The work of Cecilia Vicuña (1948 Santiago de Chile) has remained on the margins of public visibility for around 40 years. It wasn’t until a decade ago that some art curators began to take notice of her work to remove it from the margins, from the failures to the light. The artist, a petite woman, fragile in appearance but worthy of admiration for her great strength, tenacity, constant work and an admirable social discourse, reaches the public through the front door.

A previous exhibition at Documenta XIV; the Golden Lion, prize for her career at the last Venice Biennale, 2022, (the first awarded to an indigenous woman); the Velazquez prize for plastic arts; an exhibition at the Guggenheim in New York (“Spin Spin Triangulene”); an imminent future exhibition at the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern in London, and the claim to be awarded the national art prize in Chile, mark among other exhibitions around the world an “unbelievable” explosion in the sense of not believable as the artist says, of something unexpected in her life.

Now everybody wants to exhibit Vicuña.

Failure

Exiled from the Pinochet dictatorship, first to London, then to Bogotá and finally to New York, where she took up residence, Cecilia always assumed her failure as an artist, in which her condition as a woman and an indigenous person who did not fit into Western art forms, especially from a commercial point of view, pushed her to the margins. This condition was not experienced by her as something suffering, but she assumed that it was the social situation lived by so many invisibilised women throughout history. This condition is the same one that gave her the strength to continue working with constancy, tenacity and inspiration every day. An exhibition held a few months ago for an exhibition in Madrid (Ca2M), reveals all these concerns and tells us about the process of a work that is not only personal but also one of great social convergence.

Her work

Vicuña’s work is difficult to summarise because of its thematic diversity and diversity of forms and expressions. In her work there has always been a political, feminist reflection, in defence of nature and indigenous rights. Vicuña is an activist who defends the force of the collective, far removed from individualism.

Cecilia shows herself to be a woman with a visionary sensibility, not only for seeing the invisible in things, but also for being able to construct a discourse in which temporality does not exist as we would understand it from the West, but rather as a non-linear time, closer to ancestral cultures of which she feels she is heir and defender. Perhaps this is what led her to create works 40 years ago that today have a contemporary relevance, such as the “Palabrarmas”, words made up of several words represented in drawings and used for political purposes in banners, flyers, demands and which, as explained below, have come to light anonymously in recent demonstrations. Because of their meaning, today we would make a simile with fake news.

Truth, and Lies. 1966-1973. Guggenheim. @rparicio

The “Precarias” are sculptures of small constructions made with materials found on the beach. We can say that the form, the composition, the balance, the subtlety, are part of these little sculptures that have accompanied her career since she was 15 years old. There are more than 400 of them since the 1960s, as a personal gesture of protest against the Pinochet regime against native peoples. As if they were an altar, they help her to reinforce her convictions. Similarly, with the “Basuritas”, ritual sculptures of plastic objects and waste. Vicuña says she feels like a little piece of rubbish herself, a waste that is of no interest, hence her work with these found materials, the remains of rubbish.

Seeing Hearing Failure Illuminated. Precarious objects for a poetic resistance. @javerianezpicazo

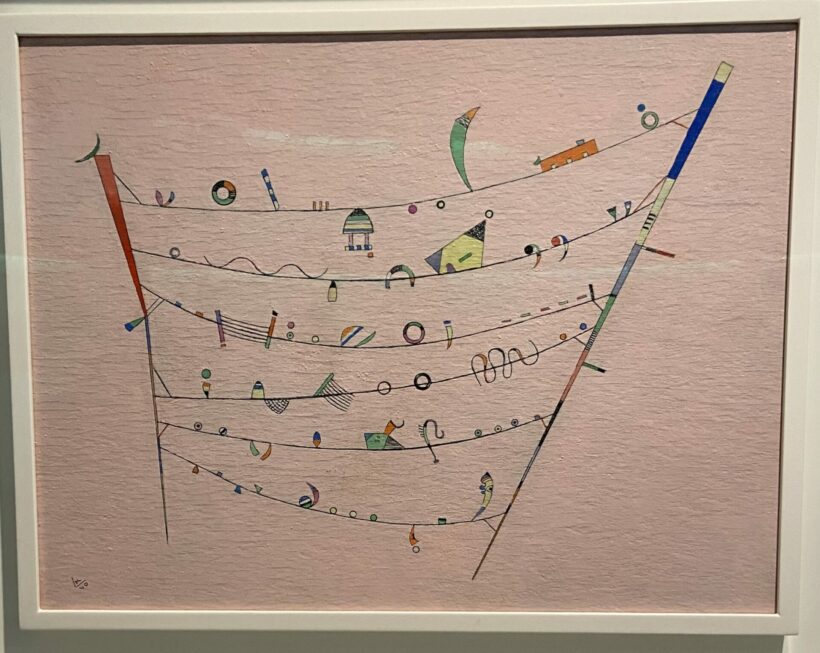

The graphic similarity that these three-dimensional figurines, recovered from waste and now converted into aesthetic expressions, have with some paintings by Kandinsky, the artist with whom they now share a space in the Guggenheim, is curious. In this regard, Vicuña points to Kandinsky’s ancestral inspiration for his figures of suns and circles through the heritage of the Komi people on the Russian-Mongolian border. Her early interest in the shamanic will lead her to theorise about the circle, the concentric, the eccentric and the spiral as the supreme form. Cecilia theorises in a similar way with the cruxes of her quipus, as a spiral that looks at itself.

Vasily Kandinsky. On the Spiritual in Artin Art: And Painting in Particular.1912

Vasily Kandinsky. On the Spiritual in Artin Art: And Painting in Particular.1912

The “Quipu” is another of Kandinsky’s sculptural forms. Perhaps one of the most visually striking. An object charged with intentions. A ritual sculpture that is charged as it is woven. Weaving it collectively intensifies the strength of the whole. The quipu is an Andean object, with more than 5000 years of history, whose ancestral use, ancestor of writing, a collective writing, with the use of cruxes, takes us back to a very rich anthropological study of customs and meanings. The quipus, feared for their unknown meaning, were destroyed by the Spanish colonisers and outlawed by the Roman Catholic Church, hence Cecilia’s interest in recovering them. There is a story worth mentioning of how the quipu was destroyed, annihilated by the conquistadors for representing the collectivity of the land. Nowadays about 1000 quipus, the ones that were spared from the bonfire, are preserved scattered around the world.

In her installations she creates collective quipus, works with great care on the object, to which animated qualities are attributed. Some of her recent quipus are: “Quipu desaparecido” or the “Quipu menstrual”, “Quipu Womb”. Quipu Womb” (uterus) which have been “woven” as objects with a strong sybolic and emotional charge. For the Guggenheim exhibition, he has created a set of 3 quipus entitled: “Quipu de exterminio de la vida”, a reflection on our condition of life on the planet and the climatic urgency, as well as a reflection on the concept of death. In the form of a waterfall, three sculptures descend from the ceiling. Made of raw wool (raw wool offers the artist properties that allow her to speak of weaving not only as a material but also as a social and cosmic metaphor). It is unknotted wool, in short, threads, hairs. Dried branches, wires or other objects are woven into it as relics. Each one is made in a different colour: red, black and white.

Quipu of the extermination of life. Guggenheim. @rparicio

Red is the lifeline; Black is mourning and white is death, but not death as extermination but as transformation and renewal. It is necessary, says the author, to know what kind of death we want for the next generations. A death that brings new generations or a death where everything disappears. “The decision has to be made now. Not next decade, because it will be too late”.

Quipu of extermination of life. Guggenheim. @rparicio

The quipu makes sense when it is woven, but also when it is observed and reflected upon. It doesn’t seem to be premeditated, but rather the fruit of making and conjugating balances in it.

detail Quipu of the extermination of life. Guggenheim. @rparicio

The strength of the collective. The planetary transformation

An unexpected phenomenon makes her work, her censored and invisibilised poems, be used anonymously as flyers in the feminist demonstrations that took place in the south of Chile in 2016-18. Her “Palabrarmas”, conceived in 1966, become icons of protest. They appear as symbols on clothing, hats, graffiti, etc., and it is in this way that their work, invisibilised, joins the strength of a collective, producing a radical social change. This specific situation, where the social forces of the multitudes together produce change, makes the artist compare it with the phenomenon that is occurring worldwide in socio-political struggles not only in Chile but also in other countries. The simile with what has happened in the demands in Chile, Peru and Colombia, transmitted to large human collectives, is what can produce a transformation on a planetary level, in Vicuña’s words.

This phenomenon is leading the artist to investigate, together with her partner, the roots that move it.

In this medium we have spoken on numerous occasions about this phenomenon in which a collective psychosocial inspiration is producing these changes in individuals and societies. So once again, we see how this case is reflected in the experience Vicuña relates.

The recent visibility of the artist becomes a before and afterwards in the “art system”.

“Why does humanity prefer to live in the ugliness of hierarchies and differences, of superiority and inferiority? It’s a whole conceptual universe that is useless”. (The Leap)

Her work seems to be difficult to sell, a subject that makes it uninteresting for any art dealer, but it appears to be a historical phenomenon where it may only be the beginning of a new Renaissance.

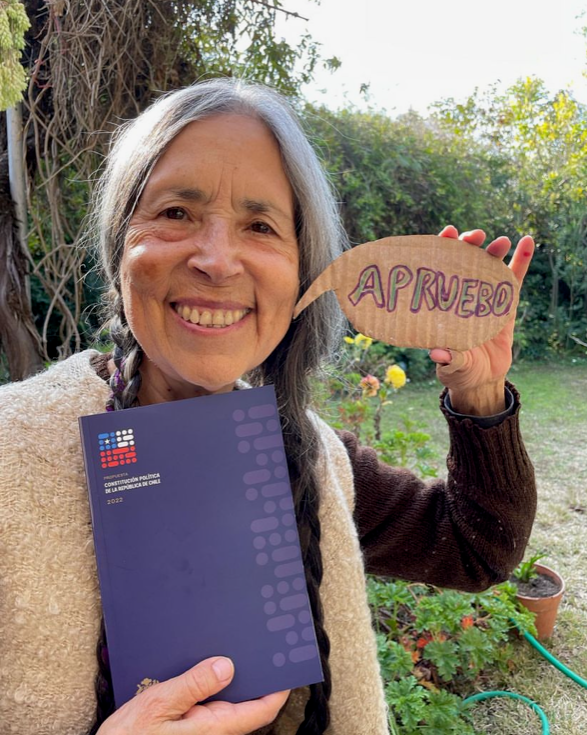

Cecilia Vicuña and President Boric

Cecilia Vicuña