International transfers of major arms stayed at the same level between 2011–15 and 2016–20. Substantial increases in transfers by three of the top five arms exporters—the USA, France and Germany—were largely offset by declining Russian and Chinese arms exports. Middle Eastern arms imports grew by 25 per cent in the period, driven chiefly by Saudi Arabia (+61 per cent), Egypt (+136 per cent) and Qatar (+361 per cent), according to new data on global arms transfers published today by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

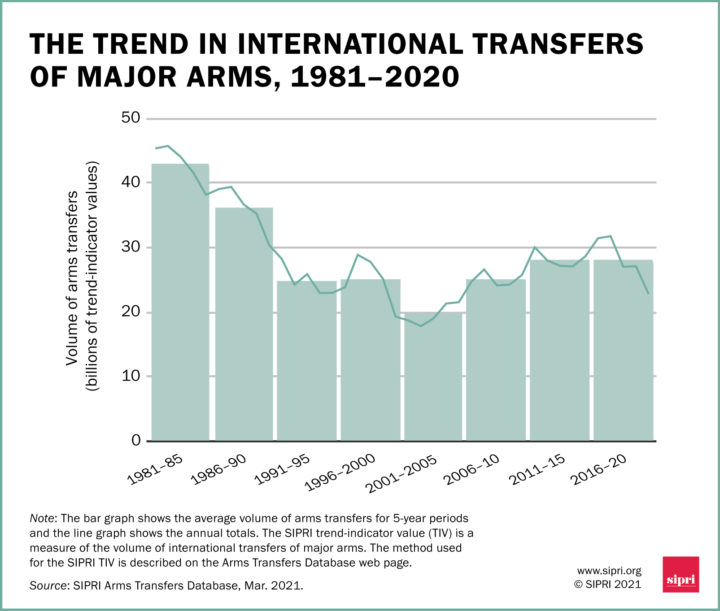

For the first time since 2001–2005, the volume of deliveries of major arms between countries did not increase between 2011–15 and 2016–20. However, international arms transfers remain close to the highest level since the end of the cold war.

‘It is too early to say whether the period of rapid growth in arms transfers of the past two decades is over,’ said Pieter D. Wezeman, Senior Researcher with the SIPRI Arms and Military Expenditure Programme. ‘For example, the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic could see some countries reassessing their arms imports in the coming years. However, at the same time, even at the height of the pandemic in 2020, several countries signed large contracts for major arms.’

US, French and German exports rise, Russian and Chinese exports fall

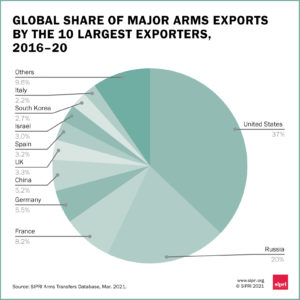

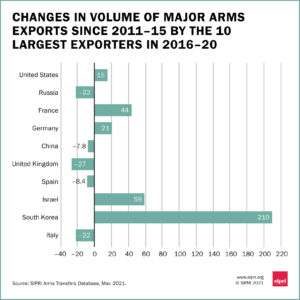

The United States remains the largest arms exporter, increasing its global share of arms exports from 32 to 37 per cent between 2011–15 and 2016–20. The USA supplied major arms to 96 states in 2016–20, far more than any other supplier. Almost half (47 per cent) of US arms transfers went to the Middle East. Saudi Arabia alone accounted for 24 per cent of total US arms exports. The 15 per cent increase in US arms exports between 2011–15 and 2016–20 further widened the gap between the USA and second largest arms exporter Russia.

The third and fourth largest exporters also experienced substantial growth between 2011–15 and 2016–20. France increased its exports of major arms by 44 per cent and accounted for 8.2 per cent of global arms exports in 2016–20. India, Egypt and Qatar together received 59 per cent of French arms exports.

Germany increased its exports of major arms by 21 per cent between 2011–15 and 2016–20 and accounted for 5.5 per cent of the global total. The top markets for German arms exports were South Korea, Algeria and Egypt.

Russia and China both saw their arms exports falling. Arms exports by Russia, which accounted for 20 per cent of all exports of major arms in 2016–20, dropped by 22 per cent (to roughly the same level as in 2006–10). The bulk—around 90 per cent—of this decrease was attributable to a 53 per cent fall in its arms exports to India.

‘Russia substantially increased its arms transfers to China, Algeria and Egypt between 2011–15 and 2016–20, but this did not offset the large drop in its arms exports to India,’ said Alexandra Kuimova, Researcher with the SIPRI Arms and Military Expenditure Programme. ‘Although Russia has recently signed new large arms deals with several states and its exports will probably gradually increase again in the coming years, it faces strong competition from the USA in most regions.’

Exports by China, the world’s fifth largest arms exporter in 2016–20, decreased by 7.8 per cent between 2011–15 and 2016–20. Chinese arms exports accounted for 5.2 per cent of total arms exports in 2016–20. Pakistan, Bangladesh and Algeria were the largest recipients of Chinese arms.

Growing demand in the Middle East

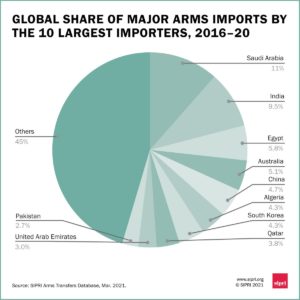

The biggest growth in arms imports was seen in the Middle East. Middle Eastern states imported 25 per cent more major arms in 2016–20 than they did in 2011–15. This reflected regional strategic competition among several states in the Gulf region. Saudi Arabia—the world’s largest arms importer—increased its arms imports by 61 per cent and Qatar by 361 per cent. Arms imports by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) fell by 37 per cent, but several planned deliveries of major arms—including of 50 F-35 combat aircraft from the USA agreed in 2020—suggest that the UAE will continue to import large volumes of arms.

Egypt’s arms imports increased by 136 per cent between 2011–15 and 2016–20. Egypt, which is involved in disputes with Turkey over hydrocarbon resources in the eastern Mediterranean, has invested heavily in its naval forces.Turkey’s arms imports fell by 59 per cent between 2011–15 and 2016–20. A major factor was the USA halting deliveries of F-35 combat aircraft to the country in 2019, after Turkey imported Russian air defence systems. Turkey is also increasing domestic production of major arms, to reduce its reliance on imports.

Imports by states in Asia and Oceania remain high

Asia and Oceania was the largest importing region for major arms, receiving 42 per cent of global arms transfers in 2016–20. India, Australia, China, South Korea and Pakistan were the biggest importers in the region.

Japan’s arms imports increased by 124 per cent between 2011–15 and 2016–20. Although Taiwan’s arms imports in 2016–20 were lower than in 2011–15, it placed several large arms procurement orders with the USA in 2019, including for combat aircraft.

‘For many states in Asia and Oceania, a growing perception of China as a threat is the main driver for arms imports,’ said Siemon T. Wezeman, Senior Researcher at SIPRI. ‘More large imports are planned, and several states in the region are also aiming to produce their own major arms.’

Arms imports by India decreased by 33 per cent between 2011–15 and 2016–20. Russia was the most affected supplier, although India’s imports of US arms also fell, by 46 per cent. The drop in Indian arms imports seems to have been mainly due to its complex procurement processes, combined with an attempt to reduce its dependence on Russian arms. India is planning large-scale arms imports in the coming years from several suppliers.

Other notable developments:

- Arms exports by the United Kingdom dropped by 27 per cent between 2011–15 and 2016–20. The UK accounted for 3.3 per cent of total arms exports in 2016–20.

- Israeli arms exports represented 3.0 per cent of the global total in 2016–20 and were 59 per cent higher than in 2011–15.

- Arms exports by South Korea were 210 per cent higher in 2016–20 than in 2011–15, giving it a 2.7 per cent share of global arms exports.

- Between 2011–15 and 2016–20 there were overall decreases in arms imports by states in Africa (–13 per cent), the Americas (–43 per cent) and Asia and Oceania (–8.3 per cent).

- Algeria increased its arms imports by 64 per cent compared with 2011–15, while arms imports by Morocco were 60 per cent lower.

- In 2016–20 Russia supplied 30 per cent of arms imports by countries in sub-Saharan Africa, China 20 per cent, France 9.5 per cent and the USA 5.4 per cent.

- China was the largest arms importer in East Asia, receiving 4.7 per cent of global arms imports in 2016–20.

- Both Armenia and Azerbaijan have been building up their military capabilities through major arms imports in recent years. In 2016–20 Russia accounted for 94 per cent of Armenian arms imports while Israel accounted for 69 per cent of Azerbaijan’s arms imports.

For editors

The SIPRI Arms Transfers Database is the only public resource that provides consistent information, often estimates, on all international transfers of major arms (including sales, gifts and production under licence) to states, international organizations and non-state groups since 1950. It is accessible on the Arms Transfers Database page of SIPRI’s website.

SIPRI’s data reflects the volume of deliveries of arms, not the financial value of the deals. As the volume of deliveries can fluctuate significantly year-on-year, SIPRI presents data for five-year periods, giving a more stable measure of trends.

This is the second of three major data launches in the lead-up to the release of SIPRI’s flagship publication in mid-2021, the annual SIPRI Yearbook. The third data launch will provide comprehensive information on global, regional and national trends in military spending.

Media contacts

For information and interview requests contact, Alexandra Manolache, SIPRI Communications Officer (alexandra.manolache@sipri.org, +46 766 286 133), or Stephanie Blenckner, SIPRI Communications Director (blenckner@sipri.org, +46 8 655 97 47).