I belong to a privileged generation. I was born in the late 1960s in Kiev, the capital of a Soviet and socialist Ukraine, and I had the good fortune to spend my childhood, adolescence and even my youth in a country demonised like no other in the history of mankind: the USSR.

A huge memory, which we will have to rescue from oblivion. Not for museums, but as material for the new scaffolding of the times to come. It is an immense task that has yet to be done.

Talking in Havana with Che’s eldest son, Camilo Guevara, a great human being who passed away a few months ago, when we were trying to analyse the role of the Soviet Union in world history, he said to me:

“(…) We are talking about a great nation that developed an autochthonous and epic revolution against all odds. It defeated the Nazi-fascist hordes at the cost of the sacrifice of its people, doing humanity a priceless favour. The Soviets performed feats of various kinds and in countless fields. I am one of those who believe that not even the most objective or visceral critics or enemies of the USSR expected such a thing. I was always convinced that there was no force capable of destroying such an enormous work. I underestimated the political bureaucracy, the accumulation of mistakes and the capitalist influence on the mentality of some leaders (…) I believe that it is still necessary to make an analysis as scientific as possible. That is to say, stripped of any hint of sentimentality or ideological affinity in order to arrive at a more or less precise result. I am not advocating that this issue be approached without militant or class perspectives, that is impossible, I only ask that it be seen as an experience that must be stripped bare, x-rayed, auscultating every last insignificant bit to discover the roots of what was wrong or right, because that experience is, perhaps, in an improved version, the only way that exists to save us as a species…”.

The worst crime the USSR committed, the one for which it will never be forgiven, was to have been a shared hope for a more just, more dignified and more humane society. This is what the Soviet Union gave not only to its inhabitants, but to all the peoples of the world without exception. Since the triumph of the Bolshevik Revolution in faraway, exotic Russia, the world has never been the same. The power of the soviets (people’s councils) challenged that previous order established from above to crush those below, an order which until then had seemed immutable.

In the Soviet Union we learned as children that happiness in life was to help others and that our destiny was to know the Universe without limits. All we had to do was to study and learn a lot, to be good companions, to become people worthy of our parents and grandparents. We had totally free health and education services; even more: at university, for good marks, the state paid us. We read a lot and watched a lot of films.

We dreamt of travelling the world, making friends from all countries, cultures and colours. We felt that the future was ours, that it was within reach of our years, and that it would be up to our generation to end wars and unite the peoples of the world, finding cures for diseases and putting an end to injustice and the exploitation of man by man in human history. To dream of having a lot of money was frowned upon.

We believed profoundly in romantic, modest, innocent love and selfless friendship as supreme values. We had nothing to spare, for we had no luxuries, no big houses, no trips abroad. Nor did we meet our friends in cafés or restaurants, but in our homes, where we shared the little and the many things we had. We knew literature, music and cinema from all over the world and never tired of talking and wanting to know more. When someone got sick, doctors came to visit them at home free of charge. Women retired at 55 and men at 60. We had constitutional rights, such as free health, education and housing, which were strictly enforced.

If we were to recount all this today, many people in most countries would tell us that it is a propagandistic exaggeration or a nostalgic old man’s delirium, that it is a lie because real life is no longer like that and all these things could never be true or possible. Others, more informed, will have their thousand buts ready, recalling the absurdities of bureaucracy, Stalin’s political repressions, the multiple forms of citizen non-freedom, the difficulties in going abroad, the huge queues and shortages of goods in the shops, the censorship and the great distance between official discourse and private conversations. It would also be true, but one of those which, without context or nuance, comes closest to being a lie.

It is very difficult to talk about the Soviet Union from the realm of the secondary, so normalised and generalised by capitalism, where the freedom to choose between a thousand colours and textures of toilet paper is something that is so brazenly presented as one of the steps towards full happiness. Those who never knew how to dream of anything outside their personal well-being have no way of understanding the achievements and failures of the Soviet project, not because anything is bad or good, but because of the incomparable dimensions, levels and sizes.

The USSR was the first and most convincing proof that a long existence of a society where money is neither the central value nor the main condition for human development is possible. Yes, money was very important in the Soviet Union. But it was not everything, and I think that this is precisely its main difference from Western societies.

It is not true that the USSR was destroyed because of its economic inability to compete with the West. Nor is it true that its fall was the result of long or clever work by enemy intelligence services.

The Soviet Union did not cease to exist because of an external political enemy; what destroyed it was its own lack of democracy and real participation of citizens in state decision-making, together with the naivety and political childishness of its people, who failed to value and defend their enormous social gains.

The new generation of opportunist bureaucrats in power, who massively permeated the state, understood that capitalism suited them much better and, taking advantage of the people’s lack of political experience since the times of Gorbachev, unleashed a tremendous anti-communist political campaign that has not stopped to this day, and then, led by Yeltsin, staged a right-wing coup d’état. We understood everything except politics. We didn’t realise it.

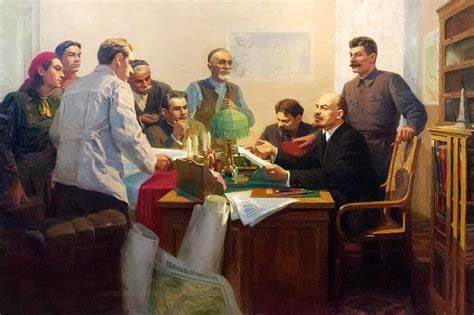

Decades passed… and while in some ex-Soviet republics hordes of ignoramuses encouraged by the power and its press are still destroying the last monuments to Lenin, going on to desecrate the graves and memorials of anti-fascist soldiers, in other cities the towns are scraping together the money to put up statues of Joseph Stalin again. We will not discuss now how bad or how slandered this personage has been, let’s leave that for better times, but this particular fact tells us that people feel an enormous need to hold on to their historical memory, where that project with its lights and shadows opened a future for all of us, made us dream of a different world, when the word ‘future’ did not arouse fear, but hope and longing.

With the tragic experiences of this new millennium, we learned that time is reversible. The people of today simply do not find ideologies and hope in other visions of ‘progress’.

Any minimally serious historical analysis makes us think again of the greatness of a people who were able to create another type of economy and to leave the cultural domain of others and create their own, another aesthetic, spiritual, ethical project, an indelible memory that today gives us wings to know that it can be done again, even if it is not the same… because, as the song ‘Todo Cambia’ says, “And what changed yesterday, will have to change tomorrow”. Because everything that was criticised about the USSR, including the worst mistakes and unresolved problems of ‘real socialism’, are today the constant in the society we live in, only they are magnified and multiplied many times over by the degeneration of the modern neoliberal capitalist world.

If in the USSR many things worked badly, in the present system practically nothing works, only if they are business for the very few, in the very short term and at the cost of everything. Speaking of Soviet ‘concentration camps’ or prisons, today’s pseudo-democracies everywhere multiply thousands and thousands of others, of all kinds, visible and invisible, much worse than those of that time.

And the dangerous nostalgia for the USSR increasingly resembles a nostalgia for the future.