The condition of origin

In Chile, democracy and its political system is based, beyond any minimally logical foundation, on a model of political parties, which has no basis for its functioning, evaluation and necessary improvement in a changing world.

This situation has to be understood, starting with the fact that its design came from the hands of a civil-military dictatorship, with a marked intention to make an apology for the depoliticisation of the citizenry, using all its power to generate this condition, from terror, to the dismantling of the educational system and a constitution imposed with countless anti-democratic articles, which were gradually ironed out in the recent decades with reforms, which, however, did not make it lose its anti-democratic essence.

Basically, the parties in Chile for a long time were not financed by the state, and this led to the domination of the business community, who financed them, regardless of their ideological denomination, in exchange for laws that only perpetuate their economic and social privileges. This was a breeding ground for unlimited political and corporate corruption, with impunity in the dismissal of cases by the Public Prosecutor’s Office (whose highest authority is, precisely, elected by that same political power).

Among the reforms that the Chilean political model has undergone, those carried out in 2016 stand out, such as law 20900, which substantially modifies the rules on financing of political parties and Law 20915, which transforms the legal nature of political parties.

The amendments made in 2016 include article 56, which establishes minimum voting and representation requirements for a party to remain legal: “a party will lose its legality if it does not obtain 5% of the votes in the last election or if it fails to elect four parliamentarians in eight regions, in three contiguous regions or in two different regions”.

We consider that this model thus legalises the exclusion of parties, in a discriminatory act as it does not value the election of local power positions, nor does it allow the expression of ideological diversity, it is antidemocratic, as it does not reflect the real representativeness of the whole of society and it also undermines the freedom of political law, and therefore, it is urgent to review and modify it.

The consequences of the course of national politics

In the case of the Chilean Congress, the latest CEP survey of April-May of this year indicates that citizens’ confidence in the Senate stands at 10%, and the Chamber of Deputies obtains

10% of the population. Even lower still are the political parties, which have only 4% of the population’s confidence.

In these decades, as described, the essence of militancy and political mystique ends up broken. Numerous examples of resignations, break-ups, changes of party, accommodations, and resolutions that make people move from one political tent to another are daily news.

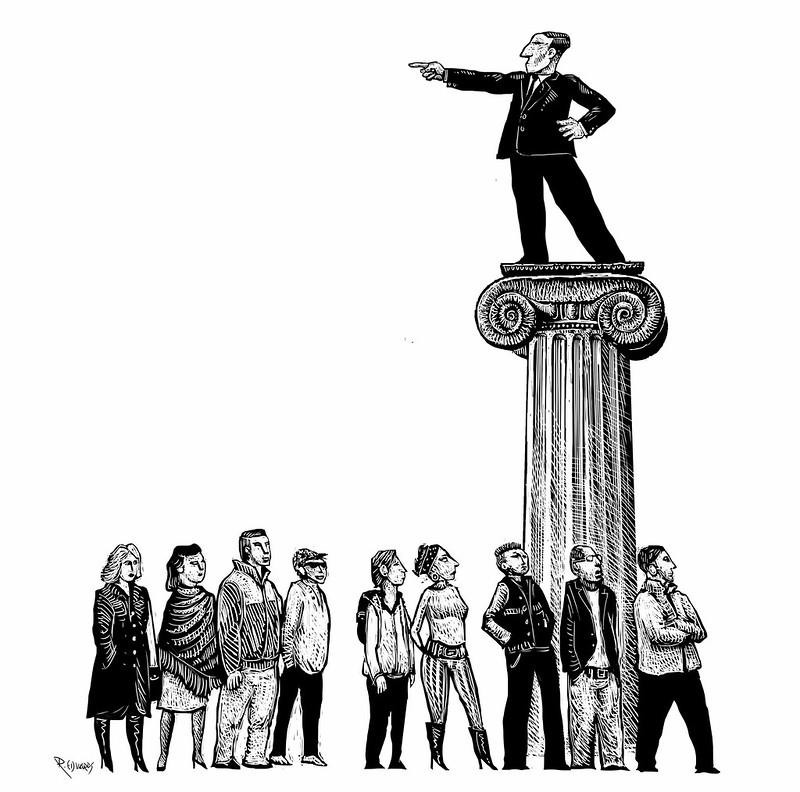

Some politicians have been installed in a real exercise and professionalism to change seats and membership of a militancy equis, as in the game of musical chairs, forgetting their origins, ideological foundations, seeking to reach a position in the elite of political power.

This ideological inconsistency, which seeks nothing more than personal power, confuses a citizenry already stripped of their valuable civic education, who recognise repetitive faces, without going beyond the knowledge of the political proposals presented and from which ideology they are being raised, in a politics of marketing and show business.

A parliament under these conditions, which also combines, on the one hand, the impossibility of carrying out public policies that involve state funding (which are those that are urgently needed in the social base); and on the other, the autonomy of the elected representatives that legally prevents them from answering to their parties in their actions, ends up degrading politics, weakening the parties to the maximum, and allowing a scandalous spectacle, inoperative to positively modify the inhuman conditions in which the majority of the country’s people live.

The costs of political transformationism in terms of pain and suffering for the citizenry

Everything described above would be no more than a bad joke, were it not for the fact that such parliamentary inoperativeness perpetuates an unbearable condition for the majority of salaried, unemployed, retired and children and adolescents in Chile.

To give concrete examples, the number of encampments increased when Chile’s macroeconomic indices grew the most.

According to the analysis of the Ministry of Housing’s cadastre, camps are characterised as “preferably urban settlements of 8 or more households living in irregular possession of land, lacking at least 1 of the 3 basic services (electricity, drinking water and sewage system) and whose dwellings are precarious, grouped and contiguous”.

The study also gives a breakdown of camps by region. It reveals that the region with the most camps is the Valparaíso region (255), followed by the Biobío region (156), the Metropolitan region (142), the Atacama region (106) and the Antofagasta region (85). It also states that 51 per cent of the inhabitants in these households are women and 36 per cent are migrants.

Another sign of this dire condition are the indices that reveal an accelerated deterioration of employability. The Comprehensive Unemployment Rate for the quarter June-August 2022

stood at 10.9%, corresponding to 10.2% for men and 11.7% for women.

Fundación SOL affirms that structural problems in employment persist, an example of which is the Labour Force Underutilisation Rate (SU4), which reached 19.6%, or 2,055,733 people. This indicator reflects the percentage of people with partial, total or potential unemployment and shows the pressure on the “labour market”, as it includes those who declared availability and the possibility of starting a job soon.

The only possible response is to organise in the territories, the convergence of the good people in the construction of a political social force that aspires to take over local power, to displace the elite with a project for a country that emerges from the grassroots. This is the challenge and the hope of the people of Chile.

Collaborative writing by M. Angélica Alvear; Gladys Mendoza; Guillermo Garcés; César Anguita and Natalia Ibáñez. Political Commission