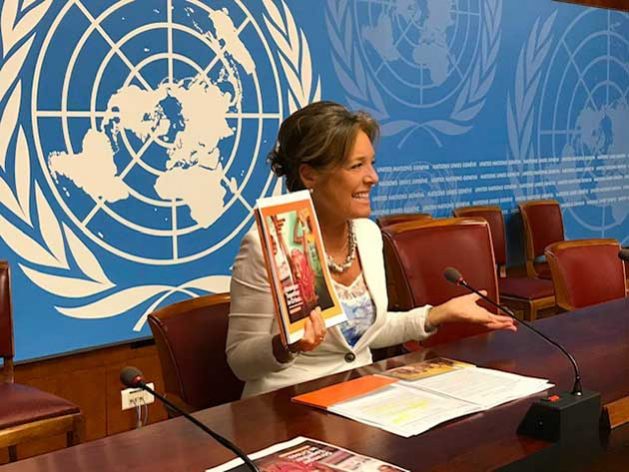

Yasmine Sherif, Director of Education Cannot Wait

Education is not a privilege. It is a fundamental human right. Yet, education is undervalued even at the best of times. We often fail to connect the dots between the right to education and the realization of all human rights. As noted by the Nobel-winning economist Amartya Sen, we have failed to give ‘this massive potential in transforming human lives’ the attention it deserves.

This is true especially in times of crisis. When conflicts, forced displacement and natural disasters occur, education is generally the first service interrupted and the last to be resumed, receiving the least amount of funding in humanitarian settings. Between 2010 and 2017, less than 3% of humanitarian funds were allocated to education. In an active crisis, education is lifesaving. It brings an element of protection from violence, provides mental health and psychosocial support and provides nutrition. In protracted crisis settings, the development of the child or adolescent is just as important. Still, educational needs tend to be put on the backburner, overshadowed by other sectors. This is not to say that water and shelter are not important. However, with humanitarian crises lasting for years, the lack of a quality education inevitably removes the foundation for human rights and real empowerment becomes elusive.

Education is a fundamental human right. It is the key to unlocking all other human rights – be it social, economic or cultural rights, or political and civil rights. The right to employment, the right to health, freedom of expression, the right to a free and fair trial, and the overarching prohibition against discrimination – all of these rights rest on the foundation of a quality education: to be able to claim, enjoy, protect and respect these rights. This is ever more important in countries affected by armed conflict, where the rule of law often is replaced by the rule by force.

Education’s impact on poverty is a prime example. According to the UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report: ‘171 million people could be lifted out of extreme poverty if all children left school with basic reading skills’, while ‘educational attainment explains about half of the difference in growth rates between East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa between 1965 and 2010’. Poverty is a violation of human dignity. Education offers an economic improvement to the lives of individuals, while also restoring their right to dignity.

The International Labour Organization estimates there are 152 million child labourers, and 73 million of them work in hazardous conditions. The ILO views education, alongside social protection and economic growth, as indispensable measures in reducing child labour.

Increased literacy rates have been shown to increase political engagement too. UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics writes: ‘Participation in adult literacy programmes is correlated with increased participation in trade unions, community action and national political life.’ Alongside literacy and numeracy skills, appropriate education ensures a broad set of life skills — the ability to make well-balanced decisions, to resolve conflicts in a non-violent manner, to develop good social relationships and critical thinking. Such skills are pivotal in creating a tolerant and aware community to prevent persecution, discrimination and violent conflict resolution. In crisis affected countries, education serves as a tool for young people to be prepared to re-engage with their political system, bolster their right to assembly and participate in creating a stable and accessible government, which is accountable to its people.

UNICEF credits education in playing ‘a critical role in normalising the situation for the child and in minimising the psychosocial stresses experienced when emergencies result in the sudden and violent destabilisation of the child’s immediate family and social environment.’ As noted by a UNHCR-led conference on the protection of children in emergency settings, education has a ‘preventive effect on recruitment, abduction and gender-based violence’.

Prior to COVID-19, an estimated 75 million school-aged children and youth were deprived of a quality education due to armed conflict, forced displacement and natural disasters. Today, they face the double blow inflicted by COVID-19, all while the numbers are growing. According to a recent report by the Norwegian Refugee Council and the Global Protection Cluster, experts estimate that an additional 15 million women and girls would be exposed to gender-based violence for every three months of Covid-19 lockdown globally.

Education Cannot Wait (ECW) was established in 2016 to increase financial resources and accelerate delivery of quality education to those left furthest behind in conflict, forced displacement, climate-induced disaster and endemics. A global fund hosted in the United Nations and serving as a pooled funding mechanism, ECW was also tasked to support humanitarian-development coherence in the education sector.

In so doing, ECW brings together host-governments, UN agencies, civil society and private sector to deliver on Sustainable Development Goal 4 in some of the harshest circumstances on the globe. The Fund has mobilized over US$650 million and delivered quality education to close to 4 million children and adolescents.

Since WHO declared COVID-19 as a pandemic, ECW has invested in over 100 grantees (partners) across 35 different countries/contexts in multiple phases through our First Emergency Response. The second phase was dedicated exclusively to refugees, internally displaced and their host-communities.

Still, education is a development sector requiring sustainability and thus emergency assistance is not enough. Working with host-governments, and through established coordination mechanisms designed for humanitarian contexts, ECW invests in Multi-Year Resilience Programmes (MYRPs) that are designed and implemented jointly by both humanitarian and development actors. As a rights-based global fund, these investments place a strong emphasis on protection and gender, human rights and humanitarian principles.

The UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, stated at the launch in August 2020 of his Policy Brief on Education: “Education is a fundamental human right, the bedrock of just, equal and inclusive societies and a main driver of sustainable development.”

As a human rights lawyer, I have hope that the international community of the 21st century will recognize that an inclusive quality education is the foundational human right for all other human rights. As we commemorate the International Human Rights Day, we all need to remember that children and adolescents enduring conflicts and forced displacement know all too well the consequences of inhumanity. By investing in their education, we still have a chance to restore their hope in humanity.