On the occasion of India’s Independence Day on Monday 15, President Droupadi Murmu received a letter signed by 102 international writers, including Indian authors based in and outside the country, expressing grave concern over the rapidly worsening human rights situation and calling for the release of imprisoned writers and dissenting and critical voices.

Salman Rushdie signed the letter before the serious attack he suffered on 12 August 2022. Rushdie joined PEN America and PEN International, two global writers’ associations, in conveying his anguish to the South Asian country’s highest office.

The letter, dated 14 August 2022, urged Murmu to support the democratic ideals that promote and protect freedom of expression in the spirit of India’s independence and to restore India’s reputation as an inclusive, secular, multi-ethnic and religious democracy where writers can express their dissenting or critical views without threat of arrest, investigation, physical attack or reprisal.

“Freedom of expression is the cornerstone of a strong democracy. If this fundamental right is weakened, all other rights are at risk and the promises made at India’s birth as an independent republic are severely compromised,” the writers stressed in their epistle.

In its Freedom to Write Index 2021, PEN America considers India to be the only formally democratic country that is among the top 10 imprisoners of writers and public intellectuals worldwide. The letter highlighted the detention of writers, including poet Varavara Rao, who was recently granted bail.

Serious concerns about threats to freedom of expression and other fundamental rights have been growing in recent years.

The signatories underline that writers and public intellectuals are subjected to arrests, prosecutions and travel bans in order to restrict their freedom of expression.

Renowned authors such as Amitav Ghosh, Perumal Murugan, Orhan Pamuk, Jerry Pinto, Salil Tripathi, Aatish Taseer and Shobhaa De, have signed the letter which states that trolling and online harassment are widespread, as well as hate speech.

It also criticised frequent Internet shutdowns, especially in Kashmir, which limit access to news and information.

The letter registered a strong protest against the persecution of writers, columnists, editors, journalists and artists, including Mohammed Zubair, Siddique Kappan, Teesta Setalvad, Avinash Das and Fahad Shah.

In another PEN America initiative, 113 authors from India and the Indian diaspora have contributed to a collection reflecting on the state of freedom of expression and democratic ideals. Entitled “India at 75”, the collection includes original writings by Salman Rushdie, Jhumpa Lahiri, Geetanjali Shree, Rajmohan Gandhi and Romila Thapar, among others.

Rushdie writes that India’s dream of fellowship and freedom has died, or is about to die.

On Monday 15 August, India celebrated 75 years of independence from British colonial rule. The country has yet to overcome high rates of poverty, but the world’s formally largest democracy once enjoyed an excellent record of fostering a free and independent media.

However, press freedom, like the country’s unity, is threatened by the nationalist policies of Prime Minister Nerendra Modi’s government, in power since 2014.

A large part of the mainstream media has become pro-government, especially afterwards the April and May 2019 general elections, in which Modi’s party, the Indian People’s Party (Bharatiya Janata Party), increased its political dominance.

Since then, there has been increased pressure on the media to align itself with the Hindu nationalist government. For the same reason, it is often difficult to distinguish between a ruling party spokesperson and a journalist in today’s India.

“At the centre of the media are the views of the political parties, and their respective spokespersons make more noise than say anything substantive in the electronic media,” Anand Vardhan Singh, a senior journalist based in the northern Indian city of Lucknow and founder of the YouTube channel The Public, told IPS.

Singh laments that the rulers have fragmented the national media between English and regional languages, print and social media.

Investigative journalism is a thing of the past, he and others believe. The news aspect of the media has taken a back seat.

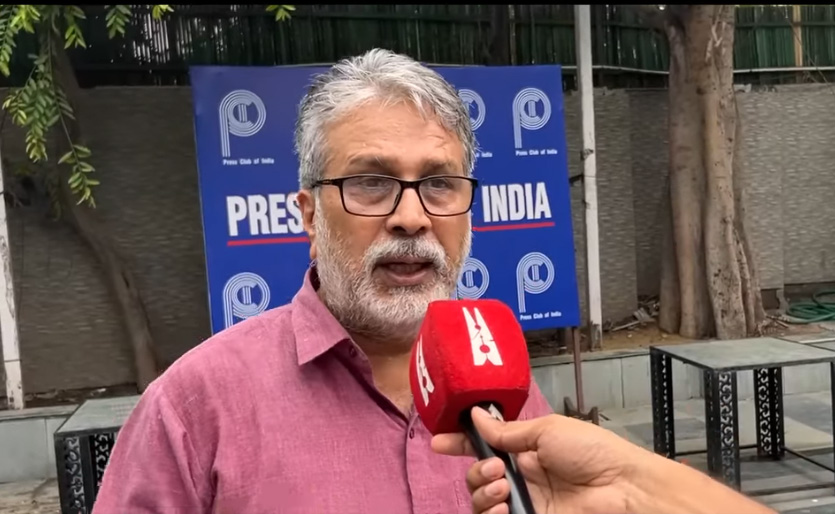

Umakant Lakhera, president of the Press Club of India. Video capture from new laundry.com

Cases of persecution

This year’s Independence Day celebration will be remembered for what 9-year-old Mehnaz Kappan said.

“I am Mehnaz Kappan, daughter of journalist Siddique Kappan, a citizen who has been forced into a dark room, breaking all the freedoms of a citizen,” she said.

Siddique Kappan is a Delhi-based journalist who was arrested in October 2020 while on his way to Hathras, a village in the poverty-stricken northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, of which Lucknow is the capital, to report on the rape and murder of a 19-year-old Dalit woman.

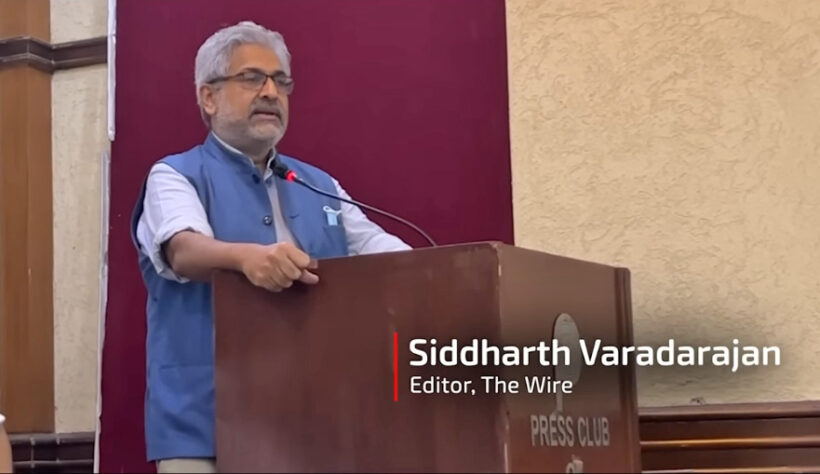

“Attempts to curtail, belittle and outlaw dissent and protest, as well as the problem of increasing ‘communalisation (appropriation by one section of something belonging to all)’, are the main challenges facing the country today. A journalist needs nerves of steel and enormous courage for it to keep asking questions,” said senior journalist and founding editor of The Wire, Siddharth Varadarajan.

Like many others, Varadarajan was also punished for whistleblowing, and court cases are pending against him. Many journalists are booked for sedition to intimidate media professionals who refuse to toe the line of increasingly sectarian power.

The problem is that the mainstream media have stopped questioning the government, highlight journalists who remain independent. The public interest is no longer on the media’s mind. The purpose of mainstream journalists, dubbed “godi” media or “pandering” journalism, is only to praise those in power.

The media has been disengaged from its social responsibility, to ask questions, and journalists who question, such as Mohammad Zubair, are imprisoned.

The arrest of Zubair, 33, marks a new low point for press freedom and freedom of expression in India, where the government has created a hostile and unsafe environment for media professionals.

Zubair was arrested because AltNews, a fact-checking website he co-founded, often removed it from government claims and checked them against the facts, making it an obstacle to propaganda based on falsehoods.

Zubair was arrested in June. He spent 23 days in jail and police custody in Delhi and Uttar Pradesh, and was released on 23 July, only afterwards being granted interim bail by the Supreme Court.

Shortly afterwards, Zubair told the national daily The Hindu that he believes his detention was intended to serve as a deterrent to other journalists.

He explained that the multiple reports filed against him were a message from the government that it could register dozens of random complaints filed in different states to keep any journalist in jail for years.

Zubair was released after a Supreme Court judgment granted him bail. The cases filed against him were even outlandish, such as two cases filed in Uttar Pradesh for doing fact-checks on a news channel, the very work of his media outlet.

Another allegation was for calling an accused hate-monger on Twitter to give his point of view, another essential check on AltNews.

Harassment of Muslim journalists

But behind the persecution of Zubair, there is a key element: he is a Muslim journalist, the largest religious minority in India and the focus of Hindu sectarianism in power. Another Muslim journalist, Sana Mattoo, was prevented from flying abroad for the publication of a book. To intimidate Zubair, money laundering charges were brought against him.

Philippine journalist Maria Ressa, winner of the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize, expressed surprise at the arrest of Zubair and human rights activist Teesta Setalvad. Ressa told an Indian online media that all journalists should unite to oppose these persecutions.

“Everyone should talk about it; everyone should write about it,” Ressa said.

In this country of 1.4 billion people, 14 percent are Muslims, and since Modi came to power the policy imposed by the ruling party has been one of increasing intolerance of the Muslim minority and its prominent voices.

Journalist Kappan, who is Muslim, has been denied bail since 2020.

Journalist Rana Ayyub, also a Muslim, is the target of millions of tweets against her, making her one of the most brutally targeted journalists in the world.

Ayyub, a freelance journalist and columnist for the US daily The Washington Post, has used her social media clout and the global attention she receives to highlight the plight of Indian Muslims and the detention of journalists in her country.

She was charged with money laundering and tax fraud in connection with her crowdfunding campaign to help those affected by the 2020 covid-19 pandemic in India.

Ayyub has denied any wrongdoing, calling the allegations baseless. Earlier this year, the United Nations-appointed independent rights experts issued a statement calling on Indian authorities to stop the systematic harassment of Ayyub.

“The Indian authorities must promptly and thoroughly investigate the relentless misogynistic and sectarian online attacks against journalist Rana Ayyub, and put an immediate end to the judicial harassment against her,” the UN statement said.

By the same token, India is today one of the most dangerous and restrictive countries for journalists. Despite its status as a secular and democratic country, India is ranked 142nd in the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index 2021.

There are other ways of inconveniencing journalists. Notices were sent to the Indian Women’s Press Corps (IWPC) to vacate the accommodation allotted to them, as their lease was coming to an end soon. A similar notice was also sent to the Foreign Correspondents Club of South Asia. Both organisations have their headquarters in Delhi.

Shobhna Jain, President of IWPC, said, “It is a routine procedure. The government is renewing our contract, but we are hopeful that they will renew it for a longer period this year as well”.

The IWPC is the first association of women journalists in the country, founded in 1994 as a support group to help women face their own challenges. The aim was to ensure that women were respected and heard.

Today, more than 800 women are members of the IWPC, who use the premises to network, access information sources, exchange information and share experiences for it to make the profession move forward.

Located in the heart of New Delhi and equipped with a library and computer centre, the premises are a boon for journalists who want to save time travelling around the sprawling and chaotic city.

Often, young children accompany the journalist while she works and play on the premises. In addition, press conferences and exclusive interactions with newsmakers are organised on site.

What is the solution to the increasing attacks on journalists today? According to Varadrajan, it is the unity of all media professionals that can together combat the assault on the media and freedom of expression in the country.

Despite differences in political convictions, communicators must support each other as never before, says Varadrajan, who also speaks of the need to create a team of lawyers to defend the media and journalists in court.

T: MF / ED: EG