The triumph of the far-right José Antonio Kast in the Chilean constituent elections is a symptom of the reconfiguration of the opposition to progressive governments that began in Brazil and extends to countries such as Colombia and Argentina with the histrionic “libertarian” Javier Milei.

In November last year, Mexico City hosted a new edition of the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), which has been held since 1974 in the United States and which each year provides a poll that serves as a thermometer to define the toughest Republican candidates. It had only been held in one Latin American country before: Jair Bolsonaro’s Brazil.

Mexico brought together some of the main international leaders of the space, such as the Americans Steve Bannon and Ted Cruz and the Spaniard Santiago Abascal, as well as representatives of the regional right, such as Eduardo Bolsonaro (Brazil), José Antonio Kast (Chile), Alejandro Giammattei (Guatemala) and Javier Milei (Argentina).

The new Latin American political map may show a dominance of the left and progressivism, but it does not hide the rise of extreme right-wing forces throughout the region. They are not in government, but they could be. They went from being opposition to alternative. Electoral legitimisation led them to change their strategy and discourse, given the prospect that almost 30 percent of citizens – according to Latinobarómetro – are indifferent to the type of political regime they live under.

The far right began to incorporate issues from the global agenda. One of the driving forces behind this strategy was former Polish president Lech Walesa, at the Mexican meeting, when he pointed out that climate change is a real problem. The strategy is to adopt ideas or proposals from the adversary in order to contest his support base.

It is true that the Latin American right has recently suffered major setbacks (Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia), but it maintains significant weight in the region. The question that remains is what place dissidents occupy in the face of the neo-fascist advance. Because the libertarian ode to economic disaster is accompanied by a clear attack on the rights of women and dissidents. Gone are the days of the xenophobic and racist ultra-right against immigrants. Now xenophobia includes all progressivism and the left when it governs, because for them it is an evil will that prevents the free assumption of a compact identity.

Discussing this unleashed vision is as difficult as trying to reassure children of the ghosts that haunt them. This is why immigrants, workers and vulnerable people of all kinds when they vote for the far right do not do so against their interests. They have other interests, more opaque than vital and economic interests, points out the Argentinean psychoanalyst Jorge Alemán.

It is about enjoying an identity as in football stadiums, beyond any historical or problematic dimension, and being able to enjoy the defamation and insults uttered by an “I” that struts its mirage until it is awakened by the real thing, he adds.

Annihilating the traditional right

Brazil was a pioneer in the annihilation of the classical right. The ultra-right-wing Jair Bolsonaro lost the last presidential elections by a slim margin, despite the fact that he came from a position of denialism in the management of a pandemic that killed 700,000 Brazilians and was up against Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the undisputed leader of the Brazilian left, in the polls.

Bolsonaro, with his coup threats, isolationist diplomacy and misogyny, was defeated at the polls in 2022 despite winning more votes than he did in 2018, reflecting the power of the political movement he leads and the deep-seated hatred of the Workers’ Party.

In Chile, Kast raised the unease of the citizenry which, in the social outburst of 2019, was the main cause of the left. Today, the unease can be explained by three crises: public security – an increase in organised crime and violence -, the economic crisis and the one that has broken out in the north of the country, with irregular immigration.

In Colombia, the right was slow to react to the 2022 elections when the leftist Gustavo Petro won, lost representation in Congress and was left without a clear leader after former president Álvaro Uribe saw his favouritism shattered in an ongoing judicial scandal.

The Colombian right seems to be drifting towards more extreme positions, such as those embodied by Uribista senator María Fernanda Cabal, who is close to retired military officers and who has said of the government that “communism is what we are living”, after a retired colonel said of the president “we are going to try to do our best to oust a guy who was a guerrilla fighter”.

In Peru, all variants of the right united forces in Peru to consummate the recent coup that toppled Pedro Castillo. They harassed him until they finally forced him out of office. They did not tolerate the presence of a president alien to the Fujimorism conspiracy with its allies and adversaries, which sustains the most anti-democratic political regime in the region.

Since 2018, the right-wingers have been displacing the six presidents who have lost functionality for the continuity of the regime. This system was created by Fujimori a year after he took office (1993), by means of a constitutional device that grants the judiciary and the Public Prosecutor’s Office all-encompassing powers to intervene in political life.

The weakness of the executive, the atomisation of the legislature and the gravitas of the courts underpin a system that fosters immobility, apathy and disbelief among the population. The aim of this scheme is to ensure the continuity of a neoliberal model divorced from the vicissitudes of politics. The dizzying change of presidents contrasts, for example, with the permanence of the same president of the Central Bank over the last 20 years.

This time they carried out an extreme variant of lawfare, through a parliamentary coup with a military foundation and the complicity of Vice-President Boluarte. They immediately unleashed a ferocious repression, with dozens of people killed, hundreds arrested and curfews in several provinces. This criminalisation of protests goes beyond recent precedents and has placed the army in the typical place of any dictatorship (Rodríguez Gelfenstein, 2022).

In other countries more accustomed to repressive state management, the new right offers little new. In Ecuador or Guatemala, it simply underpins the periodic reinstallation of exceptional regimes, with the consequent militarisation of everyday life. There it sustains variants of coups, replacing the old military tyrannies with more disguised forms of civilian dictatorship, notes Claudio Katz.

In Haiti, the ultra-rightists sponsor both foreign intervention and the expansion of the mafia gangs that have destroyed the island’s social fabric. They prop up the model of gangster coups that replaced the political system and oscillate between promoting a traditional dictatorship or precipitating another US occupation.

Anarcho-capitalists?

In Argentina, Milei, an ultra-liberal economist, offers himself to the electorate as an “anarcho-capitalist” who promises to end the “political caste”, reduce the state to a minimum, hand over the administration of education and health to private capital and, above all, solve chronic inflation with a dollarisation of the economy.

The expansion of the far right in Argentina is recent and, as in Brazil, it emerged in confrontation with a centre-left government. The first glimmers of street marches against Kirchnerism were captured by traditional conservatism and catapulted the neoliberal Mauricio Macri into government. But in the subsequent virulent contestation of Alberto Fernández and Cristina Kirchner, Milei’s (and to a lesser extent Espert’s) reactionary force emerged.

The capacity for action of libertarian figures was marginal in Argentina during Macrismo, but it has expanded in proportion to the widespread disappointment with the current government and today they dispute spaces with the traditional right. They maintain a profile of their own that threatens the unity of the opposition in the upcoming elections. In this potential division lies the ruling party’s expectation that it will remain in the race to retain the presidency. In Argentina today, the army plays a marginal political role in a country that has developed enormous antibodies to militarism.

It is worth remembering that Milei jumped into politics from the television studios, where he made the audience rise with shouts, insults and proposals in favour of the free sale of organs or children. When in the 2019 legislative elections he won a seat in Congress, he ceased to be a spectacle and became a problem for the right and the left.

Milei threatens the traditional right like no other politician since the return to democracy in 1983. He likes to toe the line of Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, with the particularity that in Argentina he has no political structure whatsoever. His power lies in the growth of the protest vote of young people who no longer trust politicians and are fed up with the economic crisis.

The traditional right, represented by former president Mauricio Macri and his Juntos por el Cambio alliance, is not clear if the best strategy is to co-opt or confront Milei. For the moment, the economist’s incendiary discourse has forced lifelong liberals to radicalise their right-wing discourse, fearful of the votes they see losing every day in the polls.

In Mexico, the far right has less momentum than in other countries in the region and has settled into the loopholes of the conservative National Action Party. Some of its leaders came to the fore in September 2021, when Spanish far-right leader Santiago Abascal arrived in Mexico with an agenda ready to unleash a political storm.

Dozens of Mexican politicians were photographed with the Vox leader and signed the Madrid Charter, a kind of crusade against communism that accuses left-wing governments in Latin America of being “totalitarian regimes”. Mexican ultra-rightists soon backed away from supporting Abascal, although others took the opportunity to come out in the open.

Another part of the right – the Frente Nacional Anti-Amlo (FRENA) – took over the capital’s Zócalo with a hundred tents between September and November 2020 to protest against “the dictator López”. The movement, born in the north of the country, close to the United States, claims to represent “millions of empathetic Mexicans” and is inspired by the US Tea Party.

In November, the Conservative Action Political Conference met in the Mexican capital, an ultra-conservative event attended by Abascal; Steve Bannon, former advisor to Donald Trump; the Brazilian Eduardo Bolsonaro; and the Argentinian Javier Milei.

In Argentina, the publication of the electoral platform of La Libertad Avanza, Javier Milei’s party, makes clear a course of stripping away rights and making life even more precarious. Abolishing the minimum wage, trade unions and pensions, the liberalisation of the purchase and sale of arms and the repeal of the law on abortion and Comprehensive Sex Education.

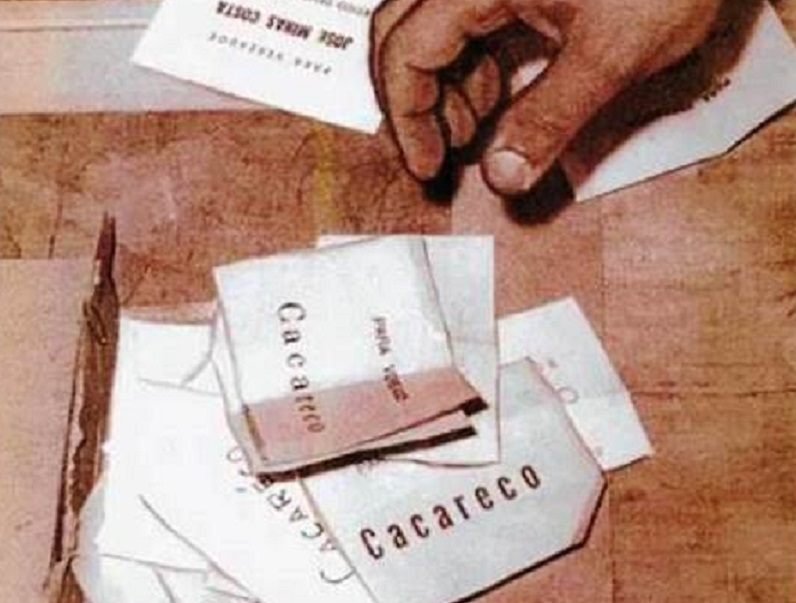

Cacareco

Sometimes society is tired of its politicians – many of whom behave like an elephant in a bazaar – and they show their weariness in the most ingenious way possible. Often it is by electing someone who appears to be an outsider. But in 1959, the punishment vote of society in Brazil’s Sao Paulo was directed at an animal: a rhinoceros “won” an election.

Dirty and unkempt pavements, unpaved streets, unfinished public works, corruption and food shortages in the poorest districts were among his preoccupations. Frustration and ingenuity. Frustration of the people of São Paulo, ingenuity of a group of university students, who came up with the idea of choosing an animal to participate alongside the 540 candidates vying for the 45 City Council seats that were up for grabs.

“Cacareco”, a four-year-old rhinoceros living in the city’s zoo, was the protagonist of the punishment vote. One of those Paulista students was categorical when he painted the mural: “Better choose a rhinoceros than a donkey”.

And Cacareco (which means rubbish) swept the polls. Paulistas voted en masse against the corruption and negligence of the political class. On 4 October 1959, the rhinoceros got 100,000 votes, while the first human candidate barely got 10,000. In any case, the abstention was also large.

The humiliation was so great that one candidate even took his own life after the results. The authorities annulled Cacareco’s votes and everything went ahead in a new election. (Cacareco died prematurely in December 1962, at the age of 8. His remains are on display at the Veterinary Anatomy Museum of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Zootechnics of the University of São Paulo).

Cacareco was the inspiration for the Rhinoceros Party of Canada, a political party that ran in elections between 1963 and 1993, which had a clearly humorous and satirical intent. Its main promise was “not to keep any of our promises”. It was created by Jacques Ferron in 1963 and proclaimed as its ideological leader Cornelius the First, a rhinoceros from the Granby Zoo in Montreal.

In 1988, the magazine Casseta Popular directed the candidacy for mayor of Rio de Janeiro of the monkey Tião. He was supported by writer and then legislator Fernando Gabeira of the Green Party. The chimpanzee’s Bananista Party won 400,000 votes and was the third most voted candidate among the 12 candidates running.

Tião was registered in the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s most voted monkey. He died on 23 December 1996 at the age of 33 from diabetes. A monument with his figure was erected in the Rio de Janeiro Zoo.

No further comment: I’ll stick with Cacareco.