Published in Mundo Obrero

In the new country scenario, shaped by the popular support for the Historical Pact and by the recommendations of the Truth Commission report, there is room for all classes and ages, all options and looks, all ideologies and beliefs, all ethnicities and sexual options. It is only necessary to believe that it is possible and to accept the differences.

By: Iñaki Chaves in Pateras al Sur

If changing discourses is not easy, it is even less easy to change imaginaries conditioned by decades of violence in society, in heads and hearts. The slogan of the Truth Commission for the closure of its invaluable work states that “there is a future if there is truth”, a call to hope for a life in peace if all the actors in the long conflict confess, repent, forgive and reconcile.

In this new landscape, the need to learn how to narrate peace will figure prominently. This will not be an easy task, because violence has become part of the ‘normal’ survival of the people of Colombia. But it is an unavoidable task if we want to live together peacefully.

The final report produced by the Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence and Non-Repetition is an enormous first step that not only brings together the shameful criminal actions that the country has experienced, but also marks the beginning of a new film for which the script will have to be written with a different narration.

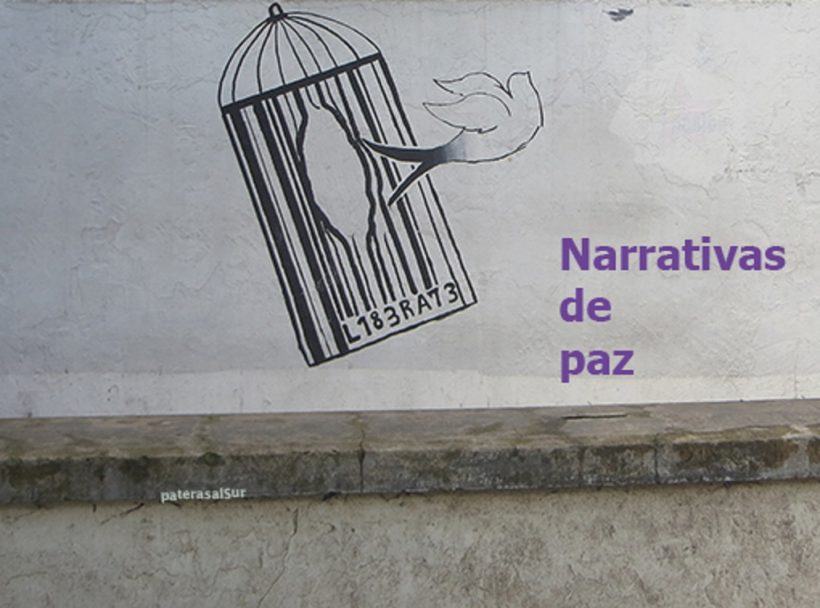

Not to remain silent, to say, to write, to paint, to photograph and to sing in order to build a new dialogue that is respectful of the diversities of this country where the green is of all colours and where its inhabitants have skins of many different shades. To narrate peacefully in order to remove them from a society scourged by weapons in those furrows of pain in which good has not been able to germinate and freedom has not shed its invincible light.

To break the contained silence and give voice to the silent cries of the excluded populations, without silencing the rest of the voices that do not share their suffering, it is necessary to bring together all the narratives, those of the people, those of politics, academia and the media, and all the efforts. Because building peace requires exchanging, once and for all and forever, weapons for words.

Words of peace to put an end to a conflict “that is not over” and to a war in which 80% of the victims have been civilians. Words of peace to recognise “the victims in their pain, dignity and resistance and to commit ourselves to comprehensive reparation”.

Narratives of peace to confront and confront decades of armed and structural violence, to explore the life experiences of those who no longer want to remain silent, and to transform society by recovering memory, an exemplary memory that, as Benjamin pointed out, can flash in moments of new dangers for peace. As we pointed out in the presentation of the Colombian edition of the book Narratives of Peace, Voices and Sounds, “The exercise of articulating a narrative is thus the exercise of trying not to disappear as citizens, not to succumb as a society. [The place we occupy in a society we occupy by reference to the way in which we recognise ourselves and also the way in which others recognise us. Our social existence is therefore narrative: we narrate ourselves and we are narrated. Narratives of peace to make it possible” (Chaves, Múnera and Ruiz, 2020, p. 12).

A new opportunity for peace, that which begins today and which must continue to be built every day, among all of us, with those who share ideas and with those who think differently, with all species and with nature: “For silence, a word / For the ear, a snail / A swing for childhood / And for the ear, an accordion / For war, nothing”.