In the shattered and unhinged context in which we find ourselves living, reading Alessandra Bocchetti’s latest book Basta lacrime (VandA. editions, 2022) offers women and men, girls and boys-interested in reading the lesser-known side of the origins of the ongoing unhinging and openings on ideas and visions in a horizon of authentic freedom thanks to the power of a subversive idea of the millenary order of patriarchy-a chance to retrace , if not to discover, the political history of Italy in the twenty-five-year period 1995-2020 through the gaze of a woman committed together with other women to the building of a civilization that puts in the first place a new sense of humans addressed to the care of the living, to maternal attention, to the tension toward justice.

By Maria Concetta Sala

It is a political history that continues to nurture “ordering principles of society” totally different from the dominant ones – such as power, money, violence – and that contributes to the spread of “a less heroic, less violent, more grounded culture in the world” (p. 287), because it is anchored in the knowledge and acceptance of human frailty and the condition of interdependence to which we all, women and men, are subjected. It is an extraordinary reinvention of being in the world starting from the “hidden work” of women, “in short, the invisible of history,” which is “today, a treasure accumulated over centuries [for us] to spend, which is their material knowledge generated by having always seen humanity very closely, in its splendor and in its misery, in its perfumes and in its stenches” (p. 78).

To the feminist of difference Alessandra Bocchetti, a leading figure of the Virginia Woolf Cultural Center in Rome, founded in 1979 together with other friends, to the woman who has always been in dialogue with institutions but distant from institutional or state feminism, we owe this collection of political writings that, although precisely dated in that 20-year period, revolve around issues that are still decisive for the future of all humanity and urge further debate – I list a few: Violence and identity, body and motherhood, violence and justice, rights and desires, freedom and liberation, feminism and feminisms, subjectivity and women’s government… Complex issues that Bocchetti’s documents, letters, and articles have the merit of posing with great calmness and formulating in a flat, fluent and clear register.

I will dwell on some aspects that are to some extent surprising and that most aroused my curiosity and stimulated interest, first of all the resurfacing in several writings of a word such as ” human dignity,” which I would like to reinterpret bearing in mind the possibility of establishing links with a woman’s pursuit of happiness.

Dignity is a little word that has a long history: it concerns the unique and unrepeatable value that each individual male or female possesses per se as a human being existing on this earth, in his or her quality as a human being, in his or her being a participant in the common humanity. Simone Weil, much beloved by Alessandra Bocchetti, and whose thoughts recur frequently in this collection, is the first to make the affirmation of human dignity an unconditional obligation, the primary obligation, hooking it to human needs, to the nourishment of the body and soul of every human being:

The object of obligation, in the realm of human affairs, is always the human being as such. There is obligation to every human being, by the mere fact that he is a human being, without any other condition having to intervene; and even when none is acknowledged to him.

This obligation is not based on any factual situation, neither on jurisprudence, nor on customs, nor on social structure, nor on power relations, nor on the legacy of the past, nor on the supposed orientation of history. For no factual situation can elicit an obligation.

This obligation is not based on any convention. For all conventions are modifiable according to the will of the contracting parties, while in [this obligation] no change in the will of human beings can alter anything (1) .

It is, Simone Weil continues, a fundamental, eternal, unconditional obligation, which “has no foundation but an acknowledgement in the agreement of universal consciousness” (2) and is found expressed in the most ancient texts from ancient Egypt onward.

For Alessandra Bocchetti dignity is a great word: ” On second thought, it alone would be enough to make a good government program. If one thought about the dignity owed to each human being in this land, what wonderful programs would be made for jobs, for education, for health! Yes, dignity is a word that helps us do the right thing” (p. 224). Human beings, women and men, Bocchetti rightly argues, are equal solely in dignity, which “is not a good to be conquered but which each has, in spite of himself or herself, by the mere fact of being born, by the mere fact of sharing the human condition. I would like to read in courtrooms the words in plain sight, ‘Dignity is in each of us;’ [this] would perhaps be a profoundly truer phrase than ‘Justice is equal for all'” (p. 245).

Recognition of human dignity, we know, is a pillar of legal civilization and of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights approved in 1948 by the United Nations General Assembly, and we also know what and how many struggles women have had to endure in order for this principle to be translated into de facto reality, but, Bocchetti vigorously emphasizes, all that women have won on paper, in rights, ” can remain a dead letter if it is not animated by a breath [… ] that gives energy,” and this breath ” is precisely a new and strong idea, capable of changing the rules of the game. […] It is the idea of entitlement-expectation of happiness. You see, I used a double word, “entitlement-expectation;” actually neither one nor the other is good, the word entitlement is too arrogant, the word expectation is too weak. It would take a third one…” (p. 81).

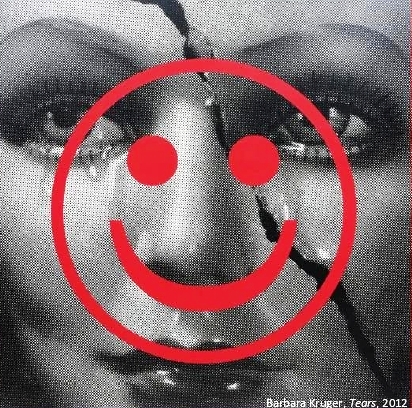

It is wisely pointed out in another paper that this is a new idea, an extraordinary and revolutionary achievement, because it has triggered a change in the order of discourse and the order of facts, but here and there the impatience of “all and now” surfaces, which is in my opinion a mistake, because the women’s revolution is a symbolic revolution, which includes action and contemplation, and it needs a very long time. And for that matter, Bocchetti herself admits this in her speech during a conference on the 1970s held in Cinisi in 2018: ” A woman’s happiness always gave a certain scandal in the order of the fathers, it always turned out to be a little out of place; pain was the feeling that best suited the woman, her icon. Now, however, this possible happiness is in the heads of all of us” (p. 239); and this “was a great step forward toward freedom” (p. 247), she reiterates in a speech given at the conference “Stereotypes and Prejudices on Gender Violence” organized by the Democratic Area for Justice in the Senate in 2019.

Another important aspect of this book is the prominence given to women’s work, that in the home, that outside the home, right up to the justifiably uncompromising stance against that terrible contract that regulates motherhood for others. Bocchetti is aware of the static view of women’s freedom that mainstream politics has made its own and denounces double-edged weapons such as, for example, parental leave and part time, which keep women captive and protected in cages; and she speaks out against gender policies that have reinforced rather than eroded women’s misery and weakness in a sincere self-criticism that is something rare and exemplary in the history of the women’s movement: “We have given credit only to women’s misery, to their weakness, and have tried to devise policies of protection, of shelter, of consolation, not realizing that, in so doing, we contribute to our imperfect citizenship. […] Our citizenship becomes full only when our attention and modifying tension go to society [and are] understood in their complexity, ” because women are “a constituent part of society itself” (pp. 152-53). Her reflection on the formula “labor-power” is still fundamental today : ” Factory masters do not buy the workers, they buy their ‘labor-power.’ The workers do not sell their bodies, they sell their “labor-power.” Simone Weil and others explained this pure deception to us. Weil, who wanted to experience the assembly line at Renault, tells us that it is the whole life that goes away, gone is the ability to think, the ability to imagine, the will to speak, health, eros…” (pp. 217-18).

Alessandra Bocchetti does well to emphasize the importance that a women’s reflection on work could have today: ” No one has ever really defended women’s work, neither the parties nor the unions. Women’s work has always been considered additional. […] It is important for feminism to take on this issue at this time, it is an issue at the same time material and deeply symbolic ” (article that appeared on July 20, 2020, in the 27th-hour supplement of “Corriere della Sera”). I agree, we need to pick up the threads of the discourse starting with the 2009 “Underbelly”. Imagine that Work, a manifesto well summarized in the formula Primum vivere (First live), which means putting life at the center but not by subordinating the material experience of living to theoretical reflections on living or vice versa, but rather by valuing what makes life worth living, what is vital and not deadly (3).

1) Simone Weil, La prima radice. Preludio ad una dichiarazione dei doveri verso l’essere umano, trad. di Franco Fortini, SE, Milano, 1990, p. 14.(The first root. Prelude to a declaration of duties towards the human being)

2) Ibid., p. 15.

3) In this regard, see further considerations in the article written for «pressenza. International Press Agency, Redazione di Palermo: https://www.pressenza.com/it/2020/11/tutto-il-lavoro-indispensabile-alla-vita/