Millions of Chileans have been protesting for social concerns for over a year. They called for a new constitution to leave the dark past of the Pinochet dictatorship and regime behind. In a constitutional referendum at the end of October 2020, 78% of the population supported this demand. This is a milestone for democracy in one of the most socially unequal countries in Latin America.

by Veronica Pinilla and Gabriel Alemparte from the magazine entrepiso in Chile.

Chile is a country of geographical extremes, of poets and of good wine. The country is also known as one of the world’s most important suppliers of copper – and for people who have lived through the ups and downs of global geopolitics. Now the Chileans want to leave the history of their regime behind for good.

It all started with a coup d’état in 1973, when a group of generals led by Augusto Pinochet overthrew the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende. Allende was a reform politician supported by socialists, communists and other smaller left-wing groups. As head of state, he pursued the goal of further developing the European-style social democracy.

Social Inequality: The Legacy of Colonialism

Allende’s program provided for the implementation of a far-reaching social policy to fight extreme social inequality within the country. This has its origins in the 18th century, when Chile was a poor and remote Spanish colony. Even independence after 1810 did not change the massive inequality in the distribution of social wealth. A small oligarchy had the available capital at its disposal, and until the agrarian reform of 1970, it also owned land. The majority of the Chilean population remained in a state of marginalization. In the 20th century, the expansion of public educational institutions led to the emergence of a more significant middle class consisting of workers and specialists, who eventually attained more political power.

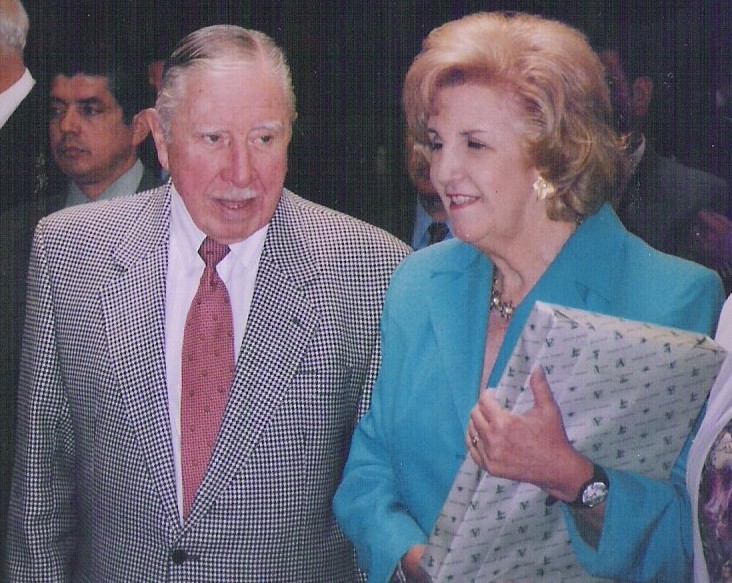

Chile’s former president Salvador Allende, source: Wikimedia Commons/Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional/ CC BY 3.0 cl

Chile: The experiment of neoliberalism

Under Pinochet, Chile was strongly influenced by US interventionism during the Cold War and the economic positions of the Chicago School. These influences were anchored in the 1980 constitution that is still in effect today.

The so-called Chicago Boys were a group of scientists. Their goal was to fight the welfare state, which they despised, with realpolitik. In 1973, they got their chance. In a coup d’état, General Augusto Pinochet overthrew the democratically elected socialist president Salvador Allende. Pinochet created a fascist, economically neoliberal military regime. The Chicago Boys were given a playground in which to live out their economically liberal fantasies.

Dictated by legal representatives of the military junta, it still determines the country’s fate today. This greatly limits the possibility of state intervention. The principle of a “subsidiary state” written into this constitution weakened the country’s social system, especially its health care and education systems. Both were largely handed over to the market. This went along with a strong abuse of power by the ruling elites over the years.

After the coup d’état, Pinochet created a fascist, economically neoliberal military regime, source: Wikimedia Commons/ Emilio Kopaitic

1990: Chile’s path to democracy

After the restoration of democracy in 1990, the democratic governments saw it as their duty to weaken neoliberal structures and reduce the enormous accumulation of power to a small group of big business owners. The Chilean society started to become increasingly politicized. These business owners had benefited from the dictatorship for a long time and were morally very conservative. Many of them received their education in the United States and were influenced by Milton Friedmann’s neoliberal theory.

Democracy in Chile was and is reliant on the long process of dismantling the political structures left behind by the military dictatorship. To this day they are set down in the 1980 constitution, which always favored a minority that was close to the ruling regime. This protected Pinochet and his legacy for a long time. The return to democracy was not easy.

Concertación: Coalition for democracy, protection for Pinochet

Social Democrats, Christian Democrats, Socialists and Liberals founded the alliance Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia (“Coalition of Parties for Democracy”) in 1988, which existed until 2013. In contrast, there was a parliament and an electoral system that favored conservative forces and largely solidified the legacy of the dictatorship. The protection of Pinochet was silently agreed. Nevertheless, the post-dictatorship governments managed to make progress in some areas. Chile became part of the globalized world. Today the country has one the largest number of free trade agreements concluded, including with Asia, the European Union, the United States and South Korea.

Chile: The Pinochet constitution remains an obstacle to social and democratic progress

Culturally, the conservative legacy of the regime as well as the influence of the Vatican could be pushed back in some areas. In 2004 Chile – one of the last countries in the world to do so – passed a law regarding divorce. Issues such as abortion for therapeutic reasons or the equality (passed a law in 2017) of illegitimate children (1998) were de-tabooed. In addition, the government established programs in social and health care as well as in child and youth protection. This has helped to reduce the poverty experienced by the Chilean people to some extent. Poverty decreased from 34% in 1990 to 7.4% in 2017, but the symptoms of inequality continued to be part of a society where rights do not have the same access for all, something deeply felt by the new generation born in democracy after the regime.

There have been several constitutional amendments over the past 30 years. The most important one was in 2005 under the presidency of Social Democrat Ricardo Lagos. However, the lack of democratic legitimacy of the 1980 constitutional text continued to cause deep divisions among the Chilean population. The legacy of the regime constituted a major obstacle to social progress and the development of a democratic welfare state.

Conservatives block further reforms, Chileans demand justice

Large student protests marked the first government of Michelle Bachelet in 2006. A new generation stepped forward, born in democracy. A generation, ready to overcome the traumas of the regime and fight for a better future. The students demanded free education and fair pensions. Poverty among the elderly is a structural problem in Chile. This problem is being intensified by demographic change and an aging population. The gap between those who can afford an acceptable pension and health insurance and those who cannot is becoming bigger and bigger. Bachelet, the first socialist woman to become President of the Republic, planned far-reaching reforms in her second term of office (2014-2018). These reforms included a constitutional reform, too. However, the conservative sectors in Congress and the economic elite ultimately prevented this from happening.

When Sebastián Piñera, a center-right politician supported by Pinochetists, became president in March 2018, he postponed or stopped many of these projects. It was said, that he wanted to avoid the threat of economic instability that these changes might cause. In October 2019 there were strong protests following a series of wrong decisions by the Piñera government. In particular, he increased public transportation fares. The brutal actions of the police and a profound loss of confidence in politics led to a social explosion.

Street protest left people injured and dead. These human right violation have been denounced by various national and international organizations, the complaints were even able to reach the international criminal court. As a result of this October 2019 uprising, Congress finally initiated a process to repeal the 1980 Constitution.

Protests in Ñuñoa, Chile for a constitutional referendum in 2019.

October 25, 2020: 78 % of Chileans want a new constitution

On October 25, 2020, more than 7 million Chileans went to the polls during the constitutional referendum. With an overwhelming majority of 78% they voted in favor of a new constitution, in the form of a Constitutional Convention. This means, that an elected assembly will prepare the new constitution. This convention should be composed of 50% women and 50% men. The people will elect them directly and independently of parliament. As a final step, the new constitutional text must be approved in a so-called exit referendum.

However, there is still a long way to go. In April 2021 the Chileans will elect their representatives, which will take charge of drafting the new constitution. It is then important to continue making progress while the big corporations and other powerful actors can still prevent change. The road is long, but the Chileans’ confidence and hope for building a socially fair and democratic society is growing ever stronger.