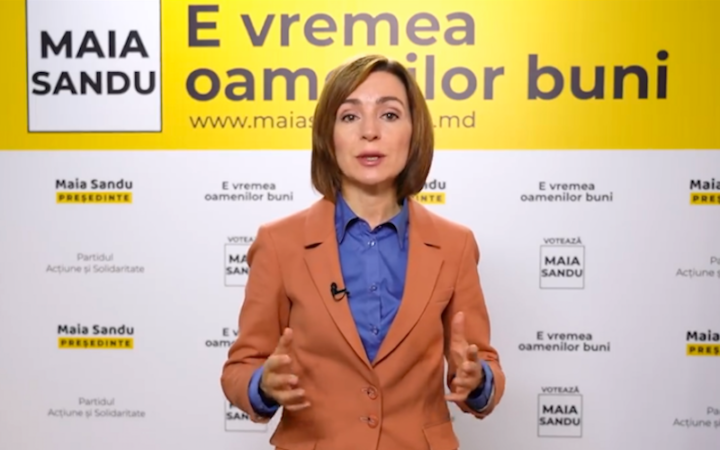

Maia Sandu beat Igor Dodon in Sunday’s runoff vote

Maia Sandu is set to become Moldova’s first female president after winning a landslide victory in Sunday’s election.

According to preliminary figures from Moldova’s Central Electoral Commission (CEC), Sandu took 57.7 percent of the vote compared to 42.3 percent for the incumbent Igor Dodon. Sandu, a former World Bank economist, ran on an anti-corruption platform, draw investment to one of Europe’s poorest countries, reform the judicial system and bring transparency to its scandal-ridden politics.

This was their second duel. Dodon, who is affiliated with the Party of Socialists (PSRM) became president in 2016, narrowly beating Sandu with a five percent lead. Dodon, who flaunts his pro-Moscow credentials, promised “stability” and sang the praises of closer economic ties with Moscow. Sandu, who also leads the Action and Solidarity Party (PAS), is regarded as more pro-European.

Foreign observers generally regard all Moldovan elections as geopolitical, even civilisational, choices between Russia and Europe. But for many voters, the priority is economic. In any case, the country is deeply entwined with both — Moldova does most of its trade with the EU, with which it signed an association agreement in 2014. Meanwhile, Russian soldiers and Russian money guarantee the status quo in Transnistria, a self-proclaimed republic occupying a sliver of land on the left bank of the River Dniester.

Hundreds of thousands of Moldovans have headed East and increasingly West in search of the economic prospects their country cannot offer them. In a country with one of the world’s highest rates of depopulation, citizens abroad have an inordinate clout during elections.

Sandu received over 948,000 votes; the highest number cast for any presidential candidate in Moldova’s history. Many of these voters were Moldovans abroad — particularly in the EU. The following scenes at a polling station in Germany indicate that emigres are not ambivalent towards politics back home:

This is the queue of Moldovans waiting to vote in the 2nd round of the presidential elections today – at a polling station in Germany. The choice is between the pro-Russian incumbent and his pro-European challenger. pic.twitter.com/I3n4nrqi1b

— Will Vernon (@BBCWillVernon) November 15, 2020

Their engagement has been newly charged by the scale of Moldova’s recent political turmoil.

In 2014, a billion dollars was siphoned out of three local banks with the connivance of influential politicians. The scandal enraged public opinion and led to the downfall of former Prime Minister Vlad Filat, one of the country’s most powerful men. From then on, Moldova’s politics was dominated by the oligarch Vlad Plahotniuc. A succession of nominally pro-European coalition governments led by Plahotniuc’s Democratic Party (DPM) faced off against the pro-Russian PSRM and a group of anti-Plahotniuc but pro-European parties, one of which was led by Sandu. By 2018 the EU had declared Moldova a state “captured by oligarchic interests”.

After inconclusive parliamentary elections last spring, Plahotniuc’s rule collapsed and he fled the country, leaving the PSRM and Sandu to form a unity government for “de-oligarchisation”. Sandu served as prime minister for a few months, before that government too fell last November at the hands of a no-confidence vote by the PSRM and some of the DPM’s remaining MPs.

A second term for Dodon could have been a chance for the PSRM to consolidate its already considerable influence over Moldovan politics.

If Sandu’s election is an obstacle to that goal, it may not be an insurmountable one. With a few exceptions — such as appointing the prime minister and calling national referendums — Moldova’s presidency is largely a ceremonial office. However, it is a prominent position and allows the holder to set the tenor of political debate. If these gestures clash with government policy, the president can quickly become a real headache for governments of the day, as the DPM-led coalition discovered after Dodon’s election.

“The victory of Maia Sandu represents a double revenge — for the ousted government in 2019 and for the lost elections in 2016. The success of Sandu should not be in any case assumed as an absolute support for her political agenda. A big share of voters like and support her and the party that stands behind her. But a smaller segment has voted against Igor Dodon and like other leaders than Sandu, like Renato Usatîi or Ilan Shor”, explains Dionis Cenusa, a Moldovan political analyst and researcher at the Institute of Political Studies at the Justus-Liebig University in Giessen.

“So, in a nutshell, the votes for Maia Sandu is the run-off is not equal to her real popularity at the moment. This should not mean that things can change if her presidency obtains good results“, Cenusa told GlobalVoices.

Therefore Sandu’s support came from a diverse group, including her competitors from the first round, the liberal and centre-right politicians Andrei Năstase and Dorin Chirtoacă, whose politics are associated with unification with neighbouring Romania, a position widely loathed by pro-Russian voters.

This time, they were joined by an unlikely ally. Renato Usatîi, mayor of Moldova’s second largest city Bălți, took ten percent of the vote in the first round. Usatîi heads Our Party, a pro-Russian populist opposition grouping whose base somewhat overlaps with Dodon’s electorate. But when Usatîi did not make it through to the second round, he called on his supporters to vote “against Dodon”.

Along with the looming threat of COVID-19, Usatîi‘s participation strongly distinguished this vote from the presidential race in 2016. But much remained the same — particularly the candidates’ talking points.

Both campaigns accused the other of corruption. Prominent PSRM politician Bogdan Țîrdea suggested that Sandu’s allies and leading independent media were the agents of the billionaire philanthropist George Soros, while Sandu’s campaign drew attention to a surreptitiously recorded meeting in June 2019 between Dodon and Plahotniuc.

Dodon’s campaign materials played some very real concerns among Moldovan voters about “optimisation”, the shrinking of the state sector which Sandu’s style of politics has advocated. However, the dominant tone was one of a culture war: flyers suggested that Sandu’s election would downgrade the status of the Russian language in Moldova, forbid public celebration of the Soviet Union’s defeat of Nazi Germany, and undermine Orthodox Christian values by legalising same-sex marriage. They proclaimed: “Moldova has something to lose!”

These compelled Sandu to release a Russian-language Facebook video on November 12 in which she dismissed each of these accusations.

Dodon has alleged large-scale electoral fraud, but accepted the election result. He now has no other choice: on November 16, Russian President Vladimir Putin congratulated Sandu on her election victory.

In recent interviews with Russian media, such as TV Rain, Sandu has reiterated her desire to preserve strong ties with Russia, even while breathing new life into the 2014 association agreement with the EU. Her key priority with Moscow, she says, is to restore Moldovan exports to Russia, which have been impeded due to poor relations in recent years.

Vladimir Soloviev, a former Moldova correspondent for the Russian daily Kommersant, writes for Carnegie Moscow that the Kremlin might even be able to find a common language with Sandu. The journalist suggests that Russia may have rested on its laurels in recent years, content to sit back as successive unpopular pro-European governments damaged the EU’s credibility with ordinary Moldovans. But as Moscow invested its hopes in one politician, he remarks, Brussels had embarked on a wider programme to regain that trust, repairing roads and rebuilding schools. And despite the apparent assistance of Kremlin spin doctors in assisting Dodon, a vague appeal against change was not appealing enough.

The symbolism of Sandu’s victory is not trivial, particularly given that she has faced sexist language, attempts to spread falsehoods about her personal life, and criticism from religious figures for being unmarried into her 40s. The hope is that Moldova’s first female president can set a new tenor on equality in public life, which the office’s symbolism of the position will certainly allow her.

Crucially, the role will also allow Sandu to call for snap parliamentary elections, which she has already stated is a priority. The stakes will then be even higher.