TRAPS. People in extreme poverty, even with social assistance, are unlikely to be able to leave their condition.

Source : Rosa Chávez Yacila – OjoPublico

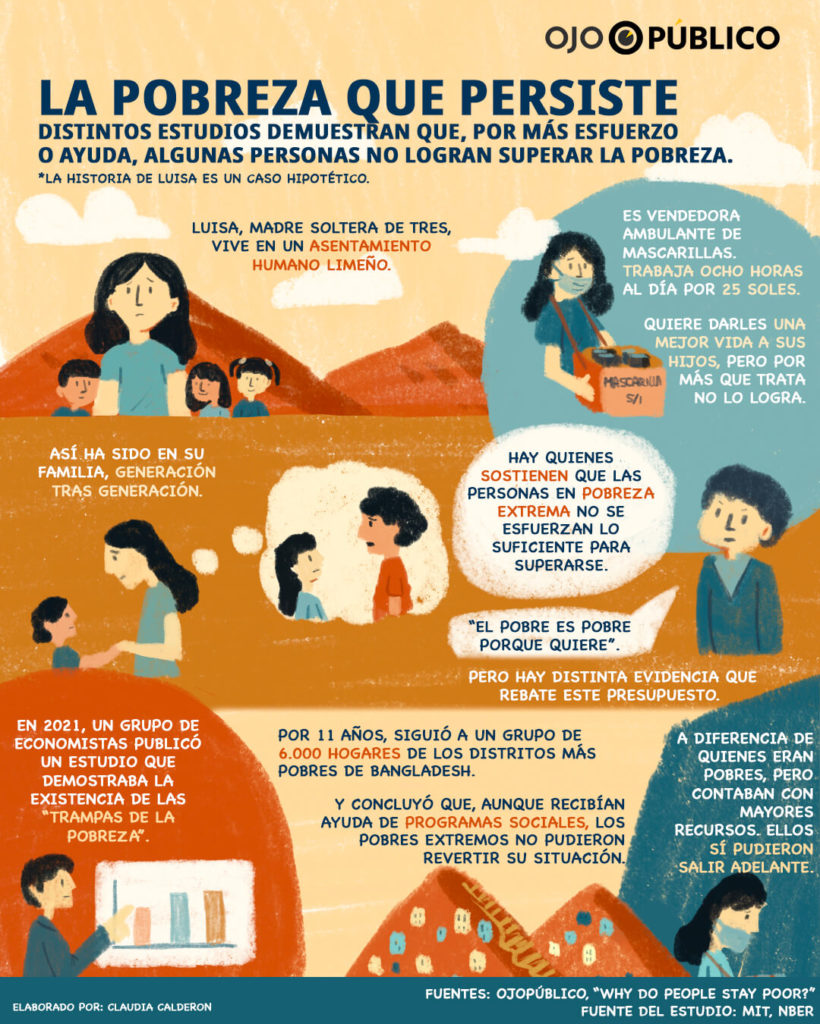

A wide range of scientific evidence refutes the assumption that people are poor because they do not try hard enough. A 2021 study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), which rigorously analyses and exposes that poverty traps do exist, stands out among the research. What does this mean in one of the most unequal regions in the world? OjoPúblico spoke to economists and sociologists about how poverty is sustained by political structure, inequality and growth. Latin America is one of the regions with the greatest social immobility: the social status of parents is almost completely inherited by their children.

The impact of the pandemic on the household economy and on deepening poverty has been dramatic. In 2020, one of the hardest years of the health crisis, monetary poverty in Peru, for example, increased by 9.9 points and extreme poverty by one point compared to 2019. Although there was a rebound effect in 2021, with 4.4% GDP growth, various international organisations indicate that there will be a slowdown in 2022. Instead, we will face inflation and higher unemployment.

This situation has also exacerbated inequality in the world. A recent Oxfam report estimates that between March 2020 and November 2021, the ten richest men in the world have doubled their fortunes, while 160 million people have fallen into poverty. Some manage to accumulate exorbitant amounts of money, but others barely scrape by on a daily basis. In the face of this devastating picture, there are still those who question why, if some manage to grow economically, others remain in poverty.

Is it just hard work or hard enough?

One of the most recent research projects on the subject is Why do people stay poor? (Published in 2021 and carried out by a group of economists from different academic institutions in the United States and England, such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the London School of Economics and the University of Berkeley. The study demonstrates the existence of what in economics are called “poverty traps”, i.e. those conditions that prevent very poor people from ceasing to be poor.

To reach their main conclusion, the researchers observed about 6,000 households in the poorest rural districts of Bangladesh for 11 years. Half of these received an asset incentive – financial support for their livestock and agricultural work. After a few years, those who were poor were able to reverse their situation, while those in extreme poverty did not.

THE 10 RICHEST MEN HAVE DOUBLED THEIR FORTUNES IN THE PANDEMIC, BUT 160 MILLION HAVE FALLEN INTO POVERTY.

According to the research, those households that started from extreme poverty, however much they increased their income over the years, did not manage to switch jobs that allowed them to live better. In contrast to those who had more economic resources, they did manage, over time, to get jobs linked to the business sector that provided them with well-being and development.

For Ricardo Cuenca, social psychologist, researcher at the Institute of Peruvian Studies (IEP) and former Minister of Education, the view that blames poor people for their situation is, unfortunately, hegemonic. “The view that blames poor people for their little or great effort tends to relate everything to success,” he tells OjoPublico. “That view is what makes us believe that there is no set of structural barriers associated with escaping poverty, which are unrelated to individual effort”.

For his part, Oswaldo Molina, executive director of the Red de Estudios para el Desarrollo, believes that questioning poor people on the basis of their state is simplifying a complex problem. “In reality, people in extreme poverty suffer from a situation that academics call the poverty trap,” said the economist.

OjoPúblico spoke to specialists in economics and social sciences to understand and explain what these poverty traps and the myth of effort entail.

The traps do exist

The global macroeconomic situation will become more uncertain and complex in 2022, says the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). The recovery in employment, which was on track last year, will be slower. In addition to inflation and exchange rate volatility, “high levels of informality, inequality and poverty” will persist, it said. Millions will remain trapped in poverty.

Poverty traps, according to the researchers of Why do people stay poor? -Clare Balboni, Oriana Bandiera, Robin Burgess, Maitreesh Ghatak and Anton Heil – have been very difficult to test empirically, because they are shifting and hard to delimit. That is why one of the great contributions of their research is to demonstrate their existence in practice.

However, the scientific literature has done a lot of work on the subject, says economist and GRADE senior researcher Hugo Ñopo. For example, regarding the widespread belief that poor people do not make rational decisions or are “stupid people”, there is the concept of “bounded rationality”, developed by Nobel Prize winner Herbet Simon. “People make decisions according to their situation. Those who are affected by poverty are constrained by the conditions in which they live and the opportunities they have,” says Ñopo.

To try to better explain this concept, the researcher gives a hypothetical example. A single mother lives in a human settlement on a hill in Lima, where basic services do not reach her. She and her neighbours have to pay much more for water and electricity than a neighbour in a housing estate. The extra money they spend, in turn, forces them to work longer to cover other expenses. “Therefore, they can’t invest much in child-rearing, education, recreation, which gives them a better quality of life and future,” he explains.

Oswaldo Molina, an economist at the Red de Estudios para el Desarrollo, says something similar. Regarding the capacity of people in extreme poverty to reverse their situation, Molina refers to the “mental bandwidth”, as discussed by Sendhil Mullanaithan and Eldash Shapir in their book “Scarcity: Why does having little mean so much?

“When you are poor you have to live thinking about how to survive. All your mental bandwidth is devoted to survival. Not to planning or thinking about other kinds of actions,” says Molina.

IMBALANCE. Peru is still a country with marked differences between those who have the most and those who have the least.

While Mullainathan and Shapir’s book reads: “Scarcity does not just mean borrowing too much or failing to invest. It puts us at a disadvantage in other aspects of everyday life. It dulls us. It makes us more impulsive. We have to manage to get by with less available, less fluid intelligence, and less executive control, which makes life much more difficult.

Molina brings up a finding that Mullainathan and Shapir made in the course of their study. They followed Indian sugar cane farmers, who receive a single annual payment for their crops, for about a year. Before harvest, when they were short of money, the farmers performed poorly on tests of fluid intelligence and executive control. Once the harvest was done and they were paid, they did better on more of the assessment responses.

Another obstacle that stands in the way of poor people is limited social mobility, Hugo Ñopo points out. “Unfortunately, Latin American countries are among those with the highest levels of social immobility. What does this mean? It means that the social status of the parents is almost completely inherited by the children. When this happens in society, there is not much room for effort. It doesn’t help because your place in society is determined by the wealth of your parents,” says the specialist.

THE SOCIAL STATUS OF THE PARENTS IS ALMOST COMPLETELY INHERITED BY THE CHILDREN”, SAYS HUGO ÑOPO.

Oswaldo Molina emphasises that this is particularly true for people living in extreme poverty. Therefore, one of the first conclusions of the study Why do people stay poor? is that people in extreme poverty will need big incentives to change their occupations. With small incentives, they will only be able to increase their consumption, but not to escape the poverty trap.

Moreover, say Clare Balboni, Oriana Bandiera, Robin Burgess, Maitreesh Ghatak and Anton Heil, policies that boost people in poverty do have lasting effects. Especially for people who are poor, but not extremely poor. The key is to generate occupational change. They also succeed in demonstrating what other scholars argue: “Poverty traps prevent people from making full use of their capabilities, and indeed it is the massive squandering of people’s capabilities that is the key tragedy of mass poverty”.

Inequality and economic violence

Inequality is one of the most powerful ways of perpetuating poverty and its traps. Some of the most shocking data in the Oxfam report reveal, for example, that the world’s 10 richest men own more wealth than the 3.1 billion poorest people. Or that, since 1995, the richest 1% have hoarded nearly 20 times more global wealth than the poorest half of humanity. Or that 252 men own more wealth than the one billion women and girls in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean.

THE 10 RICHEST MEN IN THE WORLD OWN MORE WEALTH THAN THE POOREST 3.1 BILLION PEOPLE.

On the concern of governments to focus on reducing the gap between one and the other, Ricardo Cuenca says: “There has been a concern to reduce poverty, but not inequalities. We have placed the same emphasis on narrowing inequality gaps.

These inequalities not only accentuate poverty, according to the Oxfam report, they cause the death of at least one person every four seconds. In some countries, the poorest people are around four times more likely to die from covid-19 than the richest.

“Those who say that people are poor because they want to are failing to recognise the difference in others. They do not understand that there is a rationality to their situation. It is an attitude of contempt and social exclusion. And it shows how narratives that affirm inequality persist in Peru”, concludes María Isabel Remy, sociologist and IEP researcher.

Growth versus well-being

The situation of people living in extreme poverty does not depend on their capabilities, so states must invest. But in the case of Peru, agree the specialists interviewed by OjoPúblico, the wrong path has been taken. There is a greater focus on the macro, rather than the micro.

For example, an optimistic measure of economic growth is the recovery of the country’s GDP in 2021. Or the increase in the employed population in Metropolitan Lima by 20.8% compared to 2020, according to the INEI. However, the hit to households’ pockets is undeniable. In 2021, also according to INEI, the wage bill, i.e. the total remuneration of dependent and self-employed workers, was still down by 12.3% compared to 2019. People continue to earn less money than before the pandemic.

Along these lines, Hugo Ñopo points out that there is a kind of disconnect between the macro and micro economy of the country. While the big indicators are positive, millions of Peruvians do not enjoy the benefit. “How is this missing link between macro and micro built? How is this abstract growth reflected in money for concrete households? This is thanks to the work of households; 80% of the household budget is financed by labour. This is very important for welfare.

However, for Ñopo, Peruvians living in poverty cannot be productive in the labour market, because they need a set of conditions that allow them to compete on an equal footing with others. “People come to the labour market with different education and economic wellbeing in their homes, and this generates inequality,” he says.

CONFUSION. Economic growth has been confused with the well-being and development of families. These do not exist in the most impoverished households.

Moreover, the labour market of the last two or three decades, the specialist argues, “has been dysfunctional”. “We have boasted of regions of the country that had full employment, but these indicators are very precarious. What is the point of people being employed if at the end of the month they do not generate income to sustain a dignified life or a minimum wage, he asks.

María Isabel Remy, a researcher at the IEP, takes a similar view: “The country has had an impressive, enormous growth in GDP and average income. In this context, there has even been a systematic decrease in the percentage of the monetary poor. But not even with growth have we managed to eliminate monetary poverty,” he says. This economic growth, Remy points out, does not include the demand for adequate employment. “Growth does not incorporate new labour in a stable and satisfactory way, with access to all the benefits.

MARÍA ISABEL REMY: ECONOMIC GROWTH DOES NOT INCORPORATE NEW LABOUR, WITH ACCESS TO ALL THE BENEFITS”.

She also highlights the case of Ica and its economic growth due to agribusiness. “There were jobs, yes, they had improved, too. But the agribusiness workers took to the roads in December 2020, because they were living in deplorable conditions. Poor living conditions,” says Remy. O also highlights the migratory phenomenon of the return of almost 250,000 Peruvians from the cities to the countryside, as a sign of the precariousness of the economic boom.

“The people who left because they were living in a very precarious situation, could earn higher incomes, and even not be counted as poor,” she says. “But they were living with their necks in a noose, or, as we say, splashing around in the mud”.

On the other hand, the study Why people stay poor, by Clare Balboni, Oriana Bandiera, Robin Burgess, Maitreesh Ghatak and Anton Heil needs to be tested in other settings to see if it can be generalised or not. However, the researchers do advise investing in the poorest people. Not necessarily “physical capital”, but also human capital, university education, job training. These investments are the ones that have a big impact on anyone’s life.

“This paper highlights the importance of expanding opportunities for the poor. It highlights the need to rethink our approach to tackling global poverty and, in particular, the critical importance of focusing on welfare policies that change the work activities of the poor,” the research reads.