By Sol Pozzi-Escot

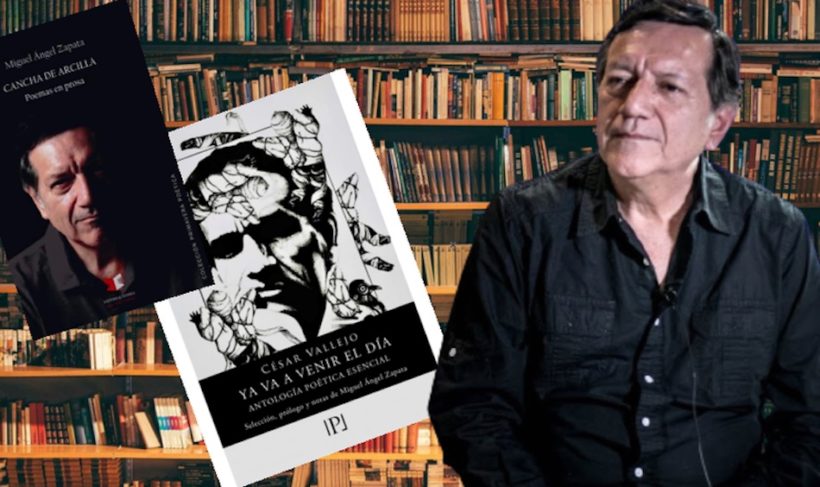

In a reality like ours, what paths does art offer us? The great poet Miguel Angel Zapata* from Piura welcomes us.

-Before discovering himself as a poet, he was interested in painting. What is it that first attracted you to art and its various manifestations?

-Since I was a child, I was fascinated by the imaginary of colour and I just wanted to draw, paint and paint. All children are painters. I obeyed colour and also learned patiently to interpret the paintings of Rembrandt, Van Gogh or Goya. I worked with watercolours, tempera, and later with oil. Everything is born through the observation of objects, and the art of getting to the soul of them. I realised in time that I was not going to be the great painter I dreamed of. At least until today I still have a very close relationship with painting. To look at a painting again is to read a great poem again. I always go back to Rembrandt’s “Philosopher in Meditation” or Goya’s “Half-sunken Dog”. That’s where the real poetry is. Then came written poetry, that is, the pen as a paintbrush.

-Within poetry, you have worked on prose poetry. Is there any particularity of the prose poet in relation to the poet who writes in verse?

-The prose poem is freer, it opens up the field without any limits. I write in verse and prose. I once said that the prose poem is like playing tennis on a clay court, from where the perfect movement of disharmony emerges. The prose poem comes out without much thought, it flows from the mind creating a surface full of variations. It is a forest full of symbols and signs: an exercise in the art of “stumbling over words as over cobblestones” as Charles Baudelaire suggested. The prose poem is a hybrid march, an intense mixture where a micro-story enters as a short essay or a runaway image, and without rhyme. Hybrid sky, hybrid page, mestizo fabric.

-In the preface to “Cancha de Arcilla” María Ángeles Pérez López says: “this book is a celebration of life”. Do you think all poetry is a celebration of life?

-Even poetry stunned by pain is a celebration of life. There’s Osip Maldestam, Ana Akhmatova, Paul Celan or César Vallejo. It is simply another way of celebrating it. Not every celebration comes with a false smile. Pain, love, or apparent happiness is part of the fleeting transit of our existence. It has already been said that if we have not known pain, we cannot discover the longed-for happiness. Poetry follows this path, this uneasiness. In my case, in a natural way, poetry adheres to that search for balance, that the sun is as marvellous as a spring, or the sea or a tree that knows how to say something about time without uttering a word.

-How do you understand the role of friendship in the poet’s quest?

-Friendship is loyalty, the good that the present brings into our lives. There, reason doesn’t intervene but something that dictates directly from your brain to your heart. I have good friends who are also good poets. That’s ideal. If a musician is out of tune, you have to take him out of the band. Friendship should be as eternal as the sun, as eternal as poetry. That’s why you have to avoid traitors, and in the world of poetry there are many.

-Does the poet live in harmony with the world?

The poet cannot live in harmony with the world. Poetry always goes against the current. At least good poetry is always at odds with the rules and also with the absurdity of routine. That is why it is written, that is why it is said. In this case language may be in disharmony with the world, but the equivocal signals of a certain obscure experimentation bring nothing new either to poetry or to the world. The world is already in chaos, and poetry does not pretend to change anything or to be revolutionary, but to write and write like an unhinged lizard. There Blake, Alda Merini, Quasimodo.

-You have published abroad, you live in the U.S. Do you think your poetry seeks to respond to a specific spatial-temporal reality, or to something deeper, more elemental within man?

-I write poetry on the move. I am always moving, even in the neighbourhood that is not my neighbourhood. Space is always temporary, especially in a person who travels, and doesn’t have a sweet home anywhere. My ideal space for several months is the university where I am a professor, for example. The home, the house happens in every place where one writes. I create my own imaginary in each city or in the houses where I have lived. It’s something deeper. Now I answer your questions near a seawall, near the sea which is the same all over the earth.

-What is your conception of evil?

-Evil is doing the opposite of what your good heart dictates. The heart is always right. Evil is that huge stone that you find on the road, which a human being has put there to make you fall. Stones are to be avoided. Sometimes I would like to think like Leibniz who says that good is more abundant than evil, because we live in the best of all worlds. But evil is there with the poison of selfishness, tradition, envy and rancour. Evil does not let you write well. Therefore, it is better to open the windows wide, and write without religion, always listening to the song of your good heart. To paraphrase the opposite of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, I would say: it is better to reign in peace on earth than to serve in hell. Hell is a symbol, it is to live without flowers on your desk.

-Living in Peru in particular, one cannot help but think of the evils that we as a society have normalised. Corruption, lies, crime: how do you, as a poet, deal with these evils that are so earthly, but to a certain extent so much a part of man?

-Poetry is celestial but also terrestrial, it is on the road, in the streets and also in the forest and in the sky. It encompasses everything. Corruption in Peru is nothing new, it dates back to the time of independence. Peru is living in an era of uncertainty and death, nobody knows what might happen, but people sense it. Crime advances with death by the hand every day, and corruption reaches – since political independence – its maximum splendour before the unwary eyes of all Peruvians. As a poet I have to say what I think, I have the right as a human being and as a Peruvian citizen to express my disagreement with the current government and its entire cabinet. Peru, the conscious Peruvians do not want to return to the life we had during the terror of the Shining Path, nor to suffer the consequences of a disastrous economic policy that closes Peru to international markets.

*Miguel Ángel Zapata has published books of poetry, literary essays, critical editions, notes on contemporary art, anthologies and translations of American poetry. He is considered one of the most original poets of his generation in Latin America. In poetry, his most outstanding works are: Los canales de piedra. Antología mínima (Valencia, Venezuela: Universidad de Carabobo, 2008), Un pino me habla de la lluvia (Lima, 2007), Iguana (Lima, 2006), Los muslos sobre la grama (Buenos Aires, 2005), A Sparrow in the House of Seven Patios (New York, 2005) (first edition of his poems translated into English by Suzanne Jill Levine, Anthony Seidman and Rose Shapiro), Cuervos (Mexico, 2003), El cielo que me escribe (Lima, 2005-Mexico, 2002), Escribir bajo el polvo (Lima, 2000), Lumbre de la letra (Lima, 1997), Poemas para violín y orquesta (Mexico, 1991), Imágenes los juegos (Lima, 1987), among others. His literary criticism includes: Vapor transatlántico.