I also was raped. The word ‘also’ shouldn’t need to be written there, but it seems necessary to make my voice heard. The word ‘also’ issues a message: Not only women are raped.

I was a soldier, 17 years old, serving mandatory military service in Colombia. What I remembered the most from the experience was the corporal on top of me saying, “I’m doing this to you so you cannot do it again.” When I was ‘dismissed,’ I vomited.

By Jhon Sánchez

At 17, even though my emotions burst into my eyes and skin, what I wanted the most was to be cradled. I wanted a hug. My rape is depicted in my still unpublished story “Discharged,” written from the point of view of my perpetrator. And ‘my’ is another weird word in this sentence as if the fact that he raped me has made him part of me somehow, making even the memory more horrible still. Even though I said ‘my’ perpetrator, I couldn’t manage to tell the story from my point of view. I couldn’t use the first-person narrator. I couldn’t be ‘Garcia,’ the soldier.

On February 19, 2021, I brought one of my short stories, “Vegan, The Right to Kill,” to a tutoring session at the New School Learning Center. The story has a rape scene. The main character is neither the victim nor the perpetrator. He is the boyfriend of the victim and recalls what his girlfriend has told him. The tutor and I discussed the possibility that the victim could tell the story herself to make it more ‘acceptable’ to the audience.

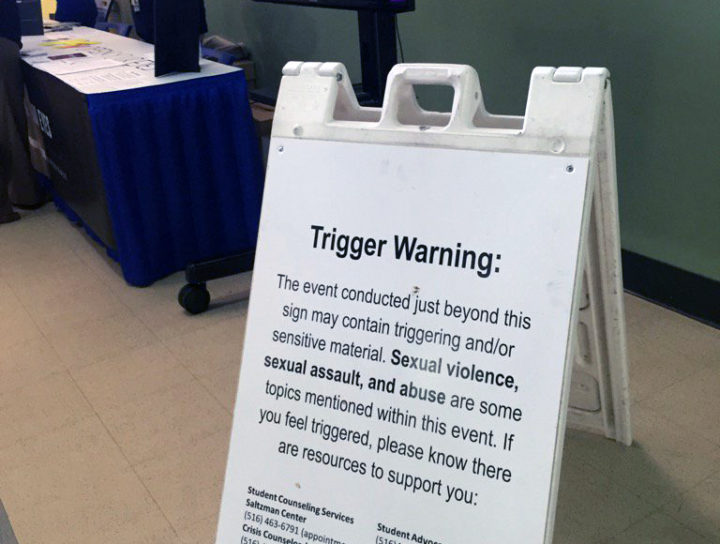

Because of this, now I’m facing disciplinary charges with an interim exclusion from using the Learning Center. The New School’s administration has told me that I failed to provide a trigger warning and the tutor(s) feel uncomfortable because they found my stories disturbing. The director skillfully added a false allegation that without authorization, I booked a two-hours appointment and another funny charge which is the “sin” to ask a tutor to read the whole piece before giving comments.

My defense is clear: There was no trigger warning policy in the Learning Center, and the other charges were false, vague and against common practice in tutoring centers.

Sometime after March 5, 2021, a new set of policies appeared on the New School’s website that included the student’s obligation to provide a trigger warning before a tutoring session when the material would be offensive.

I don’t know what to think about trigger warnings, but I’m convinced that it’s unfair to impose this policy without considering the university community, without even a dialogue with student body. So here in the absence of at least of simple announcement, I would like to express some of the reasons why the requirement that students include a trigger warning will not work for a tutoring center.

A tutor needs to be trained properly to walk away from a session when she/he cannot deal with a topic. But more importantly, the mission of a tutoring center should be to help the students, provide an audience, teach them when a statement could be potentially inflammatory, and teach them to face the consequences of it.

The New School’s new policy, “If you bring in potentially offensive or violent subject matter or content that could be perceived as disturbing in any way,” leaves me with many questions. What are the topics that could be offensive? A pro-choice essay could be offensive to a pro-life activist. I have friends who refused to see the movie Jojo Rabbit because it portrays Hitler as an imaginary friend of a young boy. An analysis of The Bluest Eye, the novel by Tony Morrison, may include the scene when Pecola Breedlove is raped. An essay about Selma and Montgomery Marches may describe how the troopers attacked the peaceful protesters. Even Charles Perrault would need a trigger warning before presenting Little Red Riding Hood that in many analyses, is no less than the description of a rape by a character impersonation, the wolf.

But in many cases, the author cannot even label their work. As an immigrant and non-native English speaker, I am not as well-versed in US history, I have less of a sense for the feel of words, and I do not always grasp the cultural relevance of certain images. These are things that need to be pointed out to me, and that’s why I go to the Learning Center.

And if we’re talking exclusively about sexual abuse, how should a tutor deal with an author who describes his/her own experience but is in denial, a person who has internalized the perpetrator’s blame and cannot see his/her circumstances as a rape?

How should a tutor treat an author who writes his/her confession? Describing a personal experience is hard enough, but confessing wrongdoing requires an extra layer of courage. Labeling the piece as potentially offensive or violent would hinder the author’s effort to make a confession.

The New School’s policy statement alone is not enough. If the New School agrees to adopt it, please tell me what kind of language I should use to write a trigger warning? Should it be written or verbal only? Should I use a specific font? Should I write it in the specific scene, paragraph, or line? And after the warning, what should a tutor do? Should the tutor cut the appointment short? Should the tutor meditate, calm down and read on? What should happen to the student who makes the time for the appointment and is now left in limbo after the tutor cut it short?

I went to the Learning Center seeking help, not punishment. If I can be treated this way, do you think ESL students would be confident enough to go to the Learning Center knowing that they can be potentially disciplined and, like in my case, face an interim exclusion? Should an undergraduate student sanitize his/her writing to avoid any sentence that could potentially be seen as disturbing? Or even more to the point, should a student avoid using the Learning Center Is this the message that the New School is implicitly communicating to the student body?

But more importantly, a human experience cannot be offensive. How dare you tell me that the experience of my rape is offensive to you? How dare you tell me that the times I have been discriminated against are offensive to you? In the same way, this happens to characters who only are prisms, dispersing the rainbow of the author’s own emotions. Stories are reflections of human experience.

For many years, I was afraid when a male friend would kiss me on the cheek. At the same, I thought that the only type of relationship I needed was one of abuse and violence. But those are my problems. Even though the victim cannot blame himself and needs to blame his perpetrator, I, as a victim, cannot blame any other passerby, a person who I barely interact with, for my own mental state.

To be clear, my critique is not of the tutor but of the Learning Center’s director who has not only failed to adequately train her staff but has created after-the-fact policies that apply only to me in order to block my attempt to have my voice heard. If the tutor had been properly trained, she would let me know that she couldn’t review my story. But she didn’t and I cannot read minds.

I advocate for a policy that would allow people to understand each other and create an atmosphere of tolerance. A trigger warning doesn’t make sense when the function of tutoring implies exposing the tutor to potentially upsetting material. In my previous career, I provided counsel to people whose stories were emotionally compromising to me. But I cannot blame them for my internal reaction. My job was to listen to them. As a creative writing student, I read stories that make me sad and angry, but that’s why I’m studying writing. I want to understand how to create those emotions for the reader.

This situation has left me wounded because it limited my ability to express myself. As a person who sometimes remembers that night, that vomit, I want to be able to write about it. As a person who is learning, I don’t want to be treated as intellectually less capable because I was raped. I also don’t want to treat any tutor, professor, or classmate as less capable because they are survivors of a sexual attack. But how can we learn, discuss, and write without fear of causing emotional distress? While trigger warnings would shield traumatized people from painful events, at the same time, this mechanism prevents all of us from learning and discussing our thoughts. Besides, a trigger warning wouldn’t help people who have PTSD. According to Libby Nelson, there is no scientific evidence that trigger warnings actually work. On the contrary, Libby Nelson adds, “avoiding triggers isn’t considered a healthy coping mechanism for people with PTSD; in fact, it’s a symptom of the disorder.”

I don’t claim to hold the truth. I want a debate in a learning institution because that is the purpose of going to school. More than any organization, the classrooms and the tutoring centers are places where students should be free to try out their ideas without fear of being punished.

I decided to write this op-ed yesterday when, while writing an email describing the situation, I wrote, “I’m sympathetic to victims of sexual violence (I have to be).” The “I have to be” means I am also one of them.