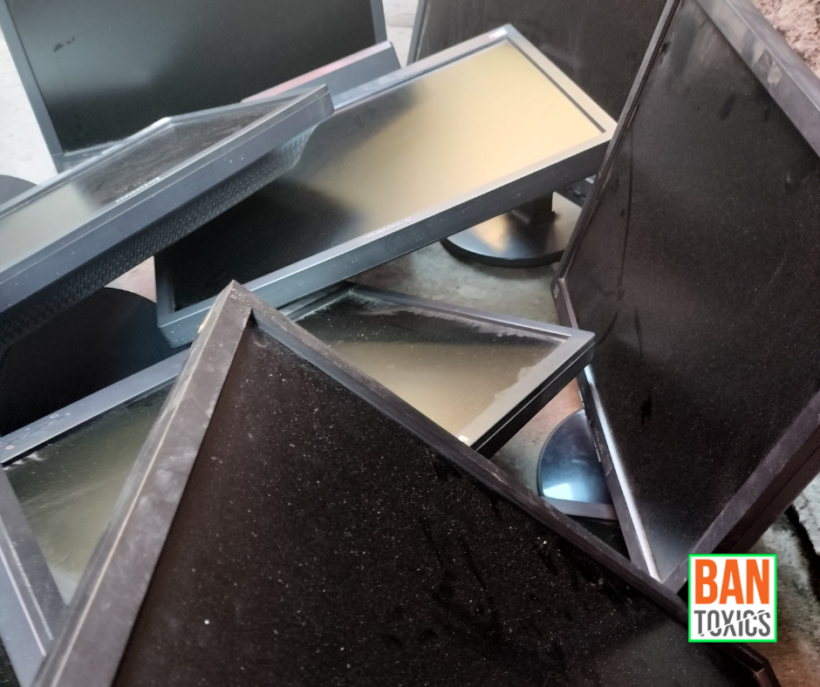

As the country celebrates Consumer Welfare Month and commemorates International Waste Pickers’ Day (held on March 1), BAN Toxics warns against the unsustainable production and consumption of disposable tech feeding the e-waste crisis, the fastest-growing waste stream.

“Annually, the world produces and consumes an enormous amount of electric and electronic equipment which results in millions of metric tons of e-waste, with only a small percentage being recycled. Industrialization, urbanization, and higher disposable incomes are major drivers of the waste of electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) or e-waste stream, posing major health hazards and environmental risks impacting the lives of people, especially in developing countries,” Jam Lorenzo, BAN Toxics Policy and Research Officer.

Flow Sources

The Philippines is among Southeast Asia’s top e-waste generators, with every Filipino generating an estimate of 3.9 kilos of disposed electric and electronic equipment (EEE) in 2019, according to the United Nations Global E-Waste Monitor. EMB-DENR reported that the country generated 32,664 metric tons of WEEE in the same year. The volume of waste mobile phones estimate in the country, for example, reached over 24 million units in 2021, based on a study published in Global Nest Journal.

E-wastes that contain toxic metals lead, cadmium, mercury, and hexavalent chromium, flame retardants like polybrominated biphenyls and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE), are regulated in the country under RA 6969, or the Toxic Substance and Hazardous Nuclear Waste Act of 1990. DENR Administrative Order 2013-22 guidelines were also released requiring generators, transporters, and treatment, storage, and disposal facilities of hazardous waste, including WEEE, to register with EMB.

“Aside from domestic streams, other sources of e-waste in the country include transboundary flows, and this is despite the Basel Convention. Data suggest that the majority of e-waste from developed countries in the form of used-EEE and surplus electronics are exported to developing countries for disposal which leaves the Philippines in a precarious situation,” Lorenzo said. The country is yet to ratify the Basel Ban Amendment to prohibit the illegal traffic of imported hazardous waste into the Philippines.

“Informal waste pickers who disassemble, refurbish, repair and resell used electronic devices, women and children, and the surrounding community are the most vulnerable to the toxicity of e-wastes because of environmentally unsound practices in collection and disassembly. BAN Toxics studies have documented some of the highly egregious practices including open burning of PVC-coated plastics, breaking and dumping of leader CRT glass, use of toxic acids on printed circuit boards, and the cutting and shredding of plastics coated with BFRs,” according to the group.

Sustainable Lifestyles

The environmental justice group promotes sustainable production and consumption to minimize the use of natural resources and limit unsustainable patterns that put pressure on our planetary boundaries.

BAN Toxics raises consumer awareness to promote more sustainable lifestyles and practices, which it believes should be mainstreamed in national laws and policies. “We need to look at gaps and barriers, build infrastructure and mechanisms, and encourage consumers to change their behaviors in their purchase, use, and disposal of electronics equipment,” Lorenzo said.

Lorenzo also emphasized the agency of informal waste pickers. “We must recognize the valuable participation of waste pickers as a critical stakeholder in waste management and promote their rights and protection. They must receive fair pay and compensation, provided with protective tools and equipment, be covered by health insurance, access to social protections, and be heard in decision-making and policy formulation.”

Industries and the public sector’s mechanisms for the collection and recycling of discarded equipment and compliance with the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) must be strengthened and made effective. Under the EPR Law of 2022, which extends the producers’ responsibility in managing the equipment after a product’s life cycle, large-scale companies are obliged to recover a percentage of their footprint.

Government agencies and local government units should formulate guidelines, regulations, and supportive mechanisms for the sustainable and sound management of e-waste.

References:

https://journal.gnest.org/sites/default/files/Submissions/gnest_02534/gnest_02534_published.pdf

https://ewastemonitor.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GEM_2020_def_july1_low.pdf

https://goodelectronics.org/vanishing-e-wastes-of-the-philippines-report-and-film-by-ban-toxics/