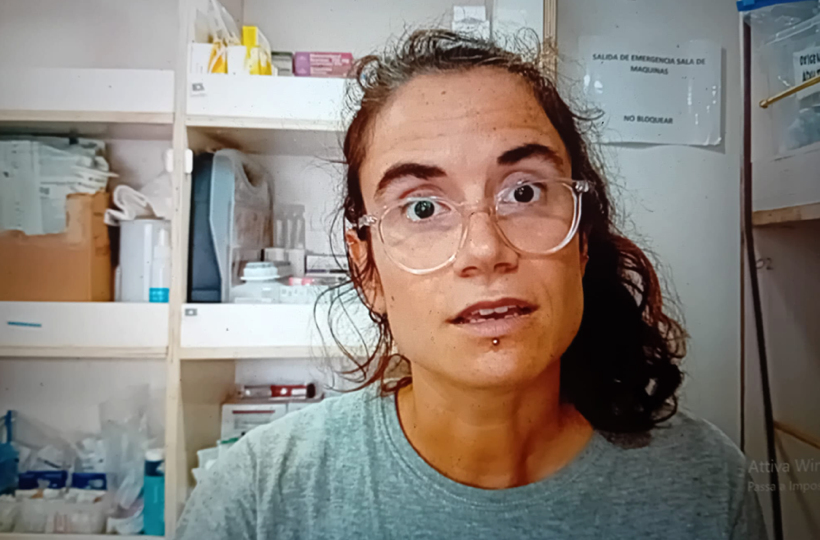

Finally, I managed to get on the Open Arms, after the misadventures of the day before. I first meet the captain and then have a long chat with the nurse who is in her med-box taking inventory. We sit down and she gladly tells me [how things are].

My name is Laura Lopez, I come from Valencia and I am a nurse. I have worked several years as a nurse in various situations around the world, including Syria. I have been part of the Open Arms work team for four months.

How many “rescues” have you made in these four months?

An average of two or three for each campaign that lasts three weeks, then there are other small interventions in which we give life jackets, or report situations to the competent authorities.

Was the reality as you imagined before boarding?

I would say yes. However, I can say that I was lucky, the people we recovered in the middle of the Mediterranean hadn’t been at sea for many days, so we didn’t find any difficult situations of hypothermia or dehydration.

Do you detect more physical or psychological disorders?

I would say both, from a physical point of view because the spaces here are limited and it is not easy to sleep comfortably stretched out on the deck of the boat; even the moment of distributing food is not easy, but there are also many initial difficulties in relating to each other, there is no doubt that we come from “another world”, with all our privileges. A doctor works with me and we also have the possibility to easily contact three people online; they help us from a psychological point of view. Sometimes we as a team need it!

You are two women in this case, maybe it’s better this way?

Surely to assist the women who get on board – who have sometimes suffered sexual violence, or have small children – it is better for a woman to approach them. For example, we were able to give some women an ultrasound with the machine we had on board.

How do you see the children? Do they seem aware of the situation they are experiencing? Maybe the traumas will come out later?

The children, always in my short experience, seemed to me to be well aware, even in the way they play (in which perhaps there is a policeman chasing…). The little ones are well pampered by many adults, including us. Sure, maybe the traumas will come out later, who knows.

Where did the migrants you rescued come from?

Especially from Eritrea, even if the boats came from Libya. Here the experiences, at least the ones they were willing to tell us about, were decidedly traumatic.

What language do you communicate in?

In what we can, English, French, Portuguese, we have a cultural mediator who helps us with Arabic, but the main challenge was with Tigrinya. (Translator’s note: Tigrinya is an Ethio-Semitic language spoken in Eritrea and in Northern Ethiopia).

Have you seen dead people these [past] months?

In these 4 months no, but in the past yes. Management is not easy, the bodies are loaded on board, they are kept in a particular area, but we certainly don’t have a suitable and cold space here. We ask that the bodies be evacuated as soon as possible.

And if there is a seriously ill person, how do you evacuate him/her?

A helicopter comes, a person drops down to tie up the sick person and together they go up quickly. It’s not an easy procedure, especially if the weather is bad. Another time, with our fast “launch”, we left him/her in Lampedusa.

How do you handle anger, both from saved people and your own?

It is a constant, frequent management, it is part of everyday life. Frustrations are around the corner; we have three psychologists that we can contact by video call whenever we need them. They are very useful. Luckily the connection is good, at least on the bridge.

And what about vomiting?

Yes, it’s not easy, but we are quite prepared to handle situations. I myself am in the process of getting used to the sea and it is costing me an effort. The process is gradual, those who have been at sea for a long time are much more used to it and no longer suffer.

Do you think that if someone gets seasick it’s best that they avoid doing what you do?

I think it is much more difficult to get used to the human situation in which we find ourselves. Dealing with very harsh realities, with which you usually don’t come into contact, is much more complicated than coping with seasickness. And above all never being able to disconnect, one is always here, at the service, and there is little space to disconnect, scream, vent anger or cry. We cannot collapse.

On the news you often see policemen using gloves on the migrants who have just got off, of course you can imagine the reason for these gloves, but also the unpleasant sensation of being touched by the plastic: how do you do it?

We try to avoid it, if possible, especially those complete protection suits that are very “stigmatizing”, it is still a matter of making sure that the contact is as human as possible. If I’m taking a person’s pressure and our skin are healthy, it’s absurd to wear gloves, it doesn’t make sense and it would be an extra barrier.

When you greet [the rescued people], do you hug or not?

Yes! [we do]. Not when they get on the boat, at the beginning when their data is taken, but when they disembark, after days spent together, yes. In the end, yes, there are emotions, laughter, tears…

How do you feel about what they expect from Europe?

For them, arrival means above all safety, but I perceived a “dangerous” optimism, for example a boy from Bangladesh said to me: “It’s good that we are getting to Italy where all the people are good!” Maybe because he came from Libya where all people, according to him, were bad. We try to prepare them, restoring reality somewhat, [by saying that] there are good and bad people everywhere: so that they know that they will not be welcomed by everyone.

Have you seen signs of torture on their bodies?

I don’t know if it was torture exactly, sure we saw many wounds, cut marks, and skin diseases due to the terrible hygienic situations they experienced in Libya.

How are your stories received from friends, relatives, etc. who are on dry land?

There really is everything: [It goes from] those who see these things on the news, who see the war in Syria and get used to everything, without paying much attention to it, up to people who, on the contrary, are struck by the message, understand, and get active.

How did you experience the announcement they gave you: “20 days of stoppage here in Marina di Carrara!”?

Even if it was a bit of a “chronicle of a death foretold”, it was a heavy blow, a powerful frustration.

If you had the president [of the Council of the MInisters, i.e. the Prime Minister] of the Italian government in front of you right now, what would you say to her?

I would ask her that she be] humane, that she try to be more realistic and empathic with realities that are not like hers. And that there are very positive effects of migrations, and this is scientifically proven. In short, it opens the doors.