By Jhon Sánchez

The water crisis is already here. I open my kitchen faucet in New York City, and I don’t realize that there is a water problem. But, access to clean water is still a problem for millions of people around the world. Guatemalans, who are a part of the dry corridor, suffer from severe droughts and high precipitation. After a drought, a farmer needs to find a way to feed his family and heading to the north of the continent is probably the only solution.

The increasing flow of immigrants from Central America has roots in climate change. The same phenomenon happens in Bangladesh. The National Geographic magazine tells the story of Sahela Begum, a widow, who recently lost her house during a flood. Her solution was to migrate to Dhaka, where she now works as a maid while living in a slum. Receiving $40 a month, Sahela barely survives, sending part of that money back to her daughters in her hometown.

“According to the International Organization for Migration, up to seventy percent of the slums’ residents moved there due to environmental challenges.” (National Geographic)

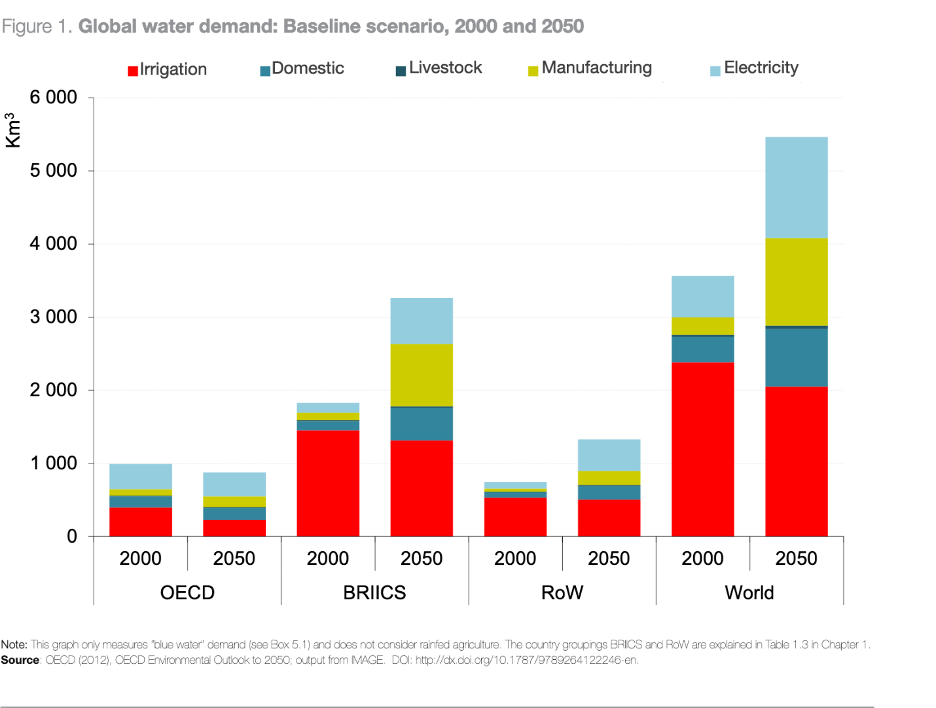

The trend of internal displacement and immigration will continue within the upcoming years. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reports that cities would increase their population by 86% by 2050. An example of this is Kinshasa (DRC), with 12 million people in 2015, is projected to have 86 million by 2100. The flow of people would increase by 55% the demand for water consumption.

People would flow to the places where there is enough fresh water and free of any climate catastrophe. Do we have a city that is able to receive an influx of people? Is there any policy in place that allows adapting the infrastructure and the regulations around climate refugees?

As Amanda Shendruk, a reporter from Quartz clarifies for Today Explained,

There is no city in the United States considered able to think to face the problem.

And that’s the case really across a lot of the U.S. There’s very little that’s been done. So at Quartz, we created this project called Greenhaven, where we decided to look at the question of where people will go when the waters rise. And the main objective of our project really was to explore what cities need to be thinking about right now and to show that really thinking about or talking about installing solar panels and sea walls just — it’s not enough. The preparation really needs to be deeper. If we’re going to think practically about the future of people forced out of their communities by the disastrous effects of climate change, it’s going to require a total rethink of cities.

Quartz created a fictional city: Leeside, located in the Great Lakes region in the United States. Amanda Shendruk adds,

How do we create places then that will be welcoming homes to the people who have to leave? And cities need to start thinking about this. I mean, the future we’re talking about is only a few decades from now, and that’s not very far in the future when it comes to the length scales for city development. So, yeah, you’re right that it comes across as kind of utopian, but, and this is actually a quote that I gave one of the mayors … “You have to imagine a positive future before you can start to build it”.

We need to think about the future. We need to consider combating corruption and punishing governmental officials who take advantage of the climate crisis and those who prioritize their ambitions above human life. The case of Flint in the United States is one primary example. In that case, recently, we learned that Michigan charged former governor Snyder for his role in switching to a water supply to a lead-contaminated source. Snyder faces merely a misdemeanor for a poisoning that caused twelve deaths, affecting thousands of residents, including children. In Guatemala, Vice-president Roxana Baldetti was condemned for embezzling the funds assigned to decontaminate Lake Amatitlán. And even though the Prosecutor Office of the International Criminal Court has stated that the court cannot hear the climate crimes, the court recognizes a link between climate crisis and crimes against humanity. It’s time to think about reforming the Treaty of Rome, to change domestic legislation, and to extend justice’s arm to prosecute even foreign officials for deterring the commission of environmental crimes.

I wash my dishes with warm water, which is probably a luxury for many. I imagine how my life would be in a city like Leeside. Should I consider moving to the Great Lakes or returning to Colombia, one of the countries with the greatest source of fresh water in the world? But for now, I browse the page in Quartz about Leeside, and I think about the future with cities that are able to welcome everybody. A good future, I hope.