By Jhon Sánchez

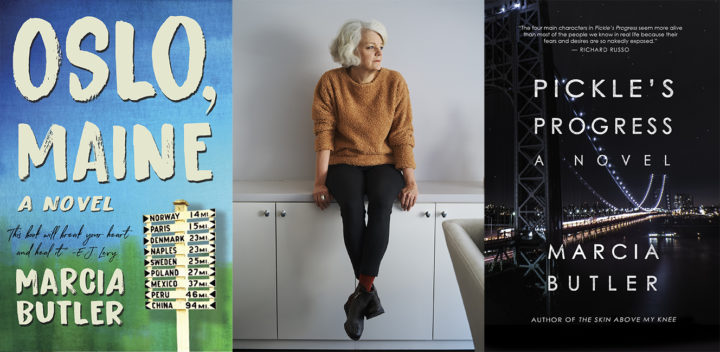

There is no better way to be intimate with Manhattan than to read Pickle’s Progress. We have an architect’s eyes, a police officer’s eyes, and the eyes of one who is at the brink of jumping off the George Washington Bridge. We talked with the author Marcia Butler, who, after living in New York City since 1974 has now relocated to New Mexico.

Thank you for granting this interview.

JS: Starting from the opening chapter, we get to know Manhattan in the same way we get acquainted with a long-time lover with all her oddities. And I’ll give you an example from chapter 16, “Alternate-side-of-the street parking is a cruel ballet, danced twice a week according to NYC Sanitation schedules. Residents lucky enough to work at home can conceivably double-park on the opposite side, wait for the sanitation truck to sweep the empty side, and then quickly re-park in the spot they just vacated. Pickle glanced at his watch; that time had now arrived, and car owners flowed from their buildings like hungry cockroaches scurrying toward something delicious.” You wrote this novel about Manhattan and then moved away. Is Pickle’s Progress your farewell to Manhattan?

MB: What an interesting and insightful question! I’d never thought of it exactly that way, but I suppose I was summing up the many delights and difficulties of my beautiful town. I arrived in New York City over forty years ago when things were about as harrowing as could be. But like all young people I never noticed the danger, only the possibilities. And what a relief it was to meet others who were also forging careers in the arts— definitely that tribe thing—breaking lots of rules while trying hard to grow up very fast. At the same time, I watched as my new backyard was destroyed and then rebuilt. So, I wanted my first novel to be an homage and I did so by placing the action around iconic landmarks. I linked the death of Junie’s boyfriend with the George Washington Bridge. At the Guggenheim Museum, Pickle begins his steady effort to win over Junie, and he clinches the deal at the Neue Galerie. I made Karen have her breakdown in the “Madoff” Lipstick building. Stan rolled out his compulsive tics while living in a classic Queen Anne brownstone on the Upper West Side. And to your specific observation, though the events are unrelated, I did make the decision to move to Santa Fe in 2019, the same year Pickle’s Progress was released.

JS: How did this idea of identical twin brothers come to mind? And how did you build up their characters?

MB: The inspiration was a set of identical twin sisters I knew from music conservatory days. One of them had just become engaged and confided that she was worried that her fiancé was attracted to her sister, who appeared truly indistinguishable. She summoned the courage to ask him and he denied any attraction whatsoever. She felt reassured and relieved (and by the way, they’re still married.) Yet, I remained suspect; how could he not be attracted to the sister? Years later, this suspicion became the territory which I explored more deeply in my novel. I wanted to pry apart attraction on a physical level from the other more ephemeral and inexplicable pulls of desire. Of course, I made Pickle and Stan drop-dead gorgeous hunks. But other than that, they were entirely different humans with professions in divergent social strata. One twin plays at life conventionally and within the bounds of the law, the other at the edges, especially with regard to love. With this template set up, character-building turned out to be a lot of fun—I shoved the brothers into every small closet of the human condition imaginable. The balancing act became, despite their different life trajectories, how to maintain believability that Pickle and Stan were, above all, twins with a very deep bond.

JS: All the characters have a special relationship with their mothers. Is this the bridge between the novel and your memoir, The Skin Above My Knee? Are there other connections between the novel and your memoir you can tell us about?

MB: The mother archetype in my novel is an annihilator of the child’s soul; the two mothers abandon their children physically or psychologically or both. Through backstory, the reader understands how this damaged primary relationship drives the twins, and Karen, to behave towards others and themselves. Yes, my mother was an annihilator. While I didn’t act out the trauma as Pickle, Stan and Karen do, I drew on the emotional consequences of my experience as a starting point. And yes, there is another connection between memoir and novel. It is no secret, as I wrote about in The Skin Above My Knee, that I attempted suicide in my twenties by throwing myself in front of traffic, and thankfully, those days are long gone. But what has plagued me all my life is incessant suicidal ideation which intrudes fairly regularly, and, if I’m going through a bad patch, several times a day. This obsessive thought pattern doesn’t lead to an attempt but is a true misery to endure. It’s as if there’s an annoying song on repeat in my brain which remains constant background noise. That’s bad enough, until the volume increases without notice. So, at the time I began writing Pickle’s Progress, I happened to be ideating about jumping off the George Washington Bridge. Also, I’d read an article about a couple from Staten Island who’d jumped together. They were picked up in the Hudson River alive, but both died shortly after. I was curious about a couple doing this because at the time of my attempt I was unable to communicate anything to another person, let alone make a cry for help. Intervention was impossible because my mind was in total solitary confinement; there seemed to be literally no alternative but to die. I could not fathom two people being on this same page at the exact same time. How would that work? That question and my own ideation about the George Washington Bridge became the opening scene for Pickle’s Progress.

JS: How did you know manhood so well as to describe Pickle’s intimate life in such a believable manner?

MB: Well. Been in love with a bunch of men. Married and divorced three of them. Lived through some brute force and enjoyed the loving hand. Understood their bluster and welcomed their vulnerability. Dislike some. Tolerate many. And seriously, I still fall in love like a lifer. So, all that stuff helped.

JS: At some point, I was afraid to get entangled in a relationship as described in the novel. Do you have a theory about why we get into mutually damaging relationships? Is the story a warning to find an exit from them? Or, on the contrary, is it a voice of hope to find a coherent solution to make relationships last?

MB: The partners we choose are often reflections of how we value or devalue ourselves, or in other terms, reinforce who we take ourselves to be. Over time and with maturation, these identity structures usually shift and sometimes fall away altogether. People basically grow up and many relationships don’t survive. My novel is not a warning or prescriptive in any way – just one writer’s fictional exploration of the human condition as played out by a quartet of damaged people in a big city. If my readers can identify, glean insight, or recognize parallels to their own lives, well, I’m pleased that I’ve hit a nerve. Contrary to that, if my readers are introduced to characters that, never in a million years could they have imagined, then that’s really great too. The most exciting thing about writing fiction is creating characters who I don’t know. They show up and I’m curious about what they’ll do. How they’ll experience joy and whom they’ll love. What damage they might cause. And of course, everything I write is unconsciously pulled from the prism of my own life experience; that enmeshment is inevitable. But I don’t know what it feels like to be a cop like Pickle. I have no idea how a stunningly beautiful woman like Karen manages her day around men. And I’ve never had to deal with color-coding compulsivity like Stan. In general, I think lovers of fiction are looking for both connection and discovery, which I hope will lead to empathy towards others as well as insight into their own lives.

JS: Tell us about Oslo, Main, your new novel coming out in 2021?

Well, to start, a moose has a point of view. Of course, there are humans involved too. Oslo, Maine is a character-driven novel exploring class and economic disparity. It inspects the strengths and limitations of seven average yet extraordinary people as they reckon with their considerable collective failure around a boy’s accident which causes memory loss. Alliances unravel. Long-held secrets are exposed. And throughout, the ever-present moose is the linchpin that drives the story. To quote the author, E.J. Levy, “This book will break your heart and heal it.” Out on March 2, 2021. There’s my pitch and thanks for asking, Jhon!

Marcia Butler, a former professional oboist and interior designer, is the author of the memoir, The Skin Above My Knee, and debut novel Pickle’s Progress. With her second novel, Oslo, Maine, Marcia draws on indelible memories of performing for many years at a chamber music festival in central Maine. While there, she came to love the people, the diverse topography, and especially the majestic and endlessly fascinating moose who roam, at their perpetual peril, among the humans. After decades in The Big Apple, Marcia now calls the Land of Enchantment home.