While the world seems to be heading towards a sharp economic slowdown, close to recessionary indicators, the arms industry is not slowing down its growth. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, global military spending set a new record of $2.1 trillion in 2021.

This figure meant that global arms sales increased for the seventh consecutive year and accounted for 2.2% of global GDP, with each country spending an average of 6% of total public expenditure on its military, SIPRI reported in December 2022.

This was already the case before the war in Eastern Europe, which has led to significantly higher military spending in 2022 by most Western countries.

Prior to the start of Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine (February 2022), NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg reported in June 2021 that eight allies (out of 30 that make up the militarist alliance) met the guideline of spending 2% of their GDP on defence, five more than in 2014. NATO’s total military spending in 2021 was then estimated to exceed $1 trillion.

Germany now plans to increase its military (misnamed ‘defence’) budget by almost 50 per cent, from 1.4 per cent of GDP to 2 per cent, similar to the increase announced by other NATO countries such as Spain and Poland. This indicates alignment with the requirements of the United States of America, the alliance’s extra-continental leader, to share spending more with European countries, reducing their share to close to 70 per cent of total spending.

Far from thinking about how to bring peace and demilitarise human coexistence on the planet closer together, the mentality continues to be one of “deterrence”, which implies a new round of arms “modernisation”, incorporating digitalisation and artificial intelligence into new weapons systems.

Major aerospace and weapons companies are accelerating the development of integrated and autonomous systems, precision-guided missiles and missile defence, cyber and digital capabilities, and hypersonic weapons.

This arms offensive combined with the predicted rise in unemployment and poor employment, worsening environmental conditions and the cruel and unconscionable concentration of wealth, coupled with ruthless competition for geopolitical power, portends a horizon of widespread global conflict.

Who profits from armed conflict?

Of the top ten companies in the global ranking of arms sales, five are American: Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon and General Dynamics. This is followed by BAE Systems, based in the UK, and then four Chinese corporations appear, with lesser-known names but climbing the destructive ladder: NORINCO, AVIC, CASC and CETC.

According to the figures available, these conglomerates had a turnover almost equivalent (46%) to the other 90 firms listed in the SIPRI top 100.

It is worth taking a closer look at who is making money out of such destruction.

In the US case, as expected, there are few surprises. The main shareholders of Lockheed Martin are three large investment funds, State Street Corp., Vanguard Group and Black Rock Inc. with a combined total of almost 30% of the shares. Another 45% is held by smaller institutional investors, with the remainder held in private shareholdings.

Boeing, on the other hand, is 57% owned by investment funds, the three most prominent of which, in addition to the aforementioned Vanguard and Black Rock, are the Newport Trust Co.

The third in the list of death producers is Northrop Grumman Corp, 85% of whose shares are controlled by investment funds, with SSgAFunds Management, Inc, Capital Research & Management Co and, once again, the Vanguard Group among the top three.

Something similar happens with Raytheon, where 4 out of 5 shares are held by funds, the first three shareholders being again the Vanguard Group, State Street Corp. and Black Rock.

The same ownership scheme is shown by General Dynamics, with 86% in the hands of institutional investors, among which Longview Asset Management LLC, Vanguard and Newport Trust Co. stand out.

The remaining shares of these companies are made up of investments by individuals in the stock market, generally mediated by advice and action from banks. A small portion (about 1%) is held by “insiders” – individuals who work in the same companies, usually in management positions.

Also, most of the shares of London-based BAE Systems are held by large mutual funds, the main ones being the Income Fund of America Inc, the Capital World Growth and Income Fund and the Capital Income Builder, Inc.

In the Chinese case, the ownership structure is different and the main companies, considered strategic, are wholly state-owned.

Norinco (China North Industries Group Corporation Limited), entered the core of the top five global arms vendors in 2022. It produces tanks and aircraft, heavy and light weapons, drones, artillery and a long list of death machines.

The Aviation Industrial Corporation of China (Avic) is one of the top ten companies in the country. Its production is highly diversified, but it has a strong focus on the manufacture of electronic technology. In 2022, it was the world’s second-largest arms contractor, with revenues equivalent to $79 billion, calculated in US currency.

The China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) is mainly engaged in the research, design, manufacture, testing and launch of space products such as launch vehicles, satellites, manned spacecraft, cargo spacecraft, deep space explorers and space stations, as well as strategic and tactical missile systems. Like the previous ones, it belongs to the State.

Finally, the tenth in the SIPRI ranking is CETC (China Electronics Technology Group Corporation), which is mostly involved in intelligence technology, including data processing, facial recognition, drone swarming, electronic parts and systems for radars, missiles, key components for satellites, among others.

For their part, Russia’s major arms-producing companies are grouped into the state-owned mega-conglomerate Rostec, officially the Rostec State Corporation for Assistance to the Development, Production and Export of Advanced Technology Industrial Products, founded in 2007. The organisation comprises some 700 companies, which together form 14 holding companies: eleven in the arms industry complex and three in civilian sectors.

What is driving the conflict and what can be expected in the future?

The report consulted [1] states that in 2021 there were active armed conflicts in at least 46 states (one less than in 2020): eight in the Americas, nine in Asia and Oceania, three in Europe, eight in the Middle East and North Africa and 18 in sub-Saharan Africa.

Added to this is the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, which at times threatens to escalate, as well as high tensions in the China Sea.

One of the main drivers of arms proliferation is the demand for markets and profits from arms companies. State capture by the arms conglomerate in the United States of America – the world’s largest exporter and consumer with a budget of more than $800 billion (38% of the global total) – is well known.

On the other hand, the relative decline of the once dominant power has unleashed a renewed arms race, attempting to stop the advance of economic competitors by threatening them, which in turn leads them to increase their arsenals.

But also, religious irrationalism, separatism, social exclusion of vast sectors, criminality, hatred as an ideological banner and the different repressive neo-obscurantism variants are on the rise in many countries, generating violence and more violence.

There are also glimmers of light in several places, with progress in peace agreements such as in Colombia, Yemen, Libya, Syria and Ethiopia. Encouraging are also the resolutions of blocs such as the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) with its declaration of a Zone of Peace in 2014.

Similarly, the increase in formal adherence to the binding Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, ratified by 68 countries, the consolidation of nuclear-weapon-free zones, the mediation efforts of the African Union, the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, the non-violent efforts in Burundi, Congo, Somalia, Central African Republic and South Sudan are some of the significant achievements.

There are also numerous disarmament initiatives in the United Nations, whose slow pace, coupled with blockage or lack of adherence or compliance by the main actors involved, diminishes their effectiveness.

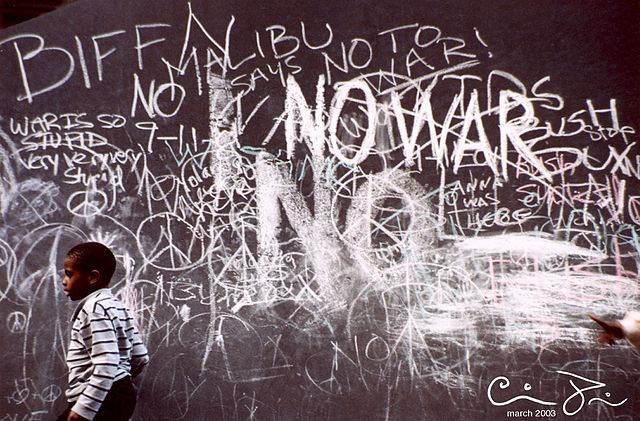

The current scenario leaves no room for doubt. We cannot wait, we must act decisively, turning the clamour for peace that exists among the peoples, the rejection of war, into a global wave.

In this sense, the points proclaimed by the First World March for Peace and Nonviolence, which travelled around the world between 2 October 2009 and 2 January 2010, promoted by the Humanist Movement and its founder Silo, are still valid.

“To avoid future nuclear catastrophe, we must overcome violence today, demanding the immediate withdrawal of invading troops from occupied territories, the progressive and proportional reduction of conventional weapons, the signing of non-aggression treaties between countries and the renunciation by governments of the use of war as a means of resolving conflicts.

In order to displace the influence of those prehistoric forces that hinder the emergence of the world of the future, it is necessary to go even further and embrace non-violence as an attitude of daily and permanent life.

Such a world, such an attitude can and must be born in every human being and expanded through collective action. Its time is today.

[1] SIPRI Yearbook 2022, English summary. https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/yb22_summary_esp.pdf