Testifying at Assange’s extradition hearing on Wednesday, Ellsberg said the WikiLeaks co-founder would be denied a chance to defend himself if sent to the US for a trial, noting that, like in his own case, Assange would not be permitted to argue his publications were in the ‘public interest.’

“I observe the closest of similarities to the position I faced, where the exposure of illegality and criminal acts institutionally and by individuals was intended to be crushed by the administration carrying out those illegalities,” Ellsberg told the court.

[Assange] cannot get a fair trial for what he has done under these charges in the United States.

WikiLeaks disclosures – such as the grisly ‘Collateral Murder’ video, showing an American gunship firing on Iraqi journalists – have exposed evidence of war crimes, the famed whistleblower went on, arguing that Americans had a right to know what their government had done in their name.

“I was acutely aware that what was depicted in that video deserved the term murder, a war crime,” he said of the ‘Collateral Murder’ footage, adding in his written testimony that the video confronted citizens with the “reality of our war.”

The American public needed urgently to know what was being done routinely in their name, and there was no other way for them to learn it than by unauthorized disclosure.

On cross examination, a lawyer acting on behalf of Washington, James Lewis, argued that Assange was not being prosecuted for the infamous video in particular, but rather for publishing the military’s classified rules of engagement in Iraq, among other things. Ellsberg replied that disclosing the rules was necessary to demonstrate the war crimes committed in the video, adding that instead of punishing the soldiers involved, the government was now prosecuting the man who revealed evidence of their wrongdoing.

Lewis also challenged Ellsberg’s comparison to his own 1971 ‘Pentagon Papers’ leak – in which he passed 7,000 pages of classified documents on the Vietnam War to the press – observing that Ellsberg had withheld information from the disclosure. However, the whistleblower said he had not redacted a single name of an informant or covert CIA agent, and that unlike himself, Assange had withheld some names, and even approached the Defense and State Departments for help in making additional redactions. He was denied, Ellsberg said.

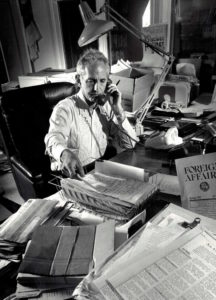

Daniel Elsberg, in his office, working on his latest book, a photo from his official website.

“So it’s all the governments’ fault then,” Lewis shot back.

“Yes, they bear a heavy responsibility,” Ellsberg responded, adding that the government’s sudden concern about redactions was “highly cynical” given that officials had rebuffed Assange’s request for assistance.

Ellsberg – a former strategic analyst for RAND Corp. who regularly worked with the State Department and the Pentagon between the 1950s and 1970s – disclosed evidence that the US had illegally expanded its bombing campaign on Vietnam into neighboring Laos and Cambodia, as well as how American officials in four administrations had misled the public about the war effort. Following the leak, Ellsberg was charged with 12 counts under the Espionage Act, the same law underpinning most of Assange’s charges, and faced up to 115 years in prison. His case was ultimately dropped after it was revealed that the government had gathered evidence against him illegally.

Assange remains in custody at London’s maximum security Belmarsh prison as he awaits a verdict in his extradition case, which is set to last into early October. If sent to the US for trial, the WikiLeaks publisher faces a 175-year prison sentence, charged with 17 counts linked to espionage and computer intrusion over his role in disclosing classified material.