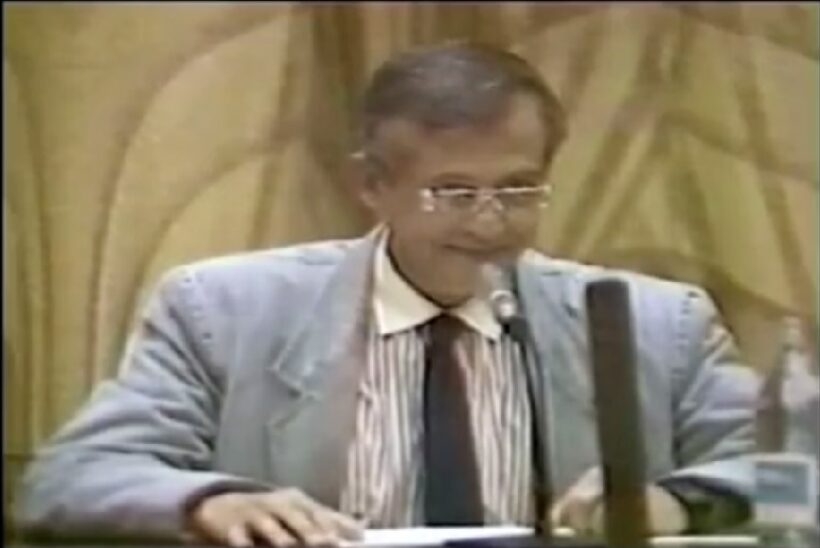

On 18 June 1992, an event of singular significance took place. At the Russian Academy of Sciences, the humanist thinker Silo gave a lecture on “The Crisis of Civilisation and Humanism”.

Unnoticed or usually silenced by the hegemonic Western press, which at the time only cheered “the end of History”, the founder of the New Humanism current, at the invitation of the Russian Club of Humanist Intentions, shared his vision of the events unfolding, as he pointed out “in this area of the planet more than in any other, where the most formidable acceleration of the conditions of historical change is taking place; a confused and painful acceleration in which a new moment of civilisation is being gestated”.

Probably already, in the midst of the victory, however ephemeral, of the capitalist bloc subordinated to corporate interests over socialist centralism in its moment of decadence, Silo foresaw the possibility of an emerging multipolar mentality, a new outbreak of self-determination and recognition of diversity, which beyond the still prevailing violence and war, will bring a convergence between nations that will prevail over the brutal competition, as is now beginning to be seen in the geopolitical winds blowing from the East.

At the time, Silo characterised the civilisational crisis with concepts that could well be applied to the present situation.

“To characterise the crisis…”, we can look at four phenomena that have a direct impact on us, namely: 1. there is a rapid change in the world, driven by the technological revolution, which is clashing with established structures and with the way of life of societies and individuals; 2. This gap between the acceleration of technology and the slow pace of social adaptation to change is generating progressive crises in all fields and there is no reason to suppose that it will stop but, on the contrary, it will tend to increase; 3. the unexpectedness of events makes it impossible to foresee what direction events, the people around us and, in short, our own lives will take. It is not really the change itself that preoccupies us but the unpredictability that emerges from such change; and 4. many of the things we thought and believed no longer serve us, but neither are solutions in sight that come from a society, institutions and individuals suffering from the same malady.

On the one hand, we need references, but on the other hand we find the traditional references stifling and obsolete.

Similarly, he visualised the prevailing attitude of young people, with a description that, once again, fits what we continue to see, with very important implications for current social and political developments.

“I think it is time to say something that will be shocking to old sensibilities, namely: the new generations are not interested in the economic or social model that opinion-makers discuss every day as a central issue, but they expect institutions and leaders not to be just another charge to be added to this complicated world.

On the one hand, they expect a new alternative because the existing models seem exhausted and, on the other hand, they are not willing to follow approaches and leaderships that do not coincide with their sensibilities. This, for many, is considered irresponsible on the part of the younger generation, but I am not talking about responsibilities but about a type of sensitivity that must be taken seriously into account. And this is not a problem to be solved with opinion polls or surveys to find out in what new way society can be manipulated; this is a problem of global appreciation of the meaning of the concrete human being that has so far been summoned in theory and betrayed in practice”.

In relation to the non-fulfillment of the promises of leaderships and systems and in a clear signal about the subsequent appearance of opportunistic characters of easy and high-flown proclamation, Silo affirmed: “The crisis of credibility is also dangerous because it throws us helplessly into the arms of demagogy and the immediatist charisma of any leader of the occasion who exalts profound sentiments. But this, although I repeat it many times, is difficult to admit because it is hampered by our formation landscape in which facts are still confused with words that mention facts”.

After commenting on the need to revise the look from which events are analysed, tinged by landscapes formed in other eras, Silo synthesised in a few lines the main outlines of tendencies that continue to operate to this day:

“Our present situation of crisis does not refer to separate civilisations as could happen in other times when those units could interact ignoring or regulating factors. In the process of increasing globalisation we are undergoing, we must interpret the facts by acting in global and structural dynamics. However, we see that everything is becoming unstructured, that the national state is wounded by the blows dealt to it from below by localisms and from above by regionalisation and globalisation; that people, cultural codes, languages and goods are mixed up in a fantastic tower of Babel; that centralised companies are suffering the crisis of a flexibilisation that they are unable to put into practice; that generations are becoming isolated from each other, as if at the same time and place there were subcultures separated in their past and in their projects for the future; that family members, that co-workers, that political, labour and social organisations are experiencing the action of disintegrating centrifugal forces; that ideologies, taken over by this whirlwind, can neither provide a response nor inspire coherent action by human ensembles; that the old solidarity is disappearing in an increasingly dissolved social fabric and that, finally, the individual of today who has more people in his daily landscape and more means of communication than ever before, finds himself isolated and incommunicado. “

To which he then added:

“We are moving towards a planetary civilisation that will give itself a new organisation and a new scale of values and it is inevitable that it will do so starting from the most important issue of our time: knowing if we want to live and in what conditions we want to do so. The projects of greedy and temporarily powerful minority circles will certainly disregard this issue, which applies to every small, isolated and powerless human being, and will instead regard macro-social factors as decisive. However, in ignorance of the needs of the concrete and actual human being, they will be surprised in some cases by social despondency, in other cases by violent overflow and, in general, by the daily escape through all kinds of drugs, neuroses and suicide. In short, such dehumanised projects will get stuck in the process of implementation because twenty percent of the world’s population will not be able to sustain for much longer the progressive distance that separates them from the eighty percent of human beings in need of minimum living conditions.

As we all know, this syndrome will not disappear with the help of psychologists, drugs, sports and suggestions from opinion formers. Neither the powerful mass media nor the gigantic public spectacle will be able to convince us that we are ants or a mere statistical number, but they will succeed, on the other hand, in accentuating the sensation of the absurdity and meaninglessness of life”.

In a hopeful sense, Silo was then already expressing his conviction that “in the crisis of civilisation that we are suffering there are numerous positive factors that must be harnessed in the same way that we harness technology when it comes to health, education and the improvement of living conditions, even if we reject it if it is applied to destruction because it is diverted from the objective that brought it into being.

Events are contributing positively to a global review of everything we have believed up to now, to appreciate human history from a different perspective, to direct our projects toward a different image of the future, and to look at each other with new piety and tolerance. Then, a new Humanism will make its way through this labyrinth of History in which human beings have so often thought they had been annulled”.

Silo concluded that memorable address with phrases that still resonate today:

“I would like to end with a very personal consideration. In recent days I have had the opportunity to attend meetings and seminars with cultural personalities, scientists, and academics. In more than one case I seemed to sense a climate of pessimism as we exchanged ideas about the future in which we will live. On those occasions, I was not tempted to make naïve exaltations or declare my faith in a happy future. However, at this moment, I believe that we must make an effort to overcome this discouragement, remembering other moments of serious crisis that the human species has lived through and overcome.

In this sense, I would like to evoke those words, which I fully share, and which vibrate already in the origins of the Greek Tragedy: “…from all the paths, apparently closed, the human being has always found the way out”.