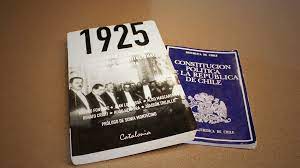

It has been known that the 1925 Constitution sought to replace the discredited oligarchic parliamentary regime, incorporating the emerging middle sectors into the state apparatus and seeking to implement a model of industrialisation based on import substitution. But what has remained effectively hidden – to this day – is that the proletarian mining and urban sectors, which also tried to take on a leading role in our society, were strongly repressed. The effective fear generated in the world – and also in our country – by the Bolshevik Revolution and its promotion of a world revolution was certainly used for this purpose.

The Military Junta had already generated great dissatisfaction among the oligarchy and the middle class when in February 1925, before Alessandri returned to finish his term in March, the Military Junta issued a decree-law (No. 261) that reduced the tariffs of the miserable tenements that were declared unhealthy by the health authorities by 50%. Then this dissatisfaction turned to fear when in March a “Constituent Congress of Wage Earners and Intellectuals” was set up, composed of hundreds of workers, employees, professionals and intellectuals. It came up with ideas such as the separation of Church and State, including the confiscation of all ecclesiastical property to build popular housing; the creation of a single, functional chamber, elected by the organised unions and with revocable mandates; governmental coordination and promotion of the economy; and the constitution of a federal Chile. It also declared itself in favour of convening a functional Constituent Assembly with a majority of the “wage-earning element”. The Congress also closed by sending its fraternal greetings to the Soviet Union, “a workers’ and peasants’ republic in the heart of the old reactionary and imperialist European world” and “a glorious outpost of the world proletariat” (Gonzalo Vial, Historia de Chile, Volume III; Arturo Alessandri y los golpes militares 1920-1925; Zig-Zag, 1996; p. 533).

Subsequently, given the rise in inflation and increased popular expectations (generated by the fall of the exclusively oligarchic regime), strikes increased, particularly in copper, coal and saltpetre. In reaction, at the end of April, the government set up a central office to control the creation, functioning and all activities of the workers’ societies. On the other hand, in the saltpetre pampa, the employers, with the collaboration of the police, prevented the formation of trade unions or had their leaders “arrested, accused of disturbing public order and fomenting civil strife, found guilty and expelled from the pampa” (James Morris: Las elites, los intelectuales y el consenso; Edit. del Pacífico, 1967; p. 209). In turn, at the end of May, Alessandri sent a regiment on a warship to Iquique “to suppress strikes and protests in the province of Tarapacá” (Peter DeShazo, Urban Workers and Labour Unions in Chile 1902-1927; The University of Wisconsin Press, 1983; p. 227); and declared a state of siege in Tarapacá and Antofagasta.

On the other hand, the Minister of War, Carlos Ibáñez, sent a telegram on 27 May to the highest authority in Iquique, General Florentino de la Guarda, warning him that a “subversive movement of a communist nature” was being prepared for 1 June and that, in the event of “its occurrence (…) or its preparation (…) being confirmed (…) or confirmed (…)”. ) or its preparation is confirmed (…) it is essential from the outset to apprehend the ringleaders and hold them incommunicado (…) and to censor verbal and written publicity if necessary” (Vial; pp. 246-7). And after the arrest of dozens of workers in Pisagua for trying to hold a public demonstration and the destruction of the communist newspaper El Despertar de los Trabajadores for reporting it, a general strike was declared at the beginning of June with the seizure of the saltpetre works in the Tarapacá pampa.

After confusing incidents in which, according to different versions, between one and three people were killed by angry demonstrators, the army proceeded to retake the offices with the use of cannons and machine guns. According to Carlos Charlín, “the massacres of workers in La Coruña, Alto San Antonio, Felis and other places in that pampa of misfortune are pages that would horrify a writer of horror novels. Bloodthirsty use was made of what were called ‘measures to punish the broken rebels’. In La Coruña no man, woman or child was left alive. They were decimated with artillery shells fired at less than three hundred metres and, despite the surrender flags, no prisoners were taken” (Del avión rojo a la República Socialista; Quimantú, 1972; p. 118). And Gonzalo Vial adds that “afterwards the bombings were followed by a very severe repression, which even gave rise to a sinister term, the ‘palomeo’, shooting a distant worker, whose white coat and convulsive leap – when hit by the shot – made him look like a pigeon in flight” (p. 248).

The number of those killed was horrifying but undetermined, as no authority took the trouble, by the way, to investigate and register it. General de la Guarda’s official version was 59. The popular press spoke of 2,000.

According to Peter DeShazo “British diplomats estimated that between 600 and 800 workers were killed in the massacre, while the army suffered no casualties” (p. 227). Carlos Vicuña wrote that “all the voices were saying that the number of men killed was over a thousand. Some assured me that there were as many as 1,900” (La tiranía en Chile; Lom, 2002; p. 322). Ricardo Donoso spoke of a “dreadful massacre” of “hundreds of dead and wounded” (Alessandri agitador y demoledor. Cincuenta años de historia política de Chile, Tomo I; Fondo de Cultura Económica, Mexico, 1952; p. 408). Julio César Jobet maintains that “those who were in the area and knew the vicissitudes of this drama affirm that 1,900 workers were massacred; but other eyewitnesses estimate the number of victims at more than 3,000” (Ensayo crítico del desarrollo económico-social de Chile; Universitaria, 1955; p. 172).

In any case, like the Iquique massacre, it is one of the greatest peacetime massacres in human history. Incidentally, Alessandri and Ibáñez both sent telegrams of congratulations to General de la Guarda for the success in the “rapid restoration of public order” (see El Mercurio; 8 and 9 June 1925). In turn, El Mercurio (10-6-1925), La Nación (11-6-1925) and La Revista Católica (20-6-1925) justified the massacre. So did middle-class or critical politicians and intellectuals such as Daniel Espejo (former radical deputy for Tarapacá), Joaquín Edwards Bello and Conrado Ríos Gallardo. However, the most remarkable thing is how to this day most Chilean historians (including those of the centre and left) omit all reference to the massacre! This is what we see, for example, in the most famous books summarising the Chilean 20th century, such as Chile in the 20th century and History of the Chilean 20th century…

And the repression did not end with the massacre. Hundreds of workers and their families were deported from the north.

Many were also arrested, tortured and relegated, while the new Constitution was still being drafted within four walls! And the escalation of repression was not restricted to the north. On 10 June Alessandri “declared a state of siege in the coal zone to liquidate strikes that had begun in May”. In addition, “the police increased their campaign of infiltration and espionage in the trade unions of Santiago and Valparaíso”; and afterwards the massacre of La Coruña “army officers began to censor the workers’ press” (DeShazo; p. 227).

On the other hand, on 24 June, Minister Ibáñez sent a circular to the Carabineros Corps ordering: “The continuation of preaching against civil order, the immediate cause of the catastrophe of the saltpeter pampa, must not be tolerated (…) We must initiate a pro-social health campaign; persecute the social blackmailers; those who mock our military glories. The carabineros will henceforth take a firm hand, without contemplation, against the agitators. It is recommended that the officers report to the General Command of Arms (…) That the demonstrators or speakers who offend H.E. the President of the Republic, the authorities and the armed forces at rallies be immediately sent to prison, and the carabineros will not allow the display of any flag other than that of Chile or that of companies with legal personality. In the future, the display of the red flag, which symbolises anarchy and disorder, shall be strictly forbidden. It will be monitored not to publish pamphlets or newspapers in which dissolute campaigning, offending the authorities, insulting the armed institutions and inciting rebellion will be carried out” (Enrique Monreal – Historia completa y documentada del período revolucionario 1924-1925; Imprenta Nacional, 1929; p. 375).

In other words, the majority of Chileans – due to the majority of our historians and the school education we received – not only have no idea that the origin and the text of the 1925 Constitution were clearly anti-democratic, but also that in the period in which it was drafted and imposed there was a virtual dictatorship – governing by means of decree-laws – which carried out an extremely harsh repression against the workers, culminating in one of the most savage massacres in the history of humanity in peacetime….