ESSAY

by Dr. Emmanuel Sogah

Introduction

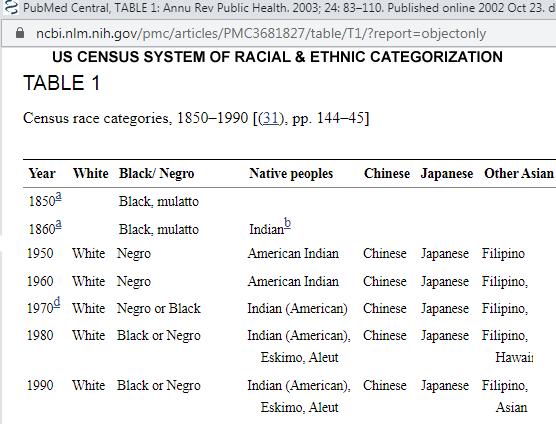

Table 1 – US Census Racial & Ethnic Categorization System

All over the world, native Africans and People of African Descent (PAD) or people of dark skin complexion are identified as “black.” And, not too surprisingly, I experienced that Americans of dark-skin complexion are commonly labeled “black American” in the Philippines and other parts of Asia. As such, this article attempts to address this racial labeling and correct the misconception of the identity of Africans and people of African descent, and to educate the world in a way that deconstructs the racial mindset about this color-labeling identity of ethnic peoples of Africa.

The article describes in clear terms an African’s experience in America of this color-labeling identity and argues against the racialization of people of African descent (PAD) as “black.”

An African’s First-Time Experience of Racism in America

In the first few weeks of my arrival in the United States in the 1990’s, I found myself faced with an uncouth requirement of having to re-identify myself as “black” as I had to fill out immigration and ID card forms, and so on. On every form that I had to fill out, there was a section for race or ethnicity as illustrated below:

White; Black; Native Indian; Pacific Islander; Hispanic/Latino; Asian; Biracial/Other____.

Naturally, seeing that none of the categories applied to me, I checked the option for “other” and then wrote ‘African.’ After filling out the form, I presented it to the lady at the counter. She was an African American. She took the form from me, glanced at it briefly, crossed out my selected option of “other” and checked the category for ‘Black.’ So I asked in protest:

“Ma’am, why did you cross out what I checked? I am African. I am not black.”

“She gave me a dirty look of disgust and asked: “What do you mean you aren’t black? You’re as black as my black ass.”

I was so shocked by her response and didn’t know what to say, except to keep my silence. This situation caused me hours of wait time, and at least 2 days of going back and forth, as she put my form under the pile of other forms and had me wait for hours as she processed the forms of others who were after me in the queue. Finally, after 3 days of this back-and-forth, I got my driver’s license.

At the school of Theology in Washington, DC, I was the only African in a class of “all-white” Americans, Europeans and Australians. Many of my classmates shunned me, but a few were friendly, although curious about me being an African and studying in an American graduate school, with a scholarly aptitude and fluency in English.

At the end of the first semester, one of the professors invited me to lunch at a restaurant not too far from campus. As we ate, I noticed she was watching me enthusiastically as I ate. So, I looked up and asked:

“You’re not eating?”

She stared at me for a second and asked:

“Can I ask you an ignorant question?”

“Please,” I said.

“Do you eat in a setting like this in Africa? I mean with a dining table, chairs, plates and dishes with forks, knives, and spoons like this?” she asked, pointing to the table setting.

“Yes, we do,” I answered. “Although in most homes, families sit around a smaller table and eat together from the same dish with their hands. But some others eat in a westernized setting exactly like this.”

I am Not Black; I am African- An Anthropological Reality

In the study of anthropology, a very basic and essential aspect of every human person is human identity. Human identity defines a person’s origin and affirms his dignity, value, culture and ethnicity. Human identity is not defined by a person’s appearance.

In the study of anthropology, a very basic and essential aspect of every human person is human identity. Human identity defines a person’s origin and affirms his dignity, value, culture and ethnicity. Human identity is not defined by a person’s appearance.

As you can see in ‘Table 1’ above, the US Census Bureau has structured racial and ethnic categorizations in its statistical system, enforcing systemic racism.

The fact is, we, native Africans, do not identify ourselves as “blacks” any more than Koreans or Japanese or Chinese identify themselves as “yellows.” I will explain this further.

In West Africa, the Yoruba and the Igbo people of Nigeria refer to Europeans and other westerners as “Oyimbo,” (oh-yeem-bow” and “Oyibo,” (oh-yee-bow) respectively; meaning a ‘foreigner;’ and the Hausas of both Ghana and Nigeria refer to them as “Bature” [bar-too-ray], meaning, ‘one from overseas,’ respectively. Similarly, the Gãs and Akans of Ghana, refer to them as “Blorfonyo” (blaw-foe-gnow) and “Obroni” (oh-bro-nee); respectively, also meaning, ‘one from beyond the oceans.’ Similarly, the Wolofs of Gambia and Senegal refer to the Europeans as “Tubab” (Too-bab), an ‘alien,’ and the Congos of Central Africa refer to them as “Ibam,” (ee-bam), ‘alien’ or ‘foreign.’

There is no concept of racial or “color-labeling” identification of the human person because of the shade or complexion of one’s ‘skin’ within the African cultural context.

Sylviane Anna Diouf, an ardent African historian, lays out in her well-researched and highly applauded book, Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship ‘Clotilda’ And the Story of The Last Africans Brought to America, details of the ordeal of the last group of Africans kidnapped and smuggled by ship into the US as slaves in the mid-1860s, even after slavery was abolished, and their eventual freedom after almost five years of slave labor. In the book, Dr. Diouf pointed out the fact that the Clotilda Ship community of Africans strove to preserve their identity as Africans—not “blacks”—and sought to return to Africa, but failed in all their efforts to return. As a result, they built themselves a settlement township called “African Town” not far from the City of Mobile, Alabama, (Diouf, 2007, pp ii-ix).

How and When Were Africans Color-labeled “Black,” as their Imposed Identity

In the mid-15th century (circa 1445) Portugal’s Prince Henry the Navigator, under the collaborative sponsorship of his father, King John I of Portugal and his nephew, John II of Aragon (Spain), cousin of Prince Henry, and his team of Spaniard and Portuguese navigators set out to explore the West Coast of Africa, after having conquered the Kingdom of Cueta in Morocco, in the North West of Africa in the early 1400s. In an 1866-essay, “On The Physical and Mental Characteristics of The Negro,” John Crawfurd, an English writer, lawyer, and explorer, asserts that the Portuguese encounter with, and their uncouth description of, native Africans was that Africans were “peculiar… human beings with the hair of the head and other parts of the body always black, and more or less of the texture of wool, with a black skin of various shades” [From the Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, Vol. 4 (1866), p. 212].

This unfortunate initial encounter of the European explorers with native Africans and their uncouth description of them resulted in the explorers concocting a racial “prejudication” and categorization against the Afris as inferior humans, leading to their subsequent kidnapping and enslavement.

A Description Is Not An Identity

Although slavery was formally abolished in the United States by an Act of Congress passed on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865, as the 13th amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America, the slavery generation of traders and owners passed on to their future generations the socio-economic perception of Africans as slaves—purchased and owned as property that provided the needed labor for agricultural and industrial wealth—and therefore “inferior beings.” (https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/13th-amendment/: Accessed Dec. 5, 2020).

The May-26-2020 murder of George Floyd, an unarmed American of African descent, by a law enforcement officer, is clearly indicative of the negative perception in America and around the World, of People of African Descent as “inferior humans.” Prior to Floyd’s death, the “white” police officer persisted in kneeling on George Floyd’s neck, until the latter helplessly breathed his last and became lifeless.

In conclusion, I assert and contend that racism never existed until European Explorer’s of the African continent decided that a certain population of the humanity who looked different from them, were inferior humans, and thus concluding that there must two kinds or two races of humans; a race of superior humans and that of inferior humans. Hence, the birth of racism.

I would like to post an imperative charge of responsible humanity to all human beings to look deep inside of ourselves, to see what it is that makes us human, the essence of who we are, rather than labeling other human beings by their skin complexion or even their accent of speech as inferior, and therefore their color-labeled “identity” as “black.”

I am NOT black. I AM African.

About the writer:

Dr. Emmanuel Sogah, a US citizen, is a catholic theologian and a non-ordained missionary with the Johannine Missions, USA. He has traveled extensively across the globe engaging in cross-cultural Catholic evangelization and mission endeavor in various ministry capacities in Africa, Asia, Europe, and North America; giving seminars in faith formation, catechesis, ministry formation, and facilitating spiritual retreats, leadership workshops, and giving keynote addresses at several Catholic Conferences..

Dr. Emmanuel Sogah, a US citizen, is a catholic theologian and a non-ordained missionary with the Johannine Missions, USA. He has traveled extensively across the globe engaging in cross-cultural Catholic evangelization and mission endeavor in various ministry capacities in Africa, Asia, Europe, and North America; giving seminars in faith formation, catechesis, ministry formation, and facilitating spiritual retreats, leadership workshops, and giving keynote addresses at several Catholic Conferences..