By Maxine Lowy (i)

Less than thirty minutes before polls closed, and another half hour before the first official count, increasing numbers of people circulated along the sidewalks of Huechuraba, heading for the Civic Plaza, a vast open space where concerts, fairs and demonstrations are held in this working-class community in northern Santiago. Soon, hundreds of people filled the esplanade, the atmosphere reverberating with a cacophony of vuvuzelas, cars honking, and fireworks. A year ago, more than a million people poured into the streets of Santiago calling for societal change. Now, this Sunday night, October 25, people throughout the country were celebrating the victory of the first step of a process that will culminate in a new constitution, and disperse the shadows remaining from dictatorship.

Yet, the neighbors of Huechuraba had all the more reason to celebrate.

In Huechuraba, Apruebo (I Approve) won with 81% of the votes, surpassing the national percentage by three points. Moreover, the notable 63% of the electorate who voted in Huechuraba, positioned it sixth nation-wide in voter turn-out, a full seven points higher than the national participation average. The number of people who turned out to vote surpassed by nearly 9% voter participation in the last presidential election of 2017.

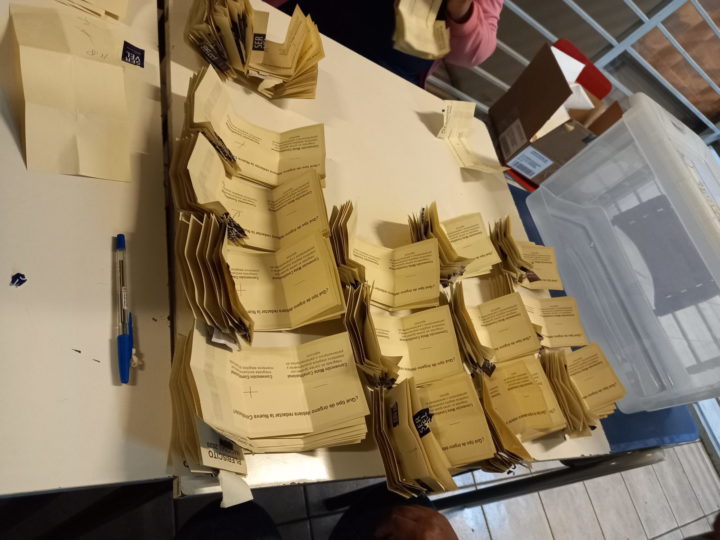

Door-to-door campaigning, flyers, flag waving, informational meetings at social distance, and handing out voter kits containing a mask, gel and a blue pen at the open air market were some of the activities that visibilized the plebiscite. Beyond the possible effectiveness of such campaign strategies, the history and personal experiences of many neighbors of this community may have made them particularly receptive to the message of change. Last year’s social movement awakened people to the fact that a certain extent of their marginalization and unequal horizons are rooted in the constitution that perpetuates the dictatorship’s vision of market over people.

Some speculate this is what spurred massive voter turn-out in some regions of Chile and Huechuraba in particular.

That’s how Ricardo, 59, and his wife Lidia, 49, see it. They brought three of their children to celebrate at Civic Square Plaza. “I am so moved, so happy, about what has been achieved, and that my children’s future will change,” expressed Ricardo, a housepainter. His greatest aspiration is “first of all, dignity. There has to be dignified treatment and work for all Chileans.” The couple has five children, two of whom graduated from universities, not just with diplomas but saddled with debts until they are 35 years old.

“The only way to access higher education is through the governmental loan program. A similar inequality affects health care. If you don’t have the money, you cannot count on a good health care service. You have to wait, wait, wait,” says Lidia. “Last year we lost two relatives to cancer, and we know that it was due to inequality: a lack of prompt diagnosis, lack of treatment, lack of opportunity to access adequate treatment. That is fatal.”

At one of the largest of the 10 polling places in the municipality, the Huechuraba Educational Center, in sight of the Civic Plaza, more than 8,000 of the 10,511 people registered at this location turned out to vote. The line to enter the building wound around the corner, extending several blocks, with social distance between people. Where, in pre-coronavirus days, 600 students studied – at the municipality’s only public secondary school – 158 voting tables were installed in classrooms, in the gym, and along the corridors.

Laura Acuña Baeza, who monitors compliance with Covid-19 protocols, was a poll watcher at this location. While gathering results from polling tables, she paused a minute to share her thoughts.

“Seeing so many young people and seeing elderly people on crutches evoked all kinds of emotions throughout the day. Sometimes I wanted to cry, at other times shout from joy. Young people finally realized that they could lead this country along a road to change, and the rest of us came on board,” Laura noted.

Laura is 50 years old, the same age as her neighborhood, in what is known as La Pincoya. When she was born, her parents had spent four months living in a tent, after participating in a land occupation along with hundreds of other people, demanding housing. One of her most salient memories is of the brick campaign, when every family contributed two bricks to help build a stage at her school. The bricks were made from straw mixed with clay, taken from the hills of Huechuraba (“Place of Clay” in the Mapuche language). School infrastructure improvement is the responsibility of the state. But this was 1976, dictatorship, and the military had no interest in investing in basic services. In light of governmental apathy, the neighbors decided to build the stage themselves. It took a year to build, but the experience strengthened confidence in their own capabilities to achieve things.

Seeing the long lines to vote Sunday triggered Laura’s recollection of 1988, the first time she voted, in an election that halted the dictatorship’s prolongation. The plebiscite of 1988 and that of 2020, were “very similar processes,” she believes. In both cases, Chileans reached the ballot boxes after intense protests, led by the younger, more courageous generation, who confronted immense power and endured brutal repression. The systematic human rights violations committed in both eras brought international condemnation of Chile.(ii) That set of circumstances helped create the political conditions that enabled the referendums.

“Imagine how moved I was, remembering what I experienced when I was 18, and now that I’m 50, to see young people in a similar struggle. I hope young people have realized that they are capable of determining the political outlook of this country, by casting a vote. They – not us- began this struggle. I just hope they don’t ditch the fight, because it takes longer than they want, because we really will achieve concrete change.”

While Laura is talking, people cheer when yet another voting table confirms that Apruebo has won.

At voting table 19V, another poll watcher, artist Alex Olave, 34, records the results that the table president announces, again and again, after opening the folded and sealed ballots with the votes marked inside: “Constitutional Convention.” At this table where 174 people voted, 141 voted Apruebo.

At this point, the four voter assistants, assigned randomly to this table by the Voter Registrar, have spent twelve hours together, and they still have to sign the envelopes containing the ballots. A voter assistant from another table comments, “We were happy at the end of this long day. None of us mentioned our views, but clearly we were all for Apruebo. When it was time to go home and part ways, I felt a touch of nostalgia, after all we had shared.”

“I am so moved because a sort of complicity emerged among the different people who comprised this table,” says Alex. “There was a shared sense of having done something important, necessary, and a shared commitment.”

Like many raised in this municipality, Alex has enjoyed long walks in the hills. “The Carmen canal connects two Huechurabas, divided by Punta Mocha hill. When you walk along the canal, you see rusted tin roofs below in the oldest section. Near the border of the canal, you see shantytowns, and flimsy huts. Closer to the other side, you begin to see tall buildings, condominiums, swimming pools, beautiful colors. The separation between the real estate bubble on the western section and the shantytowns that still exist in the oldest section is the best example that illustrates the inequality in our country, reflected in this municipality.”

Alex’s parents were community activists but now live outside Chile. After the 1988 plebiscite, Alex notes, “They were sure things would change. My father became totally disillusioned that the promises of change were not kept. It hurts him to this very day.” That motivated Alex to volunteer as poll watcher. “For years I heard how my parents fought so hard during dictatorship; for their sake I had to participate today.”

Regarding his own expectations, Alex says, “This democratic process has to reflect the desires of the Chilean men and women who live here. And it must bring about the changes people need.”

Crossing the street to Civic Plaza, with its memorial to 28 neighborhood people murdered or forcibly disappeared by the dictatorship, the celebration continues. But, in a flash, the festive mood abruptly ends. Police are firing tear gas into the crowd, and people run. “You see?” says Ricardo, “People were happy, expressing themselves peacefully. Like I said before, above all else, we need dignity.”

(i) Maxine Lowy, journalist and translator, lives in Huechuraba.

(ii) In 1987, one year before the 1988 “SI y No” referendum, there were 31 deaths committed by agents of the state, documented by the National Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report, whereas in just the first 28 days after October 18, 2019, official records confirmed 23 deaths and 2,500 injuries.