By Maxine Lowy Jaroslavsky*

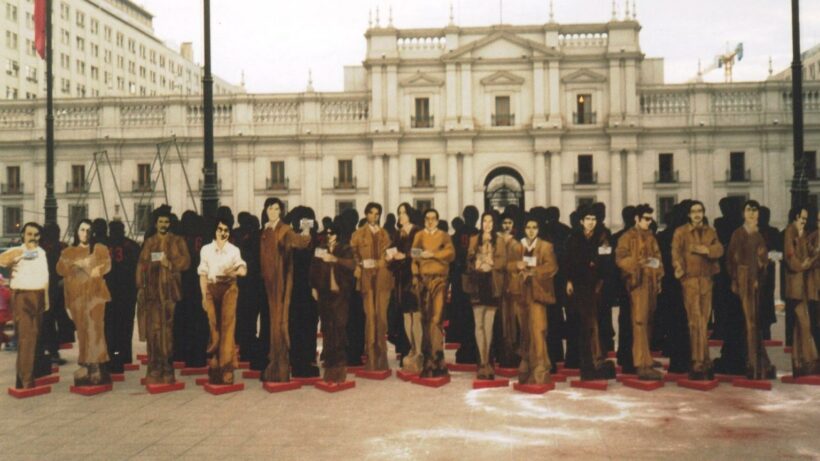

A man strolled his dog again, the laughter of another resonated as it always had and the smile of a young women in a mini-skirt beamed in the chilly, rainy morning. These were three of 119 people forcibly disappeared in Chile between 1974 and 1975 1 , who on July 22 stepped once more upon the streets of Santiago as sepia-tinted larger than life figures, accompanied by 3000 people. It was the Memory and Resistance procession that commemorated a sinister fiction created 48 years ago, known as Operation Colombo.

Photo by Paulo Slachevsky

The main mise-en-scene was a rural road in Pilar, Argentina.

On July 11, 1975, on Chile Street of Pilar, a city of Buenos Aires Province, a Peugeot 504 was found with two charred human bodies inside. Next to the corpses were a cloth napkin with the phrase “Dados de bajo del MIR” (Killed off y MIR) and two undamaged Chilean identity cards, one bearing the name of Luis Alberto Wendelman [sic] Wisniack [sic] and the other that of Jaime Eugenio Robostam [sic] Bravo.

The young architect Luis Guendelman had been taken from his Santiago home by thirteen men on September 2, 1974. Three months later, on New Year’s Eve, sociology student Jaime Robotham was detained on the street. They did not know each other, they were members of different political parties, nor were they taken to the same detention center. Yet, I.D. cards, with names misspelled and childhood photos, were found together in Argentina.

A week later, in the same locale, another body in similar conditions was found, along with an I.D. card of Chilean chemical engineer Juan Carlos Perelman, who had been detained in his house in Santiago five months earlier. 2

Earlier that year, on April 16, in an underground parking garage on Sarmiento Street, Buenos Aires, the first scorched body had been found. Alongside it was an intact identity card with the name of David Silberman Gurovich. The general manager of Chuquicamata, the world’s largest open-pit copper mine that was nationalized by Popular Unity government, was abducted from prison in Santiago by repressive agents in October 1974. Numerous surviving witnesses later saw him in the clandestine torture and detention center on José Domingo Cañas Street.

Relatives of the four forcibly disappeared Chileans traveled to Buenos Aires hoping to at least recover the bodies and accord them a dignified burial. Practically at first sight, they discovered that the bodies were not of their loved ones.

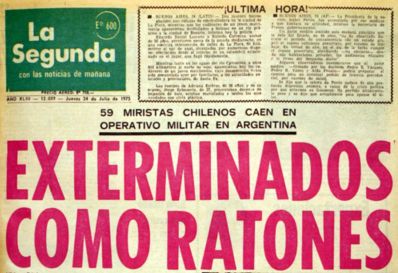

Diario La Segunda

This was the first act of a macabre theatralization. The second act followed shortly.

Since mid-June the Chilean press had been publishing reports concerning alleged presence of Chilean guerrillas in Argentina. On June 25, in Brazil, the newspaper Novo O Día, which had ceased to publish years before, reappeared for a single edition with a list of 59 Chileans "killed in confrontrations with Argentine forces near Salta." On July 15, the single edtion of a magazine called LEA, appeared on newstands, reporting that Chileans had killed each other in internecene battle in Argentina. The two lists summed 119 names. Widely disseminated by the Chilean press, journalist collaborators of the dictatorship wrote false news with titles such as “Ejecutados por sus propios camaradas” (“Executed by their own comrades,” El Mercurio, July 23, 1975) and “Gigantesco operativo militar en Argentina” (“Gigantic military operation in Argentina,” La Segunda, July 24, 1975).

The orchestration sought to give an explanation to those, both in Chile and abroad, who demanded a response. In the 14 months the Military Junta had been in power, more than a thousand people had been summarily killed and the imprisonment of thousands more throughout the country was a known fact.

However, the whereabouts and fate of approximately 800 others was unknown and not acknowledged by the military authority.

At the Pro Paz Committee, created less than a month after the civil-military coup by the Archbishop of Santiago to protect the persecuted and their families, staff people were beginning to grasp that the existence of unacknowledged prisoners actually comprised a systematic practice. In May 1975 the family members of 163 detainees not located in any formal prison facility petitioned the Court of Appeals to investigate those cases. And since the beginning of 1975, the first United Nations Work Group was requesting that Chile permit it to enter and conduct on-site inspections of the human rights situation.

Ten months before formalizing the coordination of the Southern Cone countries in Operation Condor, Argentina and Chile were already collaborating in the military intelligence sphere. The most fearful trans-Andean collaboration thus far was that of September 30, 1974 that resulted in the assassination of former army commander-in-chief Carlos Prats and his wife Sofía Cuthbert, exiled in Buenos Aires.

Operation Colombo capitalized on the presence in Argentina of scores of Chileans who had fled there after the military coup. Upon arriving, many were counseled to say they had come from Mendoza, where Argentines speak with an accent similar to Chilean Spanish, because Chileans were said to be suspect.

Silberman, Perelman and Guendelman were the only Jewish surnames (Robotham was not, but sounded as if it could be Jewish) associated with the hoax of the 119 names. The antisemitic element that would become a hallmark of Argentine repression did not form a part of the Chilean repressive practice.

Therefore, it is likely that the Argentine partners of the scheme contributed that facet. Argentina provided a propitious stage for a montage that aimed to further conceal the fate of people whose detention was systematically denied. For the Argentine military, the staging reinforced the notion that their national territory was besieged by international subversives who plotted with nationals to produce a dangerous instability, that called for tough action by the state. It sowed the ground for what was to come, already in full swing in Tucumán through plan Independencia. 3

For family members of forcibly disappeared detainees, Operation Colombo was devastating. They did not believe that their loved ones had killed each other in Argentina, but the confabulation increased their doubts. Aside from the known graves with the initials NN (No Name), in subsequent years, other clues would surface, particularly in 1978 with the discovery of the remains of 15 people detained in 1973 in the lime kiln at Lonquen, south of Santiago. But the List of 119 names was the first concrete indication.

Photo by Paulo Slachevsky

The third act takes place in the judicial arena.

The deceased judge Juan Guzmán Tapia, who in 2000 became the first to charge Augusto Pinochet, once commented that Operation Colombo was easy to prove. In 2005, Pinochet was charged again, this time for Operation Colombo and, in 2008, 98 higher-ups and former agents of the DINA secret police were indicted for the abduction of 60 women and men whose names appear in the list of 119. However, the identity fraud and the crimes related to the four bodies used in the phase prior to the List of the 119 has not been investigated. Eleven days after the discovery, the bodies were buried in unknown locations without an inquest, without knowing their true identities and circumstances of their deaths. But some information does exist, even fingerprints of at least one of the victims found in the car in Pilar, according to court sources. Jorge Robotham, an older brother of Jaime, calls Argentine and Chilean judiciary authority to investigate this phase of the orchestration to unveil how it was organized.

Pablo Llonto, the Argentine attorney who represents Robotham in this case, notes, “Several Operation Colombos were mounted in Argentina, all from the same mold: false operations and false confrontations.

They thus concealed hundreds of shootings and murders committed by the armed forces and police, with complicity by communications media directors, who have never expressed remorse or have never apologized.” 4

The curtain has yet to fall on the last scene of this drama.

Half a century after a day in September that left scars on Chilean society, there are links between that military coup and the one that was about to befall Argentina that have not been thoroughly investigated.

The names David Silberman, Luis Guendelman, Jaime Robotham and Juan Carlos Perelman, whose identities were stolen to conceal the truth, could be key in bringing justice at last.

*Maxine Lowy Jaroslavsky, a journalist who lives in Santiago, Chile, is the author of Latent Memory: Human Rights and Jewish Identity in Pinochet’s Chile (University of Wisconsin 2022).

1 It did not include everyone who had been detained and disappeared thus far, for example, none from the first four months after the coup.

2 The search for his brother Juan Carlos is the subject of filmmaker Pablo Perelman’s movie Imagen Latente.

3 In February 1975, General Acdel Vilas, with full support from president Maria Estela Martínez de Perón, unleashed Operación Independencia,

featuring abductions, detention in secret prisons, the denial of arrests, torture and the concealment of the bodies of murdered people. An

estimated 300 people were summarily executed or forcibly disappeared in Tucumán before the March 1976 coup. One of them was Máximo

Jaroslavsky, this author.’s cousin.

4 Email correspondence of 7-26-2023.