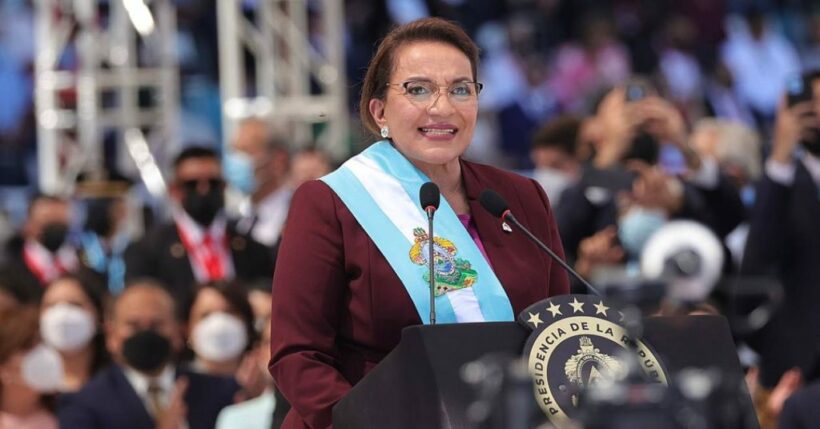

In the context of the fundamental contradiction of confrontation between the government and its initiatives presided over by Xiomara Castro Sarmiento and the powerful and active de facto groups – which range from official political parties, to business associations, to individuals with specific power, to the slippery and subterranean networks of organised crime, particularly drug trafficking – all of which are linked to each other and are linked to the government’s initiatives, all of them linked to each other and to high-ranking police and Armed Forces officers – which characterises the current Honduran context and which is becoming more acute in 2023 and which is expected to become even more polarised in the next two years.

By: Ismael Moreno, SJ. 14 years after the coup d’état.

We call on you to situate ourselves and seek a response to the following national conflicts that could currently put us in check and lose us if we do not know how to analyse, interpret, discern and confront each one, but from a joint look and commitment:

The first conflict is the agrarian conflict,

A conflict that has been accumulated and never resolved for at least six decades. All the responses given by the different public administrations have been to accumulate the conflict and use it to serve the interests of power groups or for proselytising campaigns. It has always been said that in Honduras whoever has the land has the power, and this is still the case today, but it has increased with territorial control, because it is no longer the rural actors, landowners, big businessmen and peasants, but organised crime, both urban and rural, who have no special interest in land for production or trade, but rather territorial control for illicit purposes and the transit of dirty business and drug trafficking.

The government’s creation of the Commission for Agrarian Security and Access to Land sends a very bad signal when it accentuates evictions and the criminalisation of peasant organisations over agrarian reorganisation that would drastically change land tenure, the basis of the historic agrarian conflict. And as long as this fundamental issue is not addressed, any response will be one of blindly playing at prolonging the conflict, aggravating it, or primarily responding to the pressures and blackmail of the oligarchic business elite. The murders of land defenders, especially in the Aguán area, add to the blood spilled over many years of this accumulated and unresolved conflict, and if we continue to give superficial responses we will not only continue to stumble, but we will have to continue lamenting and mourning more peasant bloodshed.

The call to the social and popular sectors must be oriented towards exercising the right to social pressure and mobilisation so that the government approves and implements public policies that, instead of being fire extinguishers and responding to pressure from power groups, are committed to thoroughly touching land tenure as the fundamental agrarian crux of the country, And as a condition for advancing in these agrarian reorganisation policies, we demand that the National Congress repeal the Law for the Modernisation and Development of the Agricultural Sector as a condition for achieving a scenario in which the peasantry becomes a decisive actor in the construction of comprehensive agrarian proposals.

The second conflict is the environmental-ecological conflict.

A conflict that is leaving a bloody trail of deaths of environmentalists and defenders of rivers, water, forests, territories and cultures, as well as the stigmatisation, criminalisation and prosecution of those who oppose with community and patriotic fervour the dispossession of natural resources, their territories and their cultures. This is what happened years ago with the assassination of Berta Cáceres and the murders of environmental defenders in the Aguán area, specifically in the community of Guapinol, in the area of the San Pedro River, in the Aguán region and with environmental defenders of the Tolupan indigenous tribes in the mountains of the its interior of the department of Yoro, among others. We reiterate that this environmental conflict has at its core the confrontation between two models, one, the development model based on the dispossession and infinite exploitation of nature’s goods for commercial purposes, profit and gain, and at the other extreme, the model of good living based on the harmonisation between nature’s goods and human beings. Both human beings have human rights to defend and promote and nature has rights to defend and promote. This harmonisation is what will give us life, because in this way nature will give us what we need to live and achieve wellbeing and we will give life and protect nature as our mother.

Our commitment must come from the communities and organisations that protect and defend nature, and at the same time from the struggle against the extractivist development model, in order to contribute to the consolidation of the model of good living and to the weakening and drastic reduction of the destructive dynamics of the extractivist development model. This contradiction between these two models is at the root of the violence, threats to life and assassinations of environmentalists and social and popular activists who defend the goods of nature. It is a very bad thing for the government if it promotes lukewarm, murky and ambiguous responses in a conflict that incubates so much violence, and without taking a stand in defence of the lives of leaders and communities and from the model of good living. Such responses only contribute to prolonging this conflict and to leaving those of us who defend the model of good living under greater threat. We call on the government to define its position with public policies aimed at strengthening the model of good living, from where the commitment to defend those who protect and give their lives for their natural resources, their territories and their culture is inserted.

The third conflict is that of human rights.

A conflict that is inserted in a society where human rights are not violated individually, but rather where society is subjected to a structural model that violates human rights, and which has to do with agrarian and environmental issues and everything related to the absence of an institutional system of justice and a legality in the hands of those who violate the human and labour rights of workers and at the service of business, political and criminal elites. Human rights violations take place in a context of impunity and corruption. Addressing human rights issues in isolation and without a holistic look, as seems to be done by the public administration, is to continue to take blind steps, and is based on a sectoral and not a structural understanding of human rights. We urge to respond to the demand for human rights from a comprehensive and structural look that links this struggle to the issues of agrarian, environmental, violence, justice and commitment to an option for the oppressed and marginalised sectors.

The fourth conflict is the situation of violence and insecurity.

We live and witness dramatic and extreme situations of violence such as what happened in the women’s prison in Támara, in Francisco Morazán, the bloody events linked to operations and murders in the context of organised crime and the massacres that frequently occur in the country, leaving trails of blood like the one that occurred in Choloma on the weekend of 24 June that left at least 11 people massacred and in a context in which some 25 people died violently in a single day on the northern Honduran coast. The escalation of violence is occurring simultaneously with acts and decisions that, while apparently isolated, could be situated within the framework of weakening and undermining the national and international credibility of the government led by Xiomara Castro, such as the cases of the denunciation of threats and the departure from the country of the director of the National Anti-Corruption Council and the dismissal of the Secretary of Security, who has enjoyed the confidence of the US government. The violence is preoccupying and is a symptom of social and institutional deterioration, as well as of the government’s weakness and inadequacies in the face of insecurity and a sign of the active and threatening presence of the structures of the narco-dictatorship.

This situation of violence without the state’s capacity to control it through the government is the consequence of several decades, specifically since the 1990s, when the state lost control over the administration and monopoly of violence, and this was delegated to non-state sectors through the Armed Forces and the police. This delegation formally began with the creation of private security agencies under the ownership of high-ranking army officers, which over time proliferated and increased their membership to more than 150,000 personnel, far more than the number of military and police personnel combined.

This delegation to private security agencies had such a far-reaching effect that private security guards came to perform army and police functions. The same delegation was given to paramilitary groups of private businessmen such as the late Miguel Facussé in the Aguán region or to the Atala family in areas of western and northern coastal Honduras, one of the immediate consequences of which was the crime committed by these private groups against Berta Cáceres. From these delegations, the consequent delegations to irregular and violent groups such as drug traffickers, gangs and maras gained force. After several decades of these processes of delegation, the state has lost control and has ended up the victim of the very sectors in which it has placed a violence that should never have lost its monopoly as a strict function of the state.

Organised crime undoubtedly seeks to put the government in check in order to weaken and destroy it, while at the same time seeking to measure force in order to define who in Honduras has the real power. The appeal is to the government not to let desperation or threats lead to decisions in the face of violence and insecurity. We warn that it is not the weight of force or weapons alone that will resolve the conflict of violence. This conflict is embedded in and refers to structural issues, some of which are noted in this position paper. It is not the military solution that will resolve this conflict. The military has been a factor of problems and human rights violations in the history of our country, and nothing different has happened to expect a significant change in their conduct and behaviour.

Bad advisors are those who claim a military solution to the violence and the penitentiary system. Bad advisors are those who argue for the prolongation of the state of emergency in the manner of neighbouring El Salvador. Responding only with force and violence leads to new dynamics of violence. It is an obligation to call on and pressure the government to convene various sectors of society so that, together with the government and the LIBRE party, they form a multidisciplinary body that, together with an international presence, addresses violence from its structural perspective, and leads to the design of a short, medium and long-term proposal that is fair and lasting, and in harmony with the other factors of national conflict, leads to reducing and eventually eradicating the factors that currently produce violence.

The fifth conflict is ungovernability.

The government has a share of power, but President Castro has the lowest share of this power, and many of the decisions are made outside the formal institutions of the three branches of government, and the de facto power groups use them to channel and ratify the decisions made in other informal spaces, even outside the trade union bodies, as a senior businessman put it: “I don’t need the government, I make my decisions and then channel them through my unions”. There is a share of power in government, but it is neither the largest nor the most important share. Power is felt outside the government, and power is exercised from formal and non-formal, irregular and underground bodies, often influencing decisions made in the Presidential House, the National Congress and the Supreme Court of Justice.

Power is disseminated in different places and spaces, from which pressure is exerted and the government is conditioned. These are the de facto powers, from which emanate diverse manipulations and arbitrariness that constitute and give consistency to impunity, corruption and violence. This is what we can identify as ungovernability. Autonomous powers, like a kingdom of Taifas, each one promoting its own dynamics and seeking to impose its interests over the others, to the detriment of the power and interests of the state, because at the end of the day, each power acts as if it were, in fact, the state.

The call is to contribute to the construction of links between different sectors of society to build and rebuild broken fabrics while unifying alliances between organisations and so many “scattered vigours” to articulate proposals to be presented and defended before the government. The more we strengthen power from below and link up different sectors, the more we can contribute to generating popular power that pressures the state from below. And the more popular power that is built up, the more we can influence the government, to whom we would thus be transferring the power they need to promote public proposals and policies over the de facto powers that each of them seeks to impose by competing with the power of the state. The alliance between popular sectors linked horizontally with a government to which power is handed over so that it can administer it on the basis of popular interests is an essential political task in these times of ungovernability.

The sixth conflict is the CICIH.

Everyone is talking about and demanding the presence and installation of the CICIH as an international body that, attached to the UN, will contribute to investigating and bringing to trial and conviction those who, from the criminal networks, sustain the institutional framework of impunity and corruption in our country. This facility must be in full harmony with the national justice bodies, both the Supreme Court of Justice and the Public Prosecutor’s Office. If the CSJ does not function or respond to interests that are alien to the demands of the Constitution of the Republic, there is very little an international body can do. Decisions in the plenary session of the CSJ, such as agreeing to allow a confessed drug trafficker to defend himself at liberty, send very bad signals, or having on the agenda of the first plenary session of the CSJ the issue of reforming the extradition decree, warns that this institution continues to move in accordance with the interests of the powers that be and not by virtue of the function dictated by the Constitution of the Republic. If we allow ourselves to be carried away by rumours that the election of the Attorney General and his Deputy have already been negotiated and that the process established for his election is merely a matter of protocol, he warns that the Public Prosecutor’s Office will continue to be co-opted by sectors of the powers that be. Under these conditions, there is little to be expected from an international body. And if we add to this the fact that the dynamics could point to the fact that the installation of the CICIH is not denied, as long as its formation is subordinated to and controlled by those who sustain and lead the Pact of Impunity.

The call to the diverse social and popular sectors to maintain our look and vigilance so that the installation of the CICIH is achieved without the pressures and conditions of those who lead the current political parties, the business associations and organised crime, but that it remains independent, even from the government, so that it can fulfil its function of investigating criminal networks in depth. We believe in the need for an international body such as the CICIH, without which it is impossible to successfully combat the impunity of those who have immense power in public and private institutions and in the underground corridors of organised crime. However, in order for the CSJ and the Public Prosecutor’s Office to fulfil their function, we must demand and be vigilant so that they function in accordance with the constitutional mandate and are not subordinated to interests that are alien to their function. And social and political vigilance is necessary so that these national bodies and the CICIH maintain independence in their decisions and do not allow bribery by those who are identified or suspected of having links to acts and processes of impunity and criminality.

The seventh conflict has to do with the ZEDE and the proposed Tax Justice Law.

The ZEDE is part of the fundamental confrontation between the official sector and the de facto groups, because it has to do with the struggle to repeal instruments that are a direct attack on national sovereignty and behind which lie the interests of transnational corporations that, in association with the Honduran business elite, seek to consolidate the neoliberal capitalist model in its most radical and extremist expression, whose main promoters call themselves “libertarians” who unambiguously sweep away territoriality, natural assets and the national responsibility to exercise sovereignty in compliance with constitutional mandates.

The call is clear so that the various social and popular sectors converge in common pressure to demand that the National Congress ratify the vote for the definitive repeal of the ZEDE, as a popular expression so that in Honduras we exercise the right to sovereignty that the Constitution of the Republic grants us. We join it to the bill that the Executive presented to the National Congress to approve the instrument called Tax Justice, aimed at exercising control over financial and economic decisions in order to reduce, through State institutions, the economic imbalances and inequalities that occur in commercial, productive, financial and tax relations. In Honduras we are impoverished not only because the means of production are in very few hands and because of the decision to depend on foreign economies external to endogenous dynamics, but also because the population produces wealth socially, but there is a system of taxation that leads to wealth being appropriated individually. Salaried people pay the same as top businessmen, and with this legal figure of Tax Justice, the aim is to change the rules so that people pay taxes to the state according to their income and earnings. Applauding this initiative is appropriate for those of us who believe in and value social and popular transformations, and at the same time we must urge all patriotic social and popular sectors to join in the struggle to demand its approval in the National Congress.

The eighth conflict is the energy conflict.

We are a country with all the privileged natural and biodiversity conditions to have effective and reserve energy to cover present and future energy needs, and also to sell to our neighbouring countries. However, we are experiencing and suffering the consequences of the corrupt and evil energy administration of previous administrations, which has been geared to perverse use for peculiarity, to the privatisation of that administration and with irresponsible and at least mediocre responses from those directly responsible for public administration. Today we are paying the bill, which is also leaving energy on a silver platter in the hands of the oligarchic business elite and transnationals.

The call is for the government to place competent, professional, honest and forward-looking personnel in the energy administration, to unite the resolution of the current crisis hand in hand with patriotic sectors of the country and to be assisted by people and countries with high experience in the field, such as Brazil, Mexico, Norway and China, so that together they can solve the energy crisis, Norway and China to jointly implement a comprehensive proposal to provide clean energy to the whole society, to guarantee its non-privatisation and to involve various popular sectors of non-governmental society in order to ensure that the energy administration is permanently cleaned up and that it is associated with the defence and protection of the environment.

The ninth conflict is international.

After living in a standard context of international diplomatic relations conditioned by the interests of the US government, Xiomara Castro’s administration took and implemented the decision to establish diplomatic relations with People’s China, maintaining its traditional relations with the remaining governments of the international community, leaving Taiwan to make effective the decision to withdraw its diplomatic representation when the condition of maintaining it in exchange for Honduras not establishing relations with People’s China was broken. It is a decision that opens up enormous expectations and opportunities. We applaud this decision and hope that the government will seize the opportunity to strengthen its international relations and turn them into possibilities for the wellbeing of traditionally excluded and oppressed sectors, and at the same time that this opportunity will go hand in hand with the government’s commitment to promoting internal proposals that will allow progress towards sovereignty, independence, self-determination and social justice, and not be a new factor of dependence, updating the “banana nostalgia”.

Our preoccupation and exhortation:

The situation in the current context is of great preoccupation concerning the deterioration of the current public administration due to internal conflicts based on struggles for quotas of power and with an excessive look at the electoral contest. This internal deterioration aggravates the deterioration of the social and political environment, which places the entire country in a state of alarm and danger. It is preoccupying that instead of helping the LIBRE party and related sectors to consolidate a responsible stance on the fundamental contradictions of the current national political context, they are weakening themselves in fruitless and sterile internal struggles that are turning the state’s institutionality into an electoral structure.

With such an environment and problems, Honduran society as a whole loses out, because this government is the only platform, we have in the country to build a democratic proposal, and the responsibility for making timely critical questions, sustaining and enriching it, belongs to all the people and organisations, social, popular, political and ecclesiastical, who believe in and want to bet on democracy and the rule of law.

If this project fails, as the national and international anti-democratic sectors are seeking and promoting it, and as the sectors within its interior government are promoting it, there will be no other opportunity in the short and medium term. If this proposal is thwarted and destroyed, we are likely to see a return to the recent past, but with greater radicalism and extremism. The various sectors of the narco-dictatorship are regrouping and using all the contradictions, errors, weaknesses and mistakes to destroy and prevent this proposal from becoming a national democratising project, and thus promote their proposal, which would be expressed in a broad coalition that brings together sectors, groups, parties and movements based on a project of the fundamentalist right and extreme right, politically, ideologically, religiously and militarily conceived as neo-fascist.

These sectors have a clear idea of their project and are moving towards making it a reality in the next elections. This project can be expressed in a political party, such as the National Party or the Liberal Party, but in coalition among themselves and with the current Salvador Party of Honduras, or it can be expressed in a coalition of fundamentalist religious parties and movements channelled through an “outsider” who represents them and gives them guarantees of victory. This project is based on the condition of discrediting and taking advantage of LIBRE’s inconsistencies, internal conflicts and unresolved social demands in order to destroy the potentially democratising project led by Xiomara Castro’s government. The right and the extreme right have clarity and firmness in their proposal and are consolidating towards its implementation.

The sectors, especially LIBRE, which are leading it and rallying around the institutionality of the state, are wallowing in their own internal contradictions, and by losing the overall look and the fundamental contraction, they are aggravating their conflicts and behaving as if they were fundamental. They have a lot of agitational language and slogans, but very little solidity, and the internal conflicts and the desperation to achieve quotas that position them with power to make their electoral political aspirations a reality, not only weakens and tarnishes the democratising proposal, but in fact torpedoes it and is a factor that ultimately favours the firm and solid anti-democratic project whose shadow is increasingly overshadowing us and making its big animal step felt.

The call is especially to the leadership and internal currents of LIBRE and to government officials to responsibly review their actions and attitudes, and to place the fundamental contradiction that confronts the democratising proposal of the government with the powers that be, and to place peculiarities and group interests, however important they may be and appear to be, We urge them to subordinate genuine interests of political proselytism, to stop seeing the government as an electoral platform and turn it into what it should be, a national platform for the construction of a national and political project for national sovereignty and self-determination of the Honduran people. Time for this is running out, the enemies of democracy and the rule of law are lurking and threatening. There is no time to lose, either we place our differences and interests in the appropriate secondary place to look at the whole and bet on saving and reorienting the democratising project by really and not by demagogy, a single mooring in a positive and creative way with the most responsible team led by Xiomara Castro Sarmiento, or we will witness the emergence of a neo-fascist fundamentalist coalition that will crush the popular aspirations. Today, we are in time to act, tomorrow will be too late.

A special appeal is made to social, popular, environmental, agrarian, ethnic, youth, women’s, ecclesiastical and advocacy organisations, to accentuate the overall look, the critical and at the same time proactive analysis, and to open ourselves to links and coordination, accentuating coincidences over differences, distrust and protagonism, which are undoubtedly secondary. To move forward so that the overall look is expressed organically in calls aimed at committing ourselves to strengthening the method of organised pressure around national demands accompanied by proposals. To insist that we are not and do not want to be the government, but in the current period the government is not our enemy. We are called to strengthen the structures that bring together the popular movement, and from such an instance contribute to establishing links with government bodies, based on autonomy and guaranteeing the social identity of the movements. The final call is to create all the conditions of consciousness, organisation and militancy to turn this period into the time of leadership and coordinated force of the social movements.