Written from the perspective of a journalist who covered wars for 30 years in Latin America, the Balkans, the Middle East and Asia, the book “Truth is Bombed. Media and War through the eyes of a war correspondent” is an experiential narrative with a strong reflective tone, which applies for the first time in the science of communication in Greece the method of auto-ethnography and at the same time the result of a long-term research effort to document the role of powerful news organizations in the coverage of armed conflicts, fake news, propaganda and censorship in the major wars that shook the world from the 19th to the 21st century.

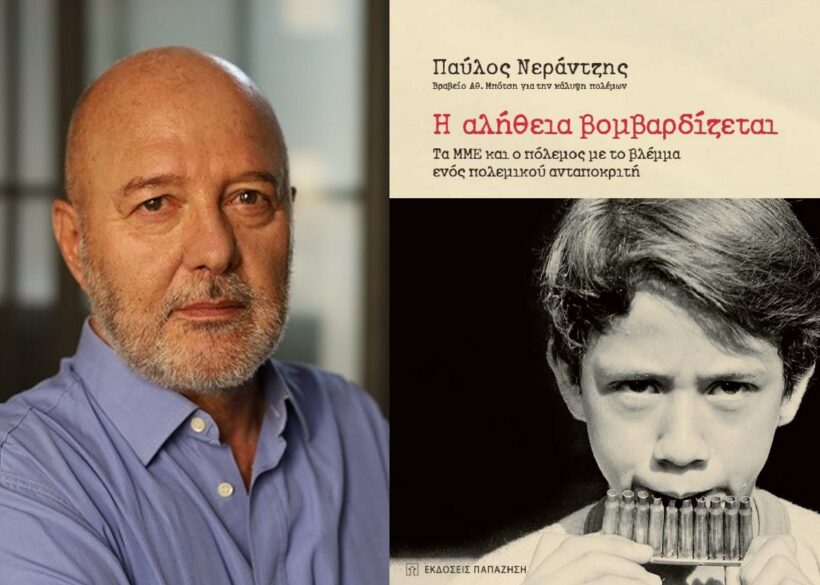

On the occasion of the publication of his book, the author, journalist, documentary producer, doctor of the Department of Journalism & Media of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and research associate of Institute for Alternative Politics – ENA, Pavlos Nerantzis talks to the Head of Communication & Media of the Institute, Vangelis Vitzilaios.

We are seeing significant changes in the form and practices of warfare in the last century compared to the 21st century, with the “postmodern wars” you mention in the book having a significant impact on the communication sector. Would you like to explain what you mean?

In postmodern armed conflicts, since the Gulf War, there has been a rapid shift in the centre of gravity from the power of weapons to the power of information. Owing to technological developments and the involvement of private corporations, the form of warfare has changed. Elites have formulated new communication strategies, promoted media centralization and sensationalist journalism, as well as ‘recycling journalism’. All this has been reinforced, resulting in new standards in the coverage and representation of war.

In other words, in the era of neoliberalism, these new facts are the result of the strengthening of the so-called military-industrial-media complex, i.e. the interlocking of political and military power, war industries and press barons at the expense of the credibility of the media.

For those of us who have been in war zones since the 80s, these changes were quickly felt in the field: first in the Operation Desert Storm and in the wars in the Balkans, and then in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The main features were, on one hand, the integration of embedded journalists into the armed forces of the belligerents, in order to have greater control over the flow of information, and, on the other hand, the strengthening of propaganda mechanisms, thanks to the collaboration between the military and PR companies offering ready-made reports. It is no coincidence that the propaganda discourse is increasingly seen as the one and only truth, while journalists who have a critical approach and investigate in search of the truth find themselves targeted, persecuted, discredited or even murdered. This is demonstrated, moreover, by the rapid increase in the number of war correspondents who have lost their lives in the last twenty years.

In short, while direct links to the battlefields have brought war into households and conflict has become a spectacle, the information is poor and sterile. For example, the mainstream media reproduce the discourse of political power about “humanitarian wars”, “smart weapons” and “collateral damage”, when in fact in postmodern wars the number of civilians who lose their lives has multiplied in comparison to that of the armed combatants.

Despite these changes, are there, however, constants in the relationship of media and journalists to the war?

Of course there are constants. As I mention in the introduction to the book, once a journalist is called upon to gather information about a major event such as an armed conflict, he or she is essentially making history, it becomes the moment history is made. The journalist is certainly not a historian, but he or she is de facto required to capture and convey to the public in words and images what is happening, at the moment it is happening.

Reporting from war zones is the first attempt to record history in real time. And, as Robert McNamara, Secretary of Defense during the Nixon administration, said, “attempting to make history out of contemporary events is a high-risk exercise.”

The question is in an armed conflict how will the war correspondent report as many sides of the truth as possible while his life is at stake, while the combatants spread fake news and impose censorship measures, while the media compete with each other. How in the extreme circumstances of an armed conflict, in which he is not fighting for his own survival like the others, he must remain safe and, as an eyewitness, recount moments of death, untold misery and diplomatic manipulations on which the lives of thousands of people depend. That is why, from the time of the Crimean War to the Vietnam War and the Lebanese Civil War, from Russell and Hemingway to Fallaci, Page, Leroy and Fisk, the role of the war correspondent has dominated the coverage of a conflict. It was an almost mythical figure in popular narratives. That is now tending to change.

The second constant in the field of communication in a war is the attitude of the combatants. Political and military leaders have always attempted to misinform their opponentsin order to hide the wrongs, fabricate social consensus and keep the morale high. Misinformation is easy to document in retrospect, but very difficult to detect in the moment it diffuses into a foggy landscape.

Truth is the first casualty of war. The truth – or rather aspects of the truth – are suppressed or distorted because of propaganda and censorship. “If people really knew [the truth], the war would stop tomorrow,” British Prime Minister Lloyd George told the editor of the Manchester Guardian during the Great War.

In the age of post-truth, fake news and “recycling journalism”, can the journalist bring out the truth? Or is the degradation of the role of the war correspondent in postmodern wars irreversible?

Some believe that the role of the war correspondent, due to the conditions in the field I mentioned above, has been eliminated. On the contrary, I believe – and this is what I attempt to demonstrate in the book, after tracing the emergence of the first war correspondent – that the presence of the journalist in a war zone is as necessary as ever. As long as he/she has certain tools to hand, he can gain credibility and minimise the risk of being transformed into an uncritical relayer of propaganda messages.

Does the subjective factor, emotionalism and experiences in the war zone “cloud” the war correspondent’s cool eye in recording events?

I devote many pages of the book to this topic, because it haunts me every time I am in a war zone. It is a difficult balance that is not a foregone conclusion. All the more so because each of us has a different ideology and psyche, as well as different motivations that lead us into a highly toxic environment. Do not forget, moreover, that language is an ideological tool. It is no coincidence that some war correspondents emphasise in their reports the power of weapons, heroism, using diatribe, while others describe human suffering and refugeeism and seek the real causes that led to an armed conflict.

From the time of World War I and the Spanish Civil War to the present day, two schools of thought have been recorded in the journalistic community. According to the first, journalists must describe a war situation “objectively”, while according to the second, objectivity is a myth and the goal of a war correspondent is to illuminate as many aspects of the truth as possible, mainly highlighting the dark side of developments. In my opinion, the former usually stay on the surface of things, champion the ‘day side’ and reproduce the propaganda discourse. There are, of course, those who apply the rules of sensationalist journalism, of yellow journalism, in order to arouse the public’s anger and increase readership or viewing figures.

The first school of thought is dominated by “who did something, when and what” and rally around the flag. The second school of thought is dominated by “why something happened”. That’s why those who follow it are suspicious of even the propaganda of the day side. It is a conflict between two schools, one of supposed impartiality and the other of honest bias.

Obviously I place myself in the second school of thought. Because war not only destroys material goods and leads to the death of human beings, it does not only subvert normality, but it is against democracy. For the same reason I wrote this book at a time when the media can ultimately be a key factor in the outcome of a war. This is a book that appeals to the academic community as well as to the common man.

I believe that understanding the root causes of postmodern conflicts and their consequences – and it is the duty of the war correspondent to contribute to this – will most likely prevent public opinion from acquiescing to the legitimization of barbarism, the normalization of resorting to armed violence and experiencing the nightmare of another war. Not to say that one did not know what was happening where human life loses its value, as I note at the end of the book.

The book “Truth is Bombed. Media and War through the eyes of a war correspondent” is written from the perspective of a journalist who covered wars for 30 years in Latin America, the Balkans, the Middle East and Asia.

It is an experiential narrative with a strong reflective tone. Applying for the first time in the science of communication in Greece the method of auto-ethnography it is the result of a long-term research effort to document the role of powerful news organizations in the coverage of armed conflicts. In particular it focuses on fake news, propaganda and censorship in the reporting of major wars that shook the world in the 19th to the 21st century.