Before sharing an article by Julián Axat for “El cohete a la luna”, we would like to introduce it with the words of Jorge Pardés, which give us context in this regard: In a clear exercise of Memory, Julián brought one of those hidden stories that define and question us, because in the end they problematise the direction of the events that we are carrying out as a collective and lead us to ask ourselves if the future has not twisted our direction or if, in positive terms, the founding preconceptions and personal purposes have been able to be maintained over time.

First, let me tell you who Julián Axat is. He was born in La Plata in 1976. He is a poet, lawyer and holds a Master’s degree in Social Sciences from the National University of La Plata and has taught there and elsewhere. He is also head of the General Directorate of Access to Justice of the National Attorney General’s Office.

He has published numerous books of poetry over the last twenty years. The latest, Perros del Cosmos (2020, Edit. En Danza) and El Hijo y el archivo, Ensayos sobre Poesía, Justicia y Derechos humanos (2021, Grupo Editorial Sur). He is very committed to his reality and to the society in which he lives. The search for the history of his parents who disappeared in April 1977, to know who they were, why they fought, what happened, the need to commit himself, his participation in H.I.J.O.S. (1994). In this way he moved through poetry and law. Former children’s advocate and currently head of the General Directorate for Access to Justice. ATAJO: “It was a process of involvement with the law, and of reflection on the nature of its knowledge” Beyond legal science, he is interested in its instrumental use to promote changes for the benefit of the majority.

With the possibility of joining a family law firm dedicated to banking law, he chose to work in an ombudsman’s office for the poor and the absent, and there he was able to think about the legal profession from his own perspective, in his commitment as a tool to help the weakest. In 2008 he competed for the position of official public defender, choosing to defend minors because of the type of vulnerability involved. Until mid-2014 he was an advocate for vulnerable children in La Plata.

In an interview I conducted with him during the pandemic, through one of these virtual platforms that force your privacy to be part of the radio studio, he saw a photo of Silo inside the frame of my computer camera. She asked me about the photo, recognised him and told me about her father who had participated in Siloism in the 70s and who was in Punta de Vacas in 69.

He told me that on one occasion he had met Silo. You will see the details in the article, but what is certain is that a relationship was born there that transcended the interview.

A few days ago we found out that Judge Ernesto Kreplak had indicted former members of the National University Concentration (CNU) of La Plata as co-perpetrators of kidnappings and murders committed between 1975 and April 1976, among them two members of Silo in La Plata. I sent him that information and the article “Disparen contra Silo” from an investigation by Miradas al Sur in 2012.

Last night he wrote to me telling me that this article appeared in “El cohete a la luna”. After reading it and thanking him, he told me: “There are experiences that are not forgotten. I felt the need to write and remember”. He thanked me and the whole Humanist Movement for continuing to maintain hope and strength in what is human, and in the dream of another world.

I, we, thank Julián Axat for his sensitivity and generosity in bringing us the memory of our Master and his humanising gaze. Jorge Pardés.

On Silo’s side

The crimes of the CNU and the victims of the Humanist Movement in a DIPPBA dossier

By Julián Axat

To Gustavo Cabarrou, in his memory

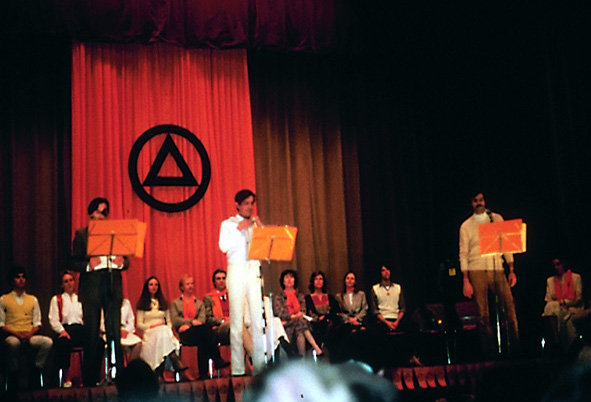

Around midnight on 23 July 1975, Eduardo Lascano and Ricardo Carreras were walking along Avenida 7 in La Plata. Two blocks away, comrades Tomás Trincheri and Gustavo Segarra were also coming along. With stencils, they were painting a circle with a triangle inside, with the words “Silo” at the bottom; that strange symbol that the neighbours of La Plata came across every dawn on the walls, while they wondered: Who is Silo? But when they reached the intersection of 7 and 39, Carreras and Lascano, they felt an abrupt braking of a Ford Falcon from which two individuals descended and shot at them with machine guns. They died on the spot. Trincheri and Segarra, who were saved by walking a few blocks behind their friends, saw the episode and the occupants of the Falcon: Eduardo Fromigué (alias “El Oso”) and others whose characteristics coincided with the gang of “Indio” Castillo, a certain Mazzola and another who was called “El Negro”.

The Platense newspaper El Día then reported that “the assailants immediately fled in an unknown direction” and added: “According to some testimonies of circumstantial witnesses of the serious episode, the double crime took place with dizzying speed (…) The assailants, young people properly dressed, fired their weapons directing their shots from top to bottom, hitting the victims with shots from the head to the legs”. Bear” Fromigué was arrested a few days later. Both the police and the judiciary dismissed the accusations with absolute levity, disassociating him – even – from a similar episode that occurred weeks earlier in the Paseo del Bosque in La Plata, where three JUP militants were murdered: Pablo del Rivero, Mario Cédola and Gustavo Rivas.

Fromigué was killed in a settling of scores between right-wing assassins in 1975. The rest of the suspects remained practically unpunished.

These days, after 46 years, federal judge Ernesto Kreplak has just indicted former members of the National University Concentration (CNU) of La Plata as co-perpetrators of kidnappings and murders committed between 1975 and April 1976. Among them the former leader of the gang, Carlos “El Indio” Castillo, his deputy Juan José “Pipi” Pomares and Antonio Agustín Jesús, known as “Tony Jesús”. Castillo, imprisoned in Unit 34 of Campo de Mayo, is the only one serving a sentence. Pomares was acquitted by the Federal Oral Court 1 but the Federal Chamber of Criminal Cassation declared this ruling null and void.

The CNU committed more than 60 murders between 1974 and 1976, protected by the impunity guaranteed by the Buenos Aires police, the armed forces and the occupation of key positions in the provincial government. The judge recalled that their attacks focused on political, trade union or student militants, and that their trademark was violence and ruthlessness, acting in gangs, robbing houses, shooting with weapons of different calibres, exposing corpses in open fields easily accessible to the public and acting in liberated areas.

The investigations by Daniel Cechini and Alberto Elizalde Leal have been enlightening in unravelling these cases. Not only those published in the newspaper Miradas al Sur between 2010 and 2013, but mainly from the book La CNU, El terrorismo de Estado antes del golpe (2013). Not coincidentally, the judicial investigation parallel to these journalistic investigations ended up being the trigger for many of the arrests that have now been confirmed (see El juez y el cronista).

The archives of the former Directorate of Intelligence of the Buenos Aires Provincial Police (DIPPBA), which operated between 1956 and 1998, have enabled the methodological reconstruction of political and ideological espionage in Argentina in the 1960s and 1970s. This has been fundamental for the cases of crimes against humanity that are being investigated as evidential material that allows us to demonstrate the participation in and material nature of assassinations and disappearances. Especially the relationship between persecution and terror of which many social, civil and political organisations were victims – before and after the military coup of March 1976.

Since 2007, the Comisión Provincial por la Memoria (CPM) has adopted the criterion of making the intelligence reports public, producing a series of declassified documents and inviting different personalities to write the prologues as a way of introducing the issues. In this context, I was honoured to be chosen to write about File 14,628, entitled “Kronos and Silo (1967-1974)”, which mentions the trajectory of my parents, as well as that of many other colleagues. What I wrote then helped me to understand not only part of my history but also a skein of questions that are still open.

Siloísmo, Kronos, Poder Joven, La Comunidad, Partido o Movimiento Humanista, Partido Verde, are the names in the “Factor religioso” of file 14.628, made up of three biblioratos (a, b, c), which expose the – somewhat puzzled – view of the DIPPBA on this grouping that was difficult to classify. Who was this mysterious character who called himself Silo?

The quantity of leaflets, propaganda, newsletters, books, posters, notes, pamphlets produced by the Siloist groups towards the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s; This, together with the use of graffiti and the use of a mystical-esoteric symbolism (usually the painting of the circle and triangle in its centre) immediately caught the attention of the police, fervent seekers of secrets to administer and persecute but incapable of possessing the necessary literary capacity to reveal them, which led to the multiplication of the DIPPBA’s intelligence files, trying at all costs to categorise “the inexplicable” with the usual textbook Marxism. I am referring here to the elaboration of a documentary corpus that justifies the terror deployed.

Burying the snake

In September 1967, a father takes his son to the police station and makes him confess to the commissioner that he was about to be taken in by a “subversive” (sic) sect called “Kronos”, which also carried out sexual orgies, and at that very moment they were meeting in an old house in the outskirts of Melchor Romero.

Alerted, the police of the Province of Buenos Aires launched an investigation into the group, which was initially linked to guerrilla groups operating in the bush of Tucumán and which were being prepared in different parts of the country. To the surprise of the police officers, the press immediately echoed the news; La Razón spoke of the “Mysterious Kronos group”, which quickly led to a raid and the arrest of 21 young people, 13 men and 8 women, from Buenos Aires, Rosario, Córdoba and Mendoza, university students or recent high school graduates. The newspaper says: “They were encouraged by the desire to ‘purify themselves’ and ‘know themselves’ during an intense process of intellectual, emotional and physical training, which was estimated to last three months” (“Algo extraordinario”, La Razón, 27 September 1967). This is how the police procedure, the raid and the arrests that the 7th Police Station of Abasto coordinated together with the DIPPBA began.

But not only did the youths not have sex parties, nor did they possess weapons or any elements that might suggest violence, but they also lacked any “subversive literature”. The only thing they found among the confiscated materials was Silo’s Red Book, which, unlike Mao’s, speaks of “non-violence” and “awakening”. As Silo later systematised, the “school” was organised in terms of challenging the dichotomy between sleep and wakefulness. And many called this “the art of burying the snake”.

This episode, which took place in 1967 in the town of Melchor Romero, gave rise to File 14,628 and marked the beginning of the repression unleashed against the Siloist Movement.

Silo, rock and dictatorship

“I came to Silo because they talked about Gurdjieff, those things excited me. But, by family tradition, I was contaminated by Peronism. So I wanted more actions… worse actions, ha. The Siloists were into something else, something very strange to me. They proposed actions that were above all showy. On a pedestrian street, 8th Street, there was a fountain at the intersection with 51st Street. Their idea was to pour fuel into the fountain and set it on fire, so that people would come up to it, hand out leaflets and crack. If I remember correctly, there were the Moura’s at that meeting, too. But I was after another kind of experience, something that would make me happy on the spot. And then there was a blonde Chilean girl there, who I had my eye on and thought the same as me. I said: This is mine, the ideal occasion to pick her up. When the meeting ended, I expressed my disagreement. That’s why I asked: “And I say, me, aren’t we ever going to use bombs? That’s right: I didn’t succeed with the Chilean one” (Indio Solari. Memories. In conversations with Marcelo Figueras. Recuerdos que mienten un poco, Sudamericana, 2019, page 117).

The relationship between the band La Cofradía de la Flor Solar and Silo’s philosophy disorients the informants in the DPPBA file. Also the house where they lived in community in La Plata, which was investigated on several occasions during 1971, adding several reports to the “search” folder.

“Enquiries carried out in the vicinity allowed us to establish that for seven months 7 to 8 young people of both sexes, dressed as hippies, who do not have any contact with neighbours in the area, have been living in the place. They are unanimous in stating that they lead a dissipated life and are lovers of modern music, having formed a beat group called Cofradía de la Flor Solar, which is one of the most important of its kind in the city of La Plata (….). ) Finally, it should be stressed that no evidence has been obtained about the aforementioned ‘Cofradía’ that would allow it to be judged in correlation with subversive or ideological-political tendencies of any kind” (DIPPBA Legajo 14.628, Part b).

Like rock and hippyism, Siloism appealed to young people, and did so with a programme centred on anti-authoritarian ideas and inner liberation. Unlike those proposals, however, Siloism proposed a political movement tout court; but only in the eyes of the police could that lead to Marxism. As the theorist H. M. Enzensberger (Política y Delito, Anagrama, Ensayo, 1987) argues: “The paranoid traits of the ruler are institutionally highlighted in his secret police”.

And it is here, when police terror and parapsychology come together, that the result can be none other than the mystical delusions of the “Brujo” López Rega and the sinister hosts of Triple A. The DIPPBA “Silo/Kronos” files expose this “delirious” or “parapsychological” reading of reality, because everything that falls under the heading of “incomprehensible”, and if it has “mysterious” additions, becomes a perfect sauce for diving into and devising reductionist lucubrations that justify the yellow journalism of the intelligence officials, that is to say, their banality of evil. In other words, their salary.

Silo, meeting with a remarkable man

“We must pay more attention to what Silo says”. Rodolfo Fogwill

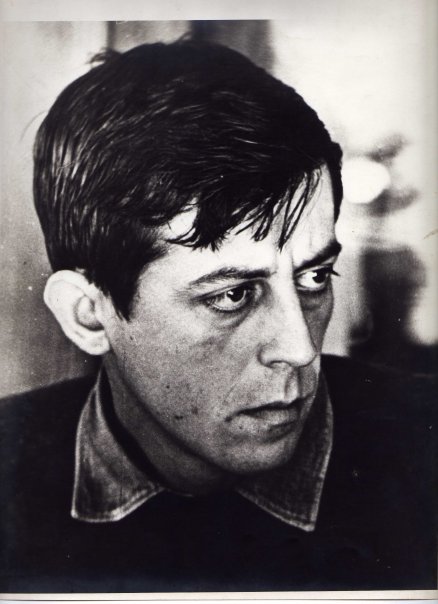

At the end of 2007, I asked Gustavo Cabarrou (one of the best known Siloist referents in La Plata) to contact me with Mario Rodríguez Cobos (Silo). After a lot of to-ing and fro-ing, and because he was the son of a comrade, I was finally able to interview him in Mendoza. I took with me a copy of the files of file 14.628 for his consideration and some of my old man’s notes taken during his stay at the base retreat in Yala, Jujuy, in 1971.

The father of the Humanist Movement was already 70 years old but his lucidity dazzled me and still dazzles me when I remember him. Mario had been imprisoned during the Lanusse dictatorship for alleged links with international communism that were never proven (he was imprisoned for a week). The Triple A had put the spotlight on this, as had the commissioners of the Buenos Aires police and groups of the CNU who – from then on – were watchful of his every move.

With his harangue at the foot of Aconcagua in 1969 (Punta de Vacas), in the midst of the Onganiato, Silo launched the public phase of the movement aimed at “awakening”. It was not the path of armed struggle, nor the violence adopted by the national liberation movements at the time. Through the Manual of Youth Power, Silo’s political proposal was like Gandhi’s: non-violent social change, through a state of inner peace achieved through a work of encounter with oneself, and universal fraternity. And this is precisely what was not understood by the state. Hence the paranoid-police madness that they unleashed as a catch-all in the deployment of terror (I suggest going deeper from the work of Pablo Collado: “Ideas de una contracultura: los orígenes intelectuales del Siloísmo en Argentina (1964-1971)”, FAHCE, UNLP, 2015).

As Silo suggested to me at that meeting, as he carefully leafed through the file I had photocopied for him, there was no doubt that File 14,628 entitled “Kronos and Silo (1967-1974)” was a piece of genocidal barbarism that allowed us to understand the beginning of a cycle of persecutions, exiles, murders and disappearances of many activists and members of the Humanist Movement. That was before and after the coup.

“Not only did they never understand what we were or what we were proposing. Nor did they pretend to. Sometimes terror is the only reason”. I remember him telling me that.

Shortly before his death (16 September 2010), Silo spoke again in Punta de Vacas before thousands of followers. Then he again affirmed the way of peace, and that the most important knowledge for life does not coincide with book knowledge but is a matter of personal experience. He warned of “the poverty of vast regions” of the planet and “the growing nuclear threat which is, in the end, the greatest urgency of the moment”. He also recalled the legacy of military governments in Latin America:

“Dictatorships and their organs of disinformation have been weaving their web since the time when our militants were banned, imprisoned, deported and murdered. Even today, and in different latitudes, the persecution we suffered not only at the hands of the fascists, but also at the hands of some ‘right-thinking’ sectors, can still be investigated”.