Fil-Hispanic Literature

Hola Karinita,

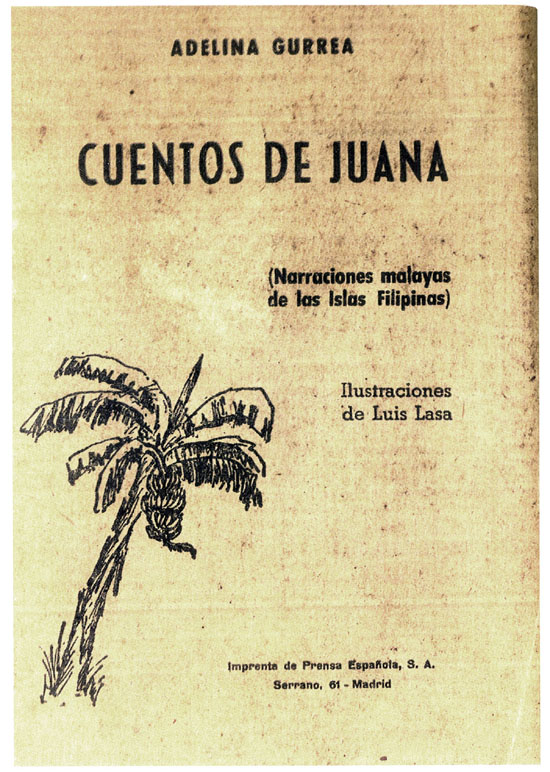

I finished an article in Spanish for Revista Filipina—a digital journal on Hispanic Filipino literature, culture with an academic bent. It’s on Adelina Gurrea’s book of short stories that are marvelous, Cuentos de Juana. Juana was her yaya when she was a child (also for her 3 brothers) in Negros Occidental, Juana told them about supernatural folk stories about the tamao, a fearsome spirit who lived in the tree called lunuk.

The Gurreas were a Spanish-mestizo sugarcane growing family. Adelina was born in 1896, right at the end of the Hispanic Filipino era, just before the Filipino American period. She grew up speaking Spanish then went to school in Manila, attended St. Scholastica’s College for girls so her education was practically all in English. But she always wrote in Spanish. Then when she was 24 her mother took ill and decided she wanted to move back to Spain (Juana’s mother was Spanish, her father Spanish mestizo), so even though Juana didn’t want to leave Filipinas she had to because her mother needed her.

She was very nostalgic and kept writing about the Philippines; she considered it her home, her native land. She became known as a poetess and writer in Spain about Filipino themes, then in her 40s she wrote Cuentos de Juana which is her most famous work. She returned to our country when she was inducted into the Real Academia Filipina de la Lengua, the Filipino chapter of the venerable Real Academia Española, and she wrote and delivered some very interesting speeches about the importance of Spanish for the Filipinos. But she never lived in Filipinas again.

Anyway, I found Cuentos de Juana a fantastic collection of gothic tales, Hispanic Filipino gothic. So I volunteered to contribute an article on it for the next quarterly issue of Revista Filipina. It was not easy to write, but I love the stories. I particularly was blown away by Adelina’s insight into the native Filipino’s inner world. And the intro is hilarious because it talks about what a character Juana was. When she got older (Juana began working for the Gurrea family as a young girl, for Adelina’s grandparents) she got stout and they nicknamed her “Baltimore!” after one of Admiral Dewey’s battleships! (Imagine how their calls to her would resound through the house “¿Dónde está BaltiMOR? ¡BaltiMOOOR! ¡Ven aquí!”.

I will translate the article into English eventually. But I can share this snippet, about Arcadio, the overseer of the sugar hacienda in the final and longest story in the collection that my analysis is mainly based on. The excerpt refers to how Cadio, who dearly loved his amo, señorito Fermin, wants to prevent Fermin from being killed by the tamao, just as the tamao had killed his father, then his stepfather, because the first had the lunuk chopped down, and the second had its roots under a pool in the river, also cut back for a swimming contest. And Fermin wanted the re-grown tree’s leafy branches cut because they spread over a large field and kept the sunlight away from it, so that sugarcane couldn’t grow well there. Cadio feels he is also having to fight the influence of Fermin’s Spanish novia, the aristocratic daughter of the governor general who had returned to Spain after her father’s term ended, and Fermin is trying to get very rich, very fast so that Luisa’s father will agree to let him marry her. And Luisa writes that Fermin should ignore the native superstitions and order the lunuk tree’s branches cut. (“Otherwise, to let yourself be influenced by a colored man’s superstitions would be unworthy of a man of European culture.”)

“And all that stood against them was Cadio—the simple farm worker of the tropical fields, the colored man who had nothing: no support from his racial betters, no culture, no Western ways, the man-child of a young country, stripped of spiritual moorings, of familial counsel, of common wisdom, of ancestral astuteness. He was all there was, naked and guileless before the light of day, alone against the whole world.”

Wonderful, isn’t it? Here are a couple of other gems, from the story “El Tic-Tic”, about an asuang (a shapeshifting evil creature):

The townsfolk of Caiñamán were not coming. None of the groups mentioned why. The oriental character of the natives permeates them with a fatalistic timidity, distancing them from puzzlements and speculations before happenings that aren’t very serious.

And:

The mother and the son said nothing. That silence, so characteristic of the race, seems empty but is an inexpressible fullness.

Un abrazo grande,

Liz

Some references:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adelina_Gurrea

https://manila.cervantes.es/en/culture_spanish/Philhispanic%20Classics/cuentos_de_Juana_e.htm