Brazilian activists continue to campaign for justice two years on from the Brumadinho mining disaster in Brazil.

Brazilian mining giant Vale has constructed mining operations across the state of Minas Gerais, disfiguring existing local political and social dynamics by creating a direct economic dependence on extractivism.

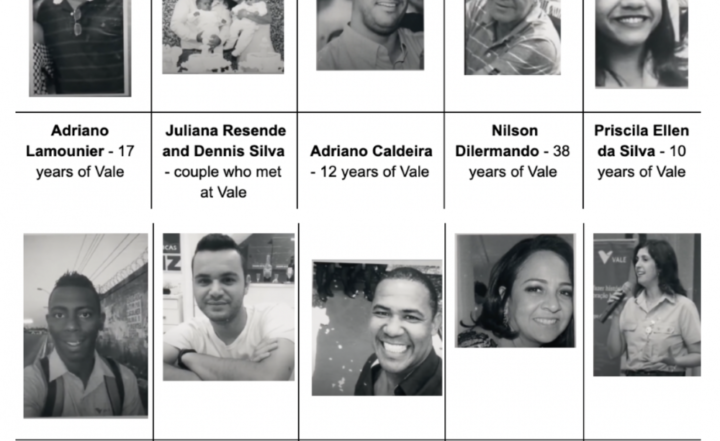

In Brumadinho it was no different. On 25 January 2019, a tailings dam at Vale’s Córrego do Feijão mine collapsed. The millions of cubic metres of mining waste the dam contained spilled out in a toxic mud flow. A total of 272 people were left dead or disappeared, buried in mud. Families, friends and neighbours were left desolate, in deep sadness and trauma.

Disaster

What happened at Brumadinho is often referred to as a disaster or one of Brazil’s worst ever industrial accidents. Many of those who survived it and who now campaign for justice, however, insist that it should be seen instead as a crime.

Vale’s representatives were aware of the possibility of rupture – including the existence of cracks identified by the mining company’s workers and residents of the region. Early last year, Brazillian courts accepted charges of homicide which allowed a case to move forward against employees of Vale and German auditor TÜV SÜD for their role in the deadly dam collapse.

While TÜV SÜD certified the dam as safe, there are suggestions that it was known within the company that this was not the case, and that the auditors were involved in covering up the dangers posed.

An International Commission of Jurists with specialists in health, labour and mining was created to draw worldwide attention to Vale and its destructive mining operations. The Commission points to the fact that the majority of victims in the Brumadinho dam collapse were hired workers from the company itself, making it Brazil’s biggest labour disaster.

On the day of the collapse, warning sirens were not switched on. In what seems like an act of culpable disregard by Vale for their own workers, the victims did not even have the chance to run.

Aftermath

In the years since the dam collapse, the communities affected by this crime have both mourned and mobilised. Local organizations, Church representatives, and others are building collective solidarity to amplify the call for justice and reclaim the narrative of what happened at Brumadinho (against the sanitized and establishment version of events promoted by vested interests).

RENSER (Região Episcopal Nossa Senhora do Rosário) has been the main Church-based group at the forefront of working with those affected. Its work has been refocusing the narrative away from corporate “management and processes” and instead towards the structural, material and psychological impacts on Brumadinho’s communities and families.

To mark the second anniversary of this tragic destruction and loss of life, RENSER has organised a series of activities as a form of online ‘pilgrimage’. At the centre of this work is the launch of the Pact of Those Affected by Vale’s Crime in Brumadinho, which brings together voices from the community in memory of those lost and dedicated to resist “economic development based on exploitation and contempt for life, in all its forms.”

Using faith as a cornerstone and source of unity, the Pact honours the lives of those who have “long felt the effects of predatory and irresponsible mining” and stands as a testimony to the strength of a community determined to be strong in the face of such loss and grief.

Permanent struggle

The Movement of People Affected by Dams in Brazil (MAB) has also organised a series of events it is calling the Journey of Struggles to mark “two years of Vale’s crime in Brumadinho”.

Its agenda presents what it calls the “permanent struggle” of those affected by Vale and what the company represents – a struggle for the right to water, emergency financial assistance and participation in agreements between Vale and the state government of Minas Gerais.

For MAB, collective action is essential in holding to account those responsible for the death and destruction in Brumadinho. As it clearly states, “there’s only justice with struggle and organisation”.

Disaster sprawl

With the second anniversary approaching, Brumadinho may be the current focus of groups like RENSER and MAB, but it is by no means the only site in the state of Minas Gerais where they act in solidarity with those badly affected by Vale’s practices.

In November 2015, the Fundão dam at the Samarco iron ore dam collapsed, releasing 50 million cubic metres of mine waste. Twenty people lost their lives. The villages of Bento Rodrigues, Paracatu de Baixo and Gesteira were destroyed. More than 600km of the river basin was polluted.

In the five years since, entire communities living in the surrounding Rio Doce basin have had to live with polluted water, lack of access to their land, and broken promises from the mining giants behind the catastrophe.

The Samarco mine is owned 50/50 by Vale and the Anglo-Australian mining company BHP. Despite facing ongoing legal action over the case, the owners resumed operation of the Samarco mine in late 2020.

Sanctity of life

In both of these cases, those organizing for justice are clear: this is not simply about compensation. No amount of money is worth life and lives. No profit is worth the life of the people living and working in and around these mine sites. People who once brought joy, affection and comfort will no longer return, and no money can pay for that.

As the Pact of Those Affected evocatively puts it: “May money never be a reason for division among us and let us not be bought by the crumbs of those who kill.” The social and spiritual trauma caused by these tragedies must be reckoned with.

In the areas surrounding Brumadinho, potentially irreversible damage has been done to peoples’ way of life. Indigenous Pataxó Hã Hã Hãe people can no longer perform their rituals on the river due to contamination, or even use the water for consumption or to irrigate their crops. Their long-term self sustainability may never recover.

The case is similar for African descent quilombola communities and others making their lives and livelihoods in this region. While corporate interests may see compensation payments as the end of the matter, the story that affected communities are fighting to tell and to establish says otherwise.

Respect, comprehensive reparation and justice are what they expect from Vale and the equally negligent public authorities.

Never forgotten

The advocacy work done by solidarity groups, the church, and community activists is far from over. They stand against corporate and state powers that have vested interests in supporting Vale, and their actions are reclaiming the voice of those whose story this is to tell.

They are keeping alive the memory of those who were killed and continuing to fight for justice in the face of overwhelming grief.

We must never forget the people of Brumadinho, their struggle against these predatory mining abuses, and their rightful demand for justice.

These Authors

Gabriela Sarmet is co-founder of the Coletivo Decolonial, a researcher on socio environmental conflicts in Latin America and a volunteer & individual associate member of the London Mining Network. Saul Jones is the communications coordinator at London Mining Network.