On 4 July 1976 in Algiers, the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Peoples was proclaimed. It was the result of a complex process that coincided with the emergence of many new nations in Africa and Asia, the fruit of the yearning for self-determination of the peoples that cemented the fall of colonial domination.

As the website of the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal points out, the Algiers Charter was born out of the collaboration of jurists, economists and political figures, a large number of representatives of peoples’ liberation movements and many non-governmental organisations, among its main promoters being the Lelio Basso International Foundation for the Law and Liberation of Peoples, together with the International League for the Rights and Liberation of Peoples.

Algiers was chosen because it was a strategic reference point for the non-aligned countries, the capital of a nation that had to fight hard to emancipate itself from colonial domination in a continent with many countries struggling for political and economic independence.

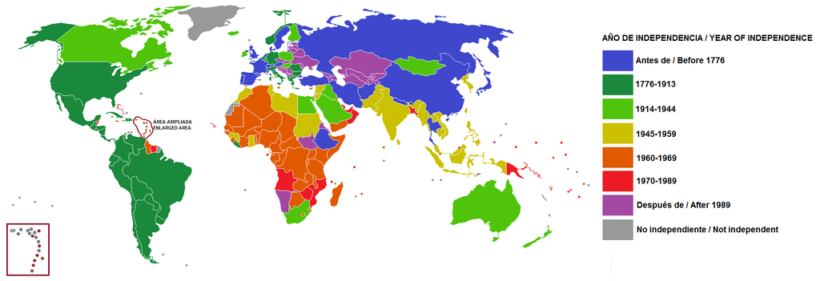

Moreover, the date of the signing of the Charter symbolically coincided with the bicentenary of the Declaration of Philadelphia, by which the representatives of the thirteen English colonies of North America adopted the Declaration of Independence of the United States, proclaiming the right to be free and independent from the British Crown.

Signed by more than 80 political and cultural figures from all over the world, the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Peoples expresses the “conviction that effective respect for the rights of man implies respect for the rights of peoples”. Its 30 short articles explain and codify this collective extension of individual rights: the right to national and cultural identity; the right to political and economic self-determination; the right to culture, to the environment, to common resources; the right of minorities and the guarantees necessary for it to make these rights effective.

In the introduction to this important document, which has served as the basis for the subsequent work of the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, one can read a context that even today, several decades after, has not completely lost its relevance.

“Imperialism, with perfidious and brutal procedures, with the complicity of often self-appointed governments, continues to dominate a part of the world. Intervening directly and

indirectly, through multinational corporations, corrupt local politicians, aiding corrupt regimes and military regimes that rely on police repression, torture and the physical extermination of opponents; by a set of practices that are called neo-colonialism, colonialist, imperialism extends its domination over numerous peoples”.

And just as then, the imposition of unjust schemes, whether by brute force or through more subtle tools, does not have the blind acceptance of the peoples. Despite all the manoeuvres, setbacks, delays or even mistakes of the moment, nothing can stop the intentionality of the peoples towards their emancipation.

In a framework of accelerated globalisation, marked by full connection and interdependence, this drive for liberation must now be translated into collaboration and convergence, leaving behind all traces of domination or competition. Although it is difficult today to see the signs of a new world and a new moment in history, planetary civilisation has begun and is already showing the blueprint for the future: the construction of a Universal Human Nation.