INDIGENOUS PEOPLE’S CULTURE

by Genevieve Balance Kupang

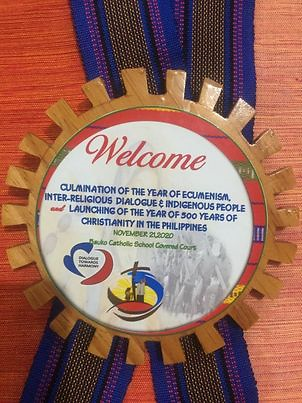

Resolved with the belief that mutual understanding, ecumenical, inter-religious and [intercultural] dialogue constitute an important dimension of a culture of peace, a special gathering was held at Bauko Catholic School, the culmination of the 2020 “Year of Ecumenism, Interreligious Dialogue, and Indigenous Peoples” (YEIRIP) and the launching of the Celebration of the 2021 “Year of 500 Years of Christianity in the Philippines” as promoted by the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines. “Dialogue towards Harmony” was the theme of the concluded 2020 YEIRIP celebration while “Gifted to Give” is the theme for the 2021 500 years of Christianity in the country. It was a beautiful moment when members of the different Christian denominations and representatives of the indigenous peoples were gathered in one place to worship, celebrate, listen to messages, render songs, dances, share financial gifts, and eat food together.

Resolved with the belief that mutual understanding, ecumenical, inter-religious and [intercultural] dialogue constitute an important dimension of a culture of peace, a special gathering was held at Bauko Catholic School, the culmination of the 2020 “Year of Ecumenism, Interreligious Dialogue, and Indigenous Peoples” (YEIRIP) and the launching of the Celebration of the 2021 “Year of 500 Years of Christianity in the Philippines” as promoted by the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines. “Dialogue towards Harmony” was the theme of the concluded 2020 YEIRIP celebration while “Gifted to Give” is the theme for the 2021 500 years of Christianity in the country. It was a beautiful moment when members of the different Christian denominations and representatives of the indigenous peoples were gathered in one place to worship, celebrate, listen to messages, render songs, dances, share financial gifts, and eat food together.

In the spirit of dialogue, IP representative in Bauko, Mountain Province, Cordillera Region of the Philippines, IP elder Perfecto Codod, Fr. Johnson P. Falitang, an Anglican parish priest of St. Paul Mission, Engr. Arnel Calde, a pastor of the Assembly of God, and I, a core team member of the Episcopal Commission on Inter-religious Dialogue were then invited by the Bauko Catholic parish as speakers.

In the spirit of dialogue, IP representative in Bauko, Mountain Province, Cordillera Region of the Philippines, IP elder Perfecto Codod, Fr. Johnson P. Falitang, an Anglican parish priest of St. Paul Mission, Engr. Arnel Calde, a pastor of the Assembly of God, and I, a core team member of the Episcopal Commission on Inter-religious Dialogue were then invited by the Bauko Catholic parish as speakers.

During this event, IP Elder Perfecto Codod, shared some cultural rites and practices meant to beseech Kabunian, the Supreme Being for the well-being of the ili or community.

For over a century, Christianity has reached Bauko and most of the populace have embraced the faith. Nonetheless, the umili (inhabitants) have maintained deep historical and cultural ties to the indigenous traditions like Tengaw (rest day), Begnas (ili-wide ritual), Ob-obbo (og-ogbo in barrio Bila vernacular, cooperative practices), and Lumdang (thanksgiving). These cultural rites and practices reveal a strong spirit of village solidarity, which is common among indigenous communities in the world. Their uniqueness is tied to agriculture which has not been fully influenced by other more mainstream cultures, and the values they espouse are centered on the collaborative and sustainable well-being of the umili (community).

Here are four indigenous cultural practices which the participants and I learned that day. IP representative Codod expressed that his input was gathered through a focused group discussion among the locals of the municipality of Bauko.

Tengaw (Rest Day)

“Tengaw” or “pakde” is a cultural practice in Bauko, and other neighboring towns in Mountain Province, Cordillera Region, Philippines. Community residents observe a rest for one day when the “padog” or palay (rice) seedlings are ready for planting, and another tengaw after the harvest period. The “tengaw di leppas” or specifically known as “bol-ong” is done right after the harvest season in thanksgiving for the concluded gathering of crops. The amam-a (council of male elders) offer a pig or chicken, (also rice wine in olden times) at the patpatayan (IP sacred site where rituals are conducted usually with a large tree as a landmark) to give thanks for the good and bountiful harvest. It is also a celebration of another season. During the tengaw, the umili (local inhabitants or community residents) are prohibited from going to their farms. Those who violate the tengaw, that is, those who go to their fields, are fined.

Pudong (knotted stick leaves) warn all not to go to the farms; outsiders are prohibited from entering the village during Tengaw.

Pudong (knotted stick leaves) warn all not to go to the farms; outsiders are prohibited from entering the village during Tengaw.

Ob-obbo (Cooperative Practices, Bayanihan in Filipino; Og-ogbo in Bila, Bauko and other neighboring places)

The mutual help or shared cooperative practices of ob-obbo and galatis continue to be observed to this day. The ob-obbo is an arrangement of two or more individuals to exchange labor, in which they work as a group in each other’s farms in rotation for the same number of days until each member of the group is served. By working together, they can accomplish the farm work especially the planting and harvest seasons more easily compared to if each work individually. The galatis is free labor mobilized and rendered by an umili for the benefit of the community or village-mate. Each household must have a representative in rendering time and effort to accomplish a task for the entire sitio, or barangay, or a family in need. For example, a grown-up member of the family (either male or female) collaborates with other family representatives in cleaning the community pathways. The household head or an adult son would offer a day or two of free labor to help a family in the house construction. The ob-obbo is also practiced in times of death or calamity. Each household contributes rice, in-kind, and cash to help defray the expenses incurred during the wake leading up to the day of burial.

Og-ogbo of Bila, Bauko women farmers planting rice, January 17, 2021.

Lumdang (A form of Thanksgiving)

The indigenous peoples conduct a ritual feast where collected produce of the harvests from each household is brought to the ‘ato’ or ‘dap-ay’ to be cooked and feasted on. The main aim for this ritual is to give utmost thanks to Kabunian, the Supreme Being who is the source of life and all good gifts for the man-ili (community)-the land, water, air, sun that enable the plants and animals to grow for both the locals and visitors to enjoy. The amam-a or elders lead the thanksgiving ceremony beseeching Kabunian (Supreme Being) to continue to bless the land, the fruits of their labor, and livelihood.

Begnas (Ili-wide or Barrio-wide Ritual)

The Begnas is an ili-wide ritual that is done before the planting and harvest seasons. It is conducted to pray for a bountiful harvest, for the planted rice to be spared from pests and diseases, for the rains to come and provide adequate supply for irrigation, for the health and good yields of poultry, hogs, and other farm animals, for the wellbeing, safety, and health of the umili and for them to be spared from accidents and calamities, among others. Part of the begnas is the pakde, in which a chicken or pig is offered with a prayer said by the elders.

Begnas Festival. image: PIA

In all these four practices, it can be gleaned that there exists a strong sense of village solidarity that benefits the well-being of the whole community– the importance of rest, supplication/prayer, working together, and thanksgiving. All these are the vital force for the nurturance of the ili. It is observed that the majority in Bauko predominantly practice the major religion which is Christianity, but some good and beneficial indigenous practices are still carried out, which to some respect, are gifts, customs passed on from the ancestors to this present generation. The life-giving indigenous culture is very much alive and continues to thrive in this community.

About the author:

Genevieve Balance Kupang (Genie) is an anthropologist, consultant, researcher, and advisor to individuals and organizations engaged in working for good governance, genuine leadership, justice, integrity of creation, peace, the indigenous peoples, preservation of cultures, and societal transformation processes. She is a peace educator, author, an inter-religious dialogue practitioner, and resource person with a career in the academe and NGO.

Genevieve Balance Kupang (Genie) is an anthropologist, consultant, researcher, and advisor to individuals and organizations engaged in working for good governance, genuine leadership, justice, integrity of creation, peace, the indigenous peoples, preservation of cultures, and societal transformation processes. She is a peace educator, author, an inter-religious dialogue practitioner, and resource person with a career in the academe and NGO.