it from the country in small planes. Their Mexican and European partners receive the drugs at sea, on airstrips in Central and North America or in European ports. In other words, Ecuador is a cog in the global machinery of drug production, transport and sale.

Before becoming one of the links in the trafficking, Ecuador was already a territory where drug money was laundered. The country uses US dollars as its national currency, which made it much easier to introduce dollars into the financial system and into all kinds of investments. Ecuador was laundering dollars before it became the main channel for cocaine outflows.

In recent years, the country’s modernisation has been dizzying. It has even been the case that private builders themselves finance the works being done for governments, such as municipalities and prefectures. There was money circulating discreetly to finance all kinds of enterprises, under conditions that would be incomprehensible if it were not for the fact that the money was not intended to make a profit, but simply to circulate. However, once a person had received money once, he or she could not refuse to receive it a second time.

Ecuador is geographically small compared to its neighbours: it has a quarter of the territory of Peru or Colombia. Over the last twenty years, central and sectional governments have built and improved highways, roads, airports and ports, making the country much more accessible than before. All this infrastructure has been exploited by criminal gangs.

Drug trafficking cases were not alien to the criminal history of the Republic. During the 1990s and at the beginning of the millennium, local drug traffickers were arrested and prosecuted, but they were still small examples of what drug trafficking was all about. Even so, the murder of Congressman Jaime Hurtado in the late 1990s was linked to his investigations into money laundering in the financial system in those years.

The current system of things, the unprecedented power that criminal gangs have come to have, was established over the last twenty years. Allegations of complicity between politicians and drug traffickers in Ecuador became increasingly common. Clandestine airstrips and docks were set up in collaboration with politicians in the coastal region. One incident gives us an idea of the penetration of the state apparatus by drug traffickers: in 2013, a diplomatic pouch full of drugs was sent to Italy. The scandal ended up affecting the foreign ministry and showed what kind of relations had been established between drug traffickers and politicians.

The non-violent coexistence between narcos and politics ended with the coming to power of Lenin Moreno in 2017, when he completely broke with his revolutionary past and dedicated himself to pursuing the corruption of his former coidees: Jorge Glas, his vice-president, was investigated, tried and convicted for corruption. Among other cases, Glas was accused of receiving bribes from the Brazilian company Odebrecht. Right now, the Brazilian justice system has just withdrawn the cases against Glas.

Moreno and his successor, Guillermo Lasso, broke alliances with Russia and cooled their relationship with China. Moreno handed over Julian Assange and in a very short time the United States regained a former ally in the region. The ground was thus prepared for the war on drugs, in which the United States is the country’s main ally. The war against drugs began with Moreno and has continued with Lasso. This war means millions of dollars and huge amounts of arms for the police and the army.

As everyone knows, the war on drugs with US “technology” and “intelligence” has not worked in Colombia or Mexico. Why would it work in Ecuador?

A few months ago the US ambassador in Quito accused several police generals of collaborating with drug traffickers. The US embassy withdrew the generals’ visas, but the government of Guillermo Lasso did not separate them, nor did it investigate or prosecute them. It did nothing: why can’t anyone confront the police? It’s a question that unfolds into another: why can’t anyone confront the narcos?

The accusation that Ecuador is governed by a narco-state takes on full validity in the face of the murder of Fernando Villavicencio. It turns out that those who are supposed to control crime actually collaborate with it. Not only do criminal gangs already totally control cities like Daule, where they tried to assassinate the mayor, and others like Manta, where they effectively killed him last July. Two cities on the coast.

There is still no clear reason why Fernando Villavicencio was murdered. The journalist and politician was determined to denounce cases of corruption during the years of the Revolution. And during the last few weeks he confronted the criminal gangs: he even held a political rally in one of the cities that are the cradle of these gangs. Villavicencio’s relatives and comrades say that the police were negligent in the protection they were supposed to give him.

At the time he was killed it was uncertain whether he would be able to make it to a second round. His murder has spread terror in the capital and deepened the feeling that there is no way to stop narco violence against the state and society.

Pablo Cuvi, editorialist of the portal Primicias, is already openly talking about legalising some drugs. The basic problem is that the mafias do not want to go legal, because they would have to pay for the crimes related to drug trafficking and because it is more profitable for them to keep the business clandestine. As Clausewitz said, war is a continuation of politics: for many actors, it is preferable to keep the war going, so that they can gain power that they could not conquer through politics.

Who, then, is responsible and guilty for the murder of Fernando Villavicencio? It should be borne in mind that criminal gangs have links with the correísmo and even with the current government: the recent discovery of links between Albanian drug traffickers and high-ranking government officials in charge of public procurement is a recent development. The murder of Rubén Chérrez, a friend and adviser to Lasso’s brother-in-law, points in this direction.

Verónica Sarauz, widow of Fernando Villavicencio, has pointed the finger at Correísmo and the government as responsible, although she lacks the evidence for it to make such a claim. Lasso came out practically unscathed from the investigation against him for being one of the protagonists of the bank holiday, that is, for the collapse of the financial system that meant the loss of savings for hundreds of thousands of bank customers.

The police did not guard Villavicencio as they should have and one of the gunmen they were supposed to take to hospital died in the hands of the police: instead, they took him to a police station. In other words, politicians and assassins acted in full view of the forces of law and order, who let them act. It is like what happens in the film Z, by Costa Gavras.

Finally, we must ask ourselves if Fernando Villavicencio was a CIA agent, as former president Rafael Correa claimed, and as Telesur revealed. If such a thing were to be proven one day, it would not only be local politicians, but also the governments of the region and even that power that is waging war in Europe, who would be behind his assassination