The situation that has affected Jehovah’s Witnesses in Eritrea for 30 years certainly deserves greater media coverage. The Eritrean government has in fact undertaken, unfortunately for decades now, the sad practice of imprisoning many faithful, including women and elderly people, and subjecting them to a detention regime that does not provide the slightest respect for inalienable human rights. All because of their religious beliefs.

Way back in 1994, the newly elected President Isaias Afewerki (still in office today) made military service mandatory and began this harsh repression by denying Jehovah’s Witnesses the right to make use of conscientious objection, as an alternative to military conscription, despite the fact that for several decades the Witnesses had carried out this service with commitment and had over time obtained various certificates of thanks for their work. With the presidential decree of October 25, 1994, the Witnesses were deprived of citizenship due to their abstention from voting and their conscientious objection to military service. Since then the security forces have begun to imprison, mistreat and even torture not only young Jehovah’s Witnesses of military age, but also women and the elderly, triggering a true religious persecution with the much broader objective of forcing them to renounce to their faith.

From 1994 to today, at least 243 Jehovah’s Witnesses have been imprisoned in Eritrea. On average these people spend between five and twenty-six years in prison because of their faith. Unfortunately during these periods they are forced to suffer inhuman prison sentences which in some cases even led to death: it was sadly made known that at least four of them died while in prison, while three died after their release due to the harsh conditions they had to endure during detention.

All this continues to happen despite repeated appeals from international bodies for the respect of human rights which urge a change of pace in this regard. In 2016, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea submitted a report to the United Nations Human Rights Council in which it stated that with the “persecution on both religious and ethnic grounds” of Jehovah’s Witnesses and others, the Eritrean authorities have committed a “crime against humanity”. In 2017, the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child expressed grave concerns about the mistreatment of children of Witnesses, calling for Eritrea to “recognise and fully implement a child’s Freedom of Thought, Conscience and Religion with no discrimination.”

In May 2019, the UN Human Rights Committee urged Eritrea to release those arrested for exercising their right to freedom of religion and also requested that Eritrea “ensure the legal recognition of conscientious objection to military service and provide for alternative service of a civilian nature for conscientious objectors”. Subsequently, other appeals followed, which to date have unfortunately remained unheard. In fact, today’s reality still tells us that the Witnesses in Eritrea are forced to undergo prison sentences of indefinite duration, which in some cases can even last for life. Unfortunately, in the country there are no viable legal venues or remedies in their favor and this means that their conviction is equivalent to a perpetual prison sentence.

Three emblematic cases

Three stories that can summarize what Jehovah’s Witnesses experience in Eritrea are those of Negede Teklemariam, Paulos Eyasu, and Isaac Mogos. They were arrested on 17 September 1994, when they were only 21, 22 and 19 years old, due to their conscientious objection to military service and detained without any formal charge, trial, or conviction, for 26 years.

In a recent interview, Negede said that in recent years he has been imprisoned in the Sawa military camp, where prisoners are kept tied with ropes, in a state of severe malnutrition, subjected to severe beatings and forced to work at the limit of their strength. “There was never a hope of one day being released, let alone even going to face a court that would sentence us. They were just waiting for us to go insane or to die due to lack of medical treatment,” the man said.

Negede then continued:

“The soldiers took me to the wilderness and told me to dig a hole. […] They said ‘we have tried many things on you, but you didn’t change. […] They put me in the hole. The hole was deep enough for only my neck to be above ground. Not only was the strong daytime sun beating on my head. I am buried in sand that the sun has been beating on all day. I was sweating and slowly starting to pass out. There was a car with military personnel travelling from a distance. They could see a body buried with only his neck above the ground. The soldier was not from the military camp. He was simply passing by. He was a high-ranking military official. I didn’t know him personally. He didn’t know me. He asked the men: ‘How did this even happen? Is that even allowed to do this to a human being?”

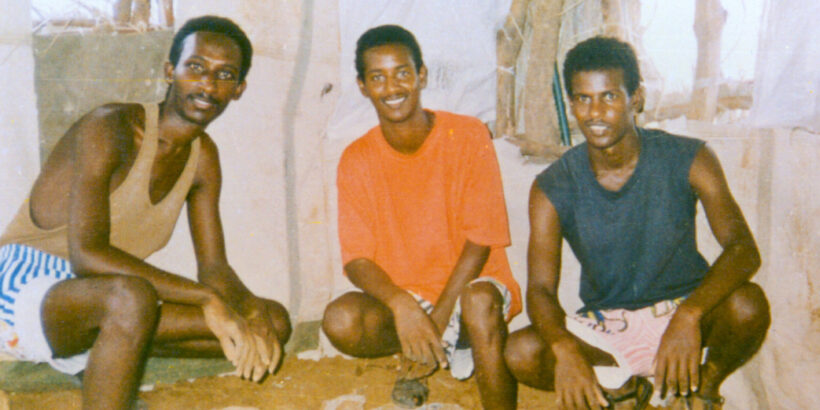

The three boys were also at the center of a particularly significant episode. Some members of the prison staff took a photo of these three boys with the intention of telling their story to the world and telling their families how their loved ones were doing. In the photo (visible on the cover of this article and published on the jw.org website) the three boys appear smiling and Negede, after many years, explained that smile like this:

“We didn’t want our family members or our parents who saw the picture to see us sad and dejected.”

He then explained that all these years he and the other Witnesses in prison have drawn the strength to endure these hardships from their strong faith and the unique power of prayer.

In December 2020, after spending more than a quarter of a century behind bars, Negede, Isaac, and Paulos were released, along with 23 other Jehovah’s Witnesses who spent between 5 and 19 years in prison. Currently, 32 Jehovah’s Witnesses (22 men and 10 women, aged between 24 and 81) are still in prison in Eritrea because of their faith. Today it is more desirable than ever that similar situations cease and that the inalienable rights of any person are respected, regardless of their religious faith.