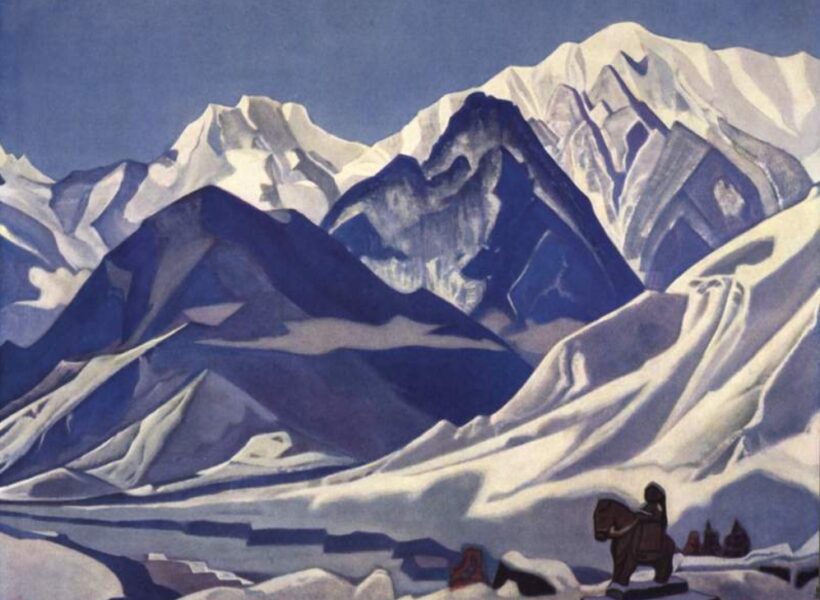

Looking around me, I observe people inside their oppressive thoughts, inside cars, walking in the city in a hurry towards inexcusable places. I stop and think of a great spiritual guide, who watches from the peaks of the Himalayas.

By Lucía Irurozki

Nikolai Konstantinovich Roerich (St. Petersburg, 1874 – Kulu, 1947). His surname is pronounced “Rérij”. He was much more than an excellent artist: a promoter of culture and peace, expeditionary, archaeological researcher, writer and public figure, he was in constant contact with intellectuals, scientists and artists of the Russian cultural scene of the time.

Together with his wife Helena, Roerich travelled all over Russia to contrast architectural styles with the historical context, producing more than seventy-five drawings. Immediately after, in 1904, Roerich painted his first religious work. His depictions are mainly based on saints and legends from Russia and the Slavic world.

If in his early paintings, colourful images of the folk epics of ancient Russia were his favourite subjects, from then on, the theme of India and the Orient became more and more prevalent in his canvases and literary works.

He painted more than 7000 canvases (many of which are in famous galleries all over the world) and wrote more than 30 literary works. He was the inspirer of the international agreement on the protection of artistic and scientific institutions and historical monuments (the so-called “Roerich Pact”), and the founder of the international movement for the protection of culture.

In 1899 Roerich met Elena (Helena) Ivanovna Shaphnikova, and in October 1901 they were married. Elena became Nikolai’s faithful and inseparable companion and his inspiration in adventure and spiritual work. They walked together throughout their lives, complementing each other in their creative and spiritual pursuits. In 1902 his son Yury, a future orientalist scientist, was born, and in 1904 his son Sviatoslav, who also became a renowned painter.

After completing his university thesis, Roerich planned a year-long trip to Europe to visit museums, exhibitions, workshops and salons in Paris and Berlin. Just before leaving he met Helena, daughter of the architect Shaposhnikov and niece of the composer Mussorgsky. There seems to have been an immediate mutual attraction, and they were immediately engaged. Helena Roerich was an exceptionally gifted woman, a talented pianist and the author of numerous books, including The Basics of Buddhism and a Russian translation of Helena Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine. Her epistolary, in two volumes, exemplifies the wisdom, spiritual insight, and simple advice she shared with a multitude of correspondents.

Continuing to work actively as a painter, Roerich in his last period also wrote large cycles of autobiographical essays “Diary Sheets” and “My Life”.

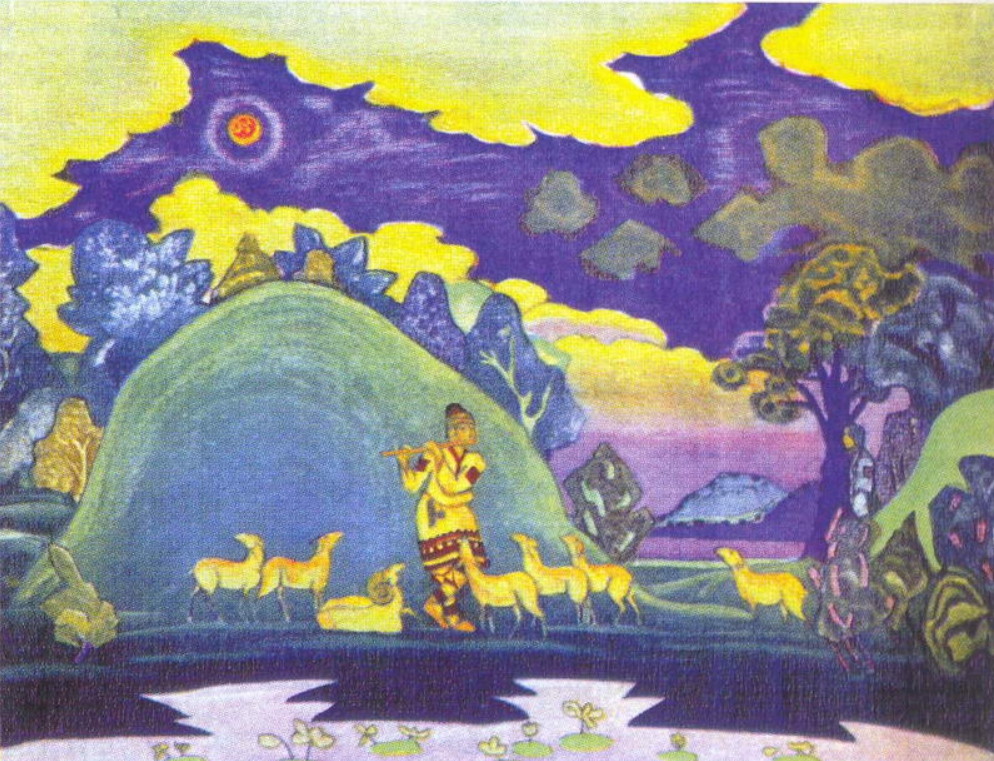

Roerich’s multifaceted talent was clearly manifested in his works for theatrical productions. During Diaghilev’s famous “Russian Seasons”, in the design of Nikolai, “Polovtsian Dances” from Borodin’s “Prince Igor”, “The Maid of Pskov” by Rimsky-Korsakov, the ballet “The Rite of Spring” with music. by Stravinsky took place.\

He is considered a master of Russian symbolism and an extraordinary figure on the cultural scene of his time. In 1915 he met the critic and historian Vladimir Stasov, through whom he came into contact with a number of composers and artists. He began to design sets and costumes for the theatre: he worked for Sergey Diaghilev’s ballet company and devised the sets for several operas at the Moscow Art Theatre. In 1920 he travelled to the United States thanks to the Art Institute of Chicago. The following year he set up the United Arts Institute.

Roerich, rebelling against academic mediocrity, instituted a system of art formation that seems revolutionary even by today’s standards: teaching all the arts – painting, music, singing, dance, theatre, and the so-called “industrial arts”, such as ceramics, porcelain painting, pottery and mechanical drawing – under one roof.

The cross-fertilisation of the arts that Roerich promoted was evidence of his inclination to harmonise, unite, and find correspondences between apparent conflicts or opposites in all ambits of life. This was a characteristic of his thinking, and one sees it demonstrated in all the disciplines he explored. In his own art he defied categorisation and created a unique and personal universe. In his writings on ethics, too, one can see that he constantly sought to connect ethical problems with scientific knowledge of the world.

Spiritual essence

Garabed Paelian states in his book Nicholas Roerich: “he learned things ignored by other men, perceived relations between apparently isolated phenomena, and unconsciously felt the presence of an unknown treasure”.

Culture in the Roerichs’ understanding, as the basis of the evolution of all peoples towards the Light, is a synthesis of the achievements of the creative thinking of all mankind, and above all, their desire to know the Truth in art, philosophy, science and religion.

In 1923, the Roerich family undertook an expedition to the East in order to study the customs, languages, religions and cultures of those regions. The journey lasted five years and took them to places such as Chinese Turkestan, Altai, Mongolia and Tibet. During this journey Roerich produced approximately 500 paintings reflecting the evolution of his philosophical concepts and his perception of the splendour of regions such as northern India. After the expedition the family settled permanently in the Kulu Valley, in the foothills of the Himalayas, in front of a breathtaking view.

Nikolai Roerich willed a treaty for the protection of the cultural heritage of peoples. The Roerich Pact stipulated that places of cultural importance, educational, artistic, scientific and religious centres should be respected and preserved, both in times of war and in times of peace.

The idea was supported by Romain Rolland, George Bernard Shaw, Rabindranath Tagore, Albert Einstein, Tomas Mann and other leading thinkers. The solemn signing of the Pact took place in Washington on 15 April 1935, with the participation of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and representatives of the 20 member countries of the Pan-American Union. Subsequently, 15 other countries signed the Pact. This treaty is still in force today and many individuals, groups and associations around the world continue to promote the Pact, the flag and its fundamental principles.

Nikolai Roerich continued until the no end of his life to live in the Himalayas, tirelessly painting the same ever-changing mountain panoramas in different lights, in an obsession that is related to the Monet of the Sainte-Victoire mountain but which is characterised above all by that transcendent dimension so consubstantial to Russian culture. The search for Shambhala, in the best tradition of Eastern wisdom, becomes its interior journey whose goal is self-knowledge and spiritual revelation.

In the essay Flowers of Morya Irina Corten writes: “the core of Roerich’s belief system is the Hindu concept of a universe without beginning or end, which manifests itself in recurring cycles of the creation and dissolution of material forms caused by the pulsation of divine energy. On the human plane, this means the rise and fall of civilisations and, in terms of individual life, the reincarnation of a soul…”

Roerich writes in the poem about the eternal:

Brother, let us abandon

the only thing that changes quickly.

Otherwise, we will not have time

to turn our thoughts

to that which does not change at all.

The eternal.