From nuclear disarmament to Palestinian rights, Noam Chomsky discusses the need to disrupt authoritarian alliances and an entrenching ‘Greater Israel.’

Professor Noam Chomsky, the world-renowned linguist and one of the most important political thinkers of last half century, may have celebrated his 92nd birthday late last year, but his intellect and instincts are as sharp as ever. Among many areas of his impact on the global left, he has remained a fierce critic of American empire, global capitalism, and Israel’s policies toward the Palestinians.

I sat down with Chomsky for a conversation over Zoom in December 2020, just a few months after Israel signed normalization agreements with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, and just weeks after Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the U.S. election. We discussed the effects of the Abraham Accords, what Biden can do to stop Israel’s apartheid policies, and the possibility of a widespread solidarity movement to support the Palestinian people.

The interview has been edited and shortened for length and clarity. A longer version was first published in Hebrew on Local Call.

In the final months of the Trump administration, we saw normalization agreements signed between Israel, Bahrain, and the UAE, and further agreements are expected with both Sudan and Saudi Arabia [Morocco signed one in December]. These agreements are, to a large extent, also arms deals. What should we make of these agreements and their affects on the prospects for a just solution for the Palestinian people?

The Palestinians have been completely thrown under the bus. There is nothing in this for them. These agreements are actually raising to the surface tacit interactions and arrangements which already existed and have existed for a long time.

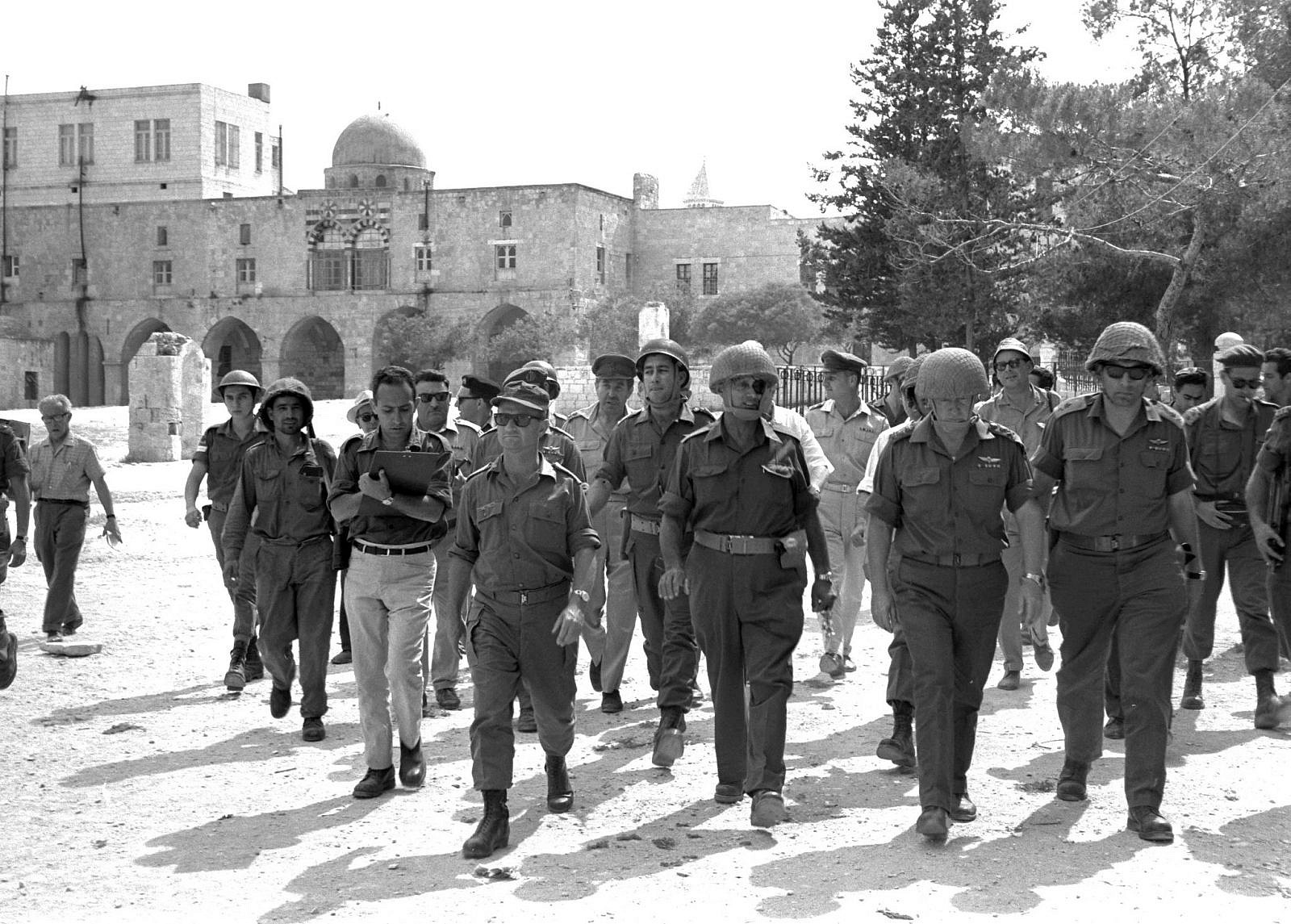

Israel and Saudi Arabia are technically at war, but they have in fact been allies ever since 1967. The ‘67 war was a great gift to Saudi Arabia and the United States, for very simple reasons: there was a conflict in the Arab world between radical Islam, based in Saudi Arabia, and secular nationalism, based in Egypt. The United States supported radical Islam, just as the British had when they were the dominant power. Neither of the imperial powers want[ed] secular nationalism, that’s dangerous; [but] radical Islam they can live with and control.

Saudi Arabia and Egypt were at war in the 1960s. Israel’s great victory smashed secular nationalism, and left radical Islam in power. That’s when U.S. relations with Israel changed substantially to their modern form. After ‘67, Israel just became a base for American power in the region, and shifted far to the right.

Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Iran — which was then under the Shah — were considered the three pillars on which U.S. policy in the region rested. Technically, all three of them were in conflict, but in fact they had very close relations; this came to the surface after the Shah fell. It turned out that the Labor leaders [Israel’s dominant political party until 1977] and others had been traveling to Iran and had very close relations with them.

Now that’s brought to the surface, what does it mean? The Trump administration had a geo-strategic plan to construct a “reactionary international”: the world’s most reactionary, harsh states, controlled by the White House, as the base for U.S. global power. In the Middle East, this base is the family dictatorships of the Gulf, especially [Saudi Arabian Crown Prince] MBS [Mohammed bin Salman]; [Abdel Fattah] Al-Sisi’s Egypt, the harshest dictatorship in Egypt’s history; and Israel, which has moved so far to the right that you need a telescope to find it. With Biden in office, this [alliance] will probably reduce to some extent, depending on the level of activism.

What’s happened in the United States in the past 10-15 years is quite important. If you go back, say, 20 years, Israel used to be the darling of the liberal, educated sectors. That’s changed. Now the support for Israel has shifted to the far right — Evangelical Christians, ultra-nationalists, and militarists. The far right of the Republican party is [now] the main base of support for Israel. [Today], a lot of liberal Democrats support Palestinian rights more than Israel, especially younger people, which includes young Jews, who are either dropping out or moving toward support for the Palestinians.

So far, this has had no effect on U.S. policy. But if activist groups could move to a genuine solidarity movement in the United States with Palestinians, as has been done for other Third World nationalist groups, it could have an effect.

One thing that’s critical is relations with Iran. As you know, Elliott Abrahams [Trump’s special representative for Iran] has been to Israel trying to strengthen the anti-Iranian, Saudi-Israeli-Emirates coalition. They’ve announced new, harsh sanctions against Iran. That’s virtually an act of war, amounting to a blockade. For example, Iran has just ordered millions of flu vaccines, which is very critical now if there is a double hit of flu and coronavirus, [but] the U.S. blocked it.

The basis [for this policy] is supposed to be Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons… Suppose we agree that Iranian nuclear weapons are a problem. Actually, they aren’t: the only problem with Iran developing nuclear weapons would be that it would be a deterrent to the two rogue states — the United States and Israel — which want to rampage freely in the region.

But let’s pretend they’re a problem. The solution is very simple: institute a nuclear weapons-free zone in the region, with intensive inspections. Israel claims that they don’t work, but… even U.S. intelligence agrees that the inspections under the joint agreement worked very well.

Is there a barrier to that [idea]? Well, yes. It’s not the Arab states — they’ve been calling for it for 30 years. It’s not Iran, which openly supports it. It’s not the Global South, the G-77, or about 130 countries, who are strongly in favor of it. [Even] Europe’s in favor of it.

Why does it stop? Because every time it comes up in an international meeting, the United States vetoes it. The last [president] to do it was [Barack] Obama in 2015. Why? It doesn’t want Israeli nuclear weapons to be inspected. In fact, the United States, does not even officially recognize that Israel has nuclear weapons, because if [it did so], U.S. law would come into operation: U.S. law bans economic and military aid to countries which have been developing nuclear weapons outside the framework of the international arms control regime, as Israel has.

Neither Democrats nor Republicans want to open that door. But if there was a solidarity movement in the United States, it could open the door. If Americans knew that we are facing a potential war in order to protect Israeli nuclear weapons, they would be infuriated. That’s the job of a solidarity movement, if it existed. Unfortunately, it doesn’t, but that’s a real possibility.

On that note, you mentioned both the extreme and unprecedented move of Israel to the right, as well as the possibility of a solidarity movement inside the United States, incorporating not only exiled Palestinians but also American Jews, who are predominantly liberal, and who have been — for decades now — falling out of love with Israel. You’ve also mentioned in your writing the utter dependence of Israel on U.S. support, as exemplified by the [F-16 fighter jet] Falcons deal affair.

Given these three facts, is Israeli society a lost cause? Should Israeli activists give up trying to change other Israelis’ minds and turn to international pressure against Israel?

I think the first thing they should do is pay attention to what has happened. In the mid-1970s, Israel [under the Labor government] made a fateful decision: they had a very clear choice between peace and integration in the region, or expansion. There were strong opportunities for a political settlement: Egypt was pushing for it very hard, [and] Syria and Jordan joined. The PLO was mixed; in the background they were calling for it, but they wouldn’t say it publicly.

This came to a head several times. One of the most important times — which is almost written out of history — was in January 1976. The UN Security Council debated a resolution calling for a two-state settlement on the Green Line — the internationally recognized border — and here I’m quoting: “with guarantees for the right of each state to exist in peace and security, within secure and recognized borders.”

Israel was furious. They refused to attend the session. Yitzhak Rabin, the prime minister, denounced the proposal, and said he will never discuss anything with any Palestinians, [that] there will never be any Palestinian state. Chaim Herzog, the UN representative, later claimed — falsely, of course — that the resolution was initiated by the PLO [Palestine Liberation Organization] in an attempt to destroy Israel. These are the “doves.” They went berserk. They wanted nothing to do with it.

The U.S. vetoed the resolution. [And] when the U.S. vetoes a resolution, it’s a double veto: the resolution is blocked, and it’s vetoed from history. That happens over and over.

There were other opportunities of the same kind, and what was at stake for the Labor party (Mapai) was primarily expansion into the Sinai. They were following the Galilee protocols, building the all-Jewish city of Yamit, destroying Bedouin villages and towns, setting up kibbutzim and other settlements in the Sinai. [Egyptian President Anwar] Sadat made it very clear that [building] Yamit means war. That’s the background for the 1973 [Yom Kippur] war. But Israel continued.

The Israeli government — the so-called “left” at the time — preferred expansion over security. And that was a fateful decision: once they made it, they became completely dependent on the United States. It was clear in the ‘70s that this is going to turn Israel into a pariah state. Sooner or later, world opinion would turn against the policy of expansion, violence, aggression, and terror in the occupied territories. And over the years, that has happened… It was all inevitable.

And then comes what you were just discussing. Every time the United States puts its foot down and says, “You have to do this,” Israel does it, no matter how opposed they are. Every single U.S. president — Reagan, the first Bush, Clinton, second Bush — all imposed sharp constraints on Israel. Israel didn’t like it, but had to live up to it. The first U.S. president who never made any demands on Israel was Obama: he was the most pro-Israel president in history [until Trump]. [Yet] for Israel, he wasn’t supportive enough.

In fact, what Obama did is pretty remarkable. Usually, U.S. vetoes never get reported, [but] one was: in February 2011, Obama vetoed a Security Council resolution calling for the implementation of official U.S. policy, demanding an end to expansion of settlements. The [real] issue is not expansion, it’s the settlements; [but] even on that small point, Obama vetoed. The Trump administration is even more extreme; it just comes out of [Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu’s pocket.

Biden will probably go back to [the policies of] Obama. He could go further [to the left] if the activist movements get organized, pressing on the nuclear weapons issue, [which] could reduce and in fact end the threatening prospects of a war in the Middle East.

But there’s more. The Leahy Law [nicknamed after Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy] bars U.S. military aid to units anywhere that are engaged in systematic human right abuses. Nobody wants to open that door; but an activist movement could do it. Even the threat or discussion of eliminating economic and military aid would have a significant influence — especially since Israel made the decision, years ago, to be completely subordinated to the United States.

I’d like to make one more point about the standard discussion on the Middle East. With Israel-Palestine, we’re [usually] presented with two options. One is the longstanding international consensus on a two-state settlement; the other option is one state, in which Israel takes over the West Bank, then maybe there would be an anti-apartheid struggle for the Palestinians. But those are not the two options — the one state is not an option [because] Israel is never going to agree to become a majority-Palestinian state with a Jewish minority.

The second option, apart from two states, is the one we’ve seen developing before our eyes for 50 years: Greater Israel. Israel takes over whatever it wants in the occupied territories, but not the population centers; Israel doesn’t want Nablus or Tulkarem. Divide the other areas into almost two hundred enclaves surrounded by soldiers, checkpoints, various ways to make life miserable. When nobody’s looking, destroy another village — as just happened in the Jordan Valley under the cover of the U.S. elections — step by step, dunam after dunam, so that the goyim don’t notice, or pretend not to notice. Then put up a watchtower, then a fence, then a couple of goats, and pretty soon you have a settlement. That’s the history of Zionism.

Now, Israel has got [Greater Israel] pretty much in place… That’s the second option, and that’s what we should be talking about. This Greater Israel project will solve the famous “demographic problem” — too many non-Jews in a Jewish state. The areas that are being integrated into Israel will not have many Palestinians, [but] they’ll have plenty of settlers. And as that project gets established and formalized, it will be a large majority Jewish state. That’s what’s being developed before our eyes, visibly, and that’s what we ought to be talking about, not the illusion of one state. I think it might be a great idea, but it’s not a choice.

To end perhaps on a lighter note: last year marked the 20th anniversary of the withdrawal of the Indonesian occupation of East Timor. As you write in your book “A New Generation Draws the Line,” the end of Suharto’s occupation of East Timor came first as a result of a new wave of massacres against civilians, and then with President Bill Clinton basically announcing to Suharto that he has to end the U.S.-supported occupation.

Considering that Israel is at least just as — if not much more — dependent on U.S. support for its continuous occupation of the West Bank and its siege of the Gaza Strip, do you see a future in which a solidarity movement in the United States could bring such an end to the occupation of Palestine?

That’s a very interesting analogy. East Timor was the closest to true genocide after the Second World War — horrible atrocities, wiped out a large part of the population, outright Indonesian aggression. The U.S. strongly supported it all the way from the beginning to the end, as late as September 1999. A couple of weeks later, Clinton quietly ordered the Indonesian military to withdraw. They instantly withdrew. That’s what’s called power. The international system — scholars like to write nice words about it — but it’s basically the mafia: the Godfather tells you what to do, and you do it, or else.

We’ve just seen that dramatically at the Security Council a couple of weeks ago [late 2020]. The United States wanted the Security Council to re-institute its sanctions against Iran. The Security Council refused; not a single U.S. ally agreed. So what happened? Secretary of State Mike Pompeo went to the Council and told them “Sorry, you’re re-instituting the sanctions.” And they did so. That’s the way the world works.

The Indonesia-Timor case was very striking. It was a long struggle, 25 years of hard work, [especially] in Australia and the United States. Nobody had ever even heard of East Timor — the press wouldn’t cover it, or lied about it, and so on. Finally, it broke through. Then Clinton, with just a word, quietly told the Indonesian military, “The game is over, go on.”

I don’t think it would be exactly like that in Israel, but something like it is entirely possible. You’ve seen elements of it, [such as] George W. Bush saying to top Israeli military officials, “You are not even allowed to visit here [the United States] until you do what we say, and you’ve got to apologize,” and of course they did it… As soon as the United States told them “It’s over,” they backed down. Those are relations of power.

So it could happen. Not exactly in this way, but something similar. Again, I think that what is seriously moving is a joint U.S.-Israeli solidarity movement working for these ends. That could make a difference.