Racism and discrimination against children on the basis of their ethnicity, language and religion remain widespread in many countries around the world, according to a UNICEF study released on World Children’s Day, 20 November.

On World Children’s Day, and every day, all children have the right to feel included, to be protected and to have equal opportunities to reach their full potential,” said Catherine Russell, director-general of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), in launching the report.

The document, ‘Denial of Rights: The Impact of Discrimination on Children’, shows how racism and discrimination affect education, health, and access to birth registration and a fair and equitable justice system.

It also highlights the wide disparities that exist between ethnic groups and minorities, not only in wealthy privileged countries but also in many poor and developing nations.

Among its findings, the report reveals that children aged seven to 14 from marginalised ethno-linguistic and religious groups in 22 low- and middle-income countries lag far behind the rest in reading skills.

For example, in the Central African Republic, the Gambia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sierra Leone, the reading skills of the most advantaged ethnic group are four times higher than those of the most disadvantaged ethnic group, and double in countries such as Bangladesh, Macedonia, Mongolia, Suriname and Vietnam.

Similar differences were found when analysing the cases of the most and least advantaged linguistic and religious groups in the countries studied.

An analysis of data on the number of children registered at birth – a prerequisite for access to basic rights – revealed significant disparities between religious and ethnic groups.

In Laos, for example, 59% of children under the age of five from the Mon-Khmer minority ethnic group are registered at birth, compared to 80% of those from the Lao-Tai ethnic group. In Zimbabwe, children from Christian families had a higher rate of such registrations than those from traditional or non-religious families.

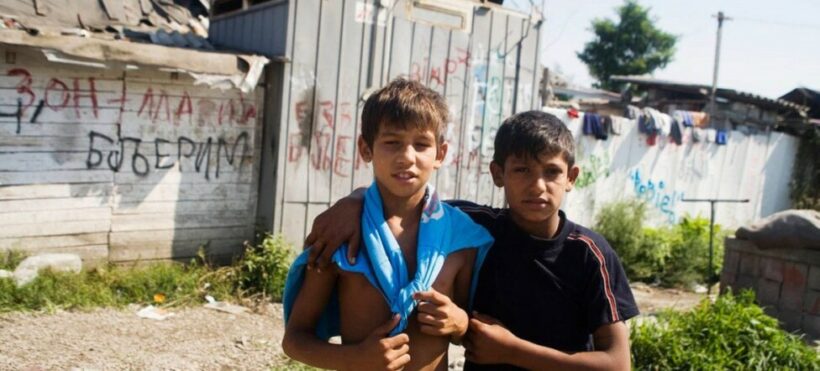

The 12 million Roma are the largest minority ethnic group in Europe, spread across many countries, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, and their children are among the most discriminated against, with high rates of poverty, poor job prospects and little support and access to social services.

High out-of-school rates were also found in these countries, as high as six per cent in some countries and more than 20 per cent in Kosovo, North Macedonia and Montenegro. This situation is compounded by an increase in child marriages, which curtails educational opportunities, especially for girls.

UNICEF shows that also in the area of health, such as access to vaccines, water and sanitation services, discrimination and exclusion have persisted for millions of children from ethnic and minority groups.

A study in 64 countries found that in more than half of them, vaccination rates for children from ethnic minority groups were lower, with five countries showing a gap of 50 percentage points or more.

In terms of disciplinary policies, the report showed that in the United States black children and young people are almost four times more likely than white children to be temporarily expelled from school, and more than twice as likely to be arrested for incidents in the school environment.

In the UK, Black, Asian and minority ethnic children are over-represented at almost every level of the UK criminal justice system. In England and Wales, Black children are four times more likely to be arrested than white children.

The analysis stresses that discrimination and exclusion exacerbate intergenerational deprivation and poverty, and have serious consequences for children’s health, nutrition and education.

In addition, children who experience discrimination and exclusion are more likely to be incarcerated, to have higher rates of teenage pregnancy, and to have lower incomes and fewer employment opportunities in adulthood.

According to a UNICEF U-Report survey of 407,000 people, almost two-thirds of them perceived discrimination as common in their environment, and almost half believe that such practices have had a significant impact on their life or the life of someone they know.

“Experiencing exclusion and discrimination in childhood can have lifelong consequences. It hurts us all. And we all have the power to fight discrimination against children – in our countries, communities, schools, homes and in our own hearts,” Russell concluded.