It is catharsis and art to paint forgiveness, to carve it in stone or cast it in metal; but more difficult than sculpting marble is to carve the spirit and, after a tragedy, to dedicate oneself to work for the victims and for non-violence.

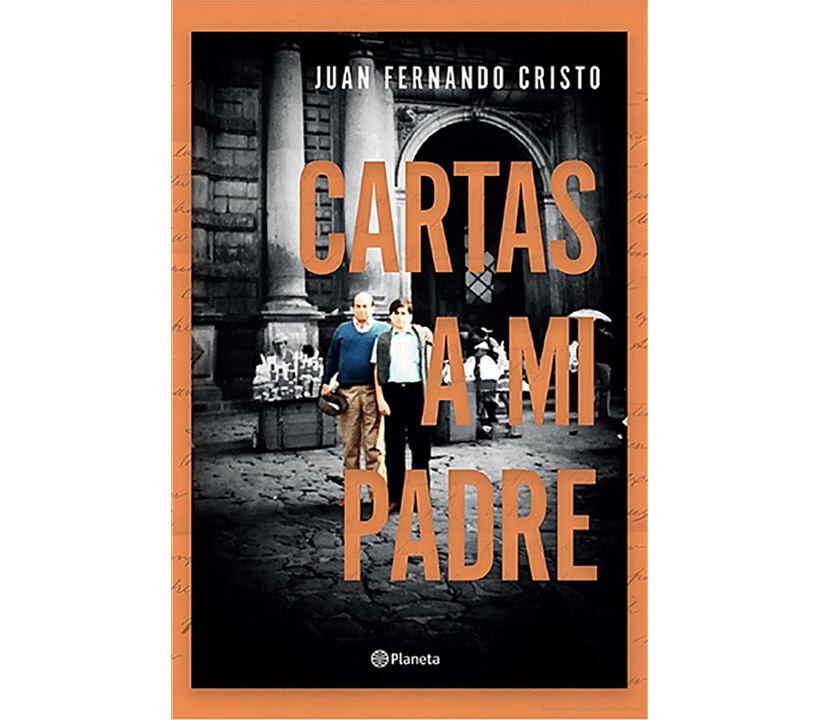

Last week Piedad Bonnett – the writer-poet who has told us with strength and gentleness the saddest sorrows and the deepest pain – presented Juan Fernando Cristo’s book Cartas a mi padre (Letters to my father) at the Gimnasio Moderno bookshop.

It is a context and a compilation of the 25 letters that year after year – since 7 August 1998, 12 months after the assassination – Juan Fernando wrote to his father. 25 letters published in the newspaper La Opinión de Cúcuta, and one feels – one knows – that “from the place of death” the doctor and politician Jorge Cristo Sahium has received them all, one by one.

According to the ELN, this crime was a mistake. Of course: taking someone’s life will always be a mistake – after more than 60 years of armed conflict, how will we not know! But the most urgent thing to admit and make amends for is that violence is a mistake that does not only happen in the hands of the person who pulls the trigger. It involves the hands and words, the actions and the lack of love of all of us who have caused wounds. Violence is a mistake that we have to heal from. We cannot go on escalating orphans, big and daily wars, the ones that are fought in the mountains and on street corners, in classrooms and in squares, in bars and altars. We have to heal ourselves, until we understand that we lack schools for children and we are overwhelmed, overwhelmed, by the fact that schools for hired assassins are spreading like wildfire.

The greatness of Juan Fernando Cristo – who was a senator, diplomat, minister, creator of the Victims’ Law – lies in the decision he took 25 years ago to sublimate the pain of his father’s death and dedicate himself from the public sphere to building and defending peace policies. Instead of having delivered himself to revenge – not even to the elusive and just search for justice – Juan Fernando dedicated himself to working for a peaceful Colombia. Nothing will take away the void, but it would be a relief to know the truth. Let’s hope he succeeds. He deserves it.

Juan Fernando Cristo. Photo by gloria Arias Nieto

Piedad made a beautiful presentation. She led, from the poetry that is her life, a dialogue of good human beings, a dialogue in which it was made explicit that pain can be not a sentence but an engine, a redemption and not an end point.

Juan Fernando was precise, generous and genuine. He was clear in saying that requesting forgiveness without saying why and who was responsible is an incomplete request. It is not possible to forgive completely without having someone to look in the eyes of and hear the truth of an “I did it”. Who is forgiven when the aggressor has no face, no pulse, no voice? He hopes, one day, to know who killed his father. It is not enough for him to know that it was a mistake, it is not enough for him to miss every day that father who taught him by example to serve in public, that grandfather who did not see his grandchildren grow up and that doctor who did not have time to found more hospitals and relieve more lives, because his own was taken away from him.

The book leaves one with a lump in one’s throat, but, somehow, also with a glimmer of hope. From the prologue of this being of light that is Ricardo Silva, “this logbook of grief (…) about the loyalty of a son to his murdered father”, everything is a testimony of love, a mission. “This book is a broken heart,” Ricardo says. Yes… and it is a plank of salvation, a rescue of ourselves, so that the stupid temptation of rancour does not cross our minds.