Indigenous women in Canada suffer high rates of violence

In the Canadian winter of 2002, passers-by walking through Vancouver’s Downtown East Side could see Rebecca Belmore, from the Indigenous Anishinaabe Nation, nailing her long red dress to a telephone pole. She struggled to free herself, and then once released, her dress hanging in tatters and her underwear exposed, she silently read the names of the missing women that she had written on her arm. She concluded her performance by shouting the names one by one.

Belmore is a multidisciplinary artist, and this is part of her work, called “Vigil”. Through it, she commemorates the lives of the missing and murdered Indigenous women who have disappeared from the streets of Vancouver. She wants “to let each woman know that she is not forgotten: her spirit is evoked, and she is given life by the power of naming”.

The performance, now shown in a video in Belmore’s exhibits, may surprise distracted observers, but the reality is that in Canada — frequently ranked at the top of lists rating global quality of life – Indigenous women suffer high rates of violence. In 2014, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) confirmed that 1,017 indigenous women have been murdered and that 164 have disappeared since 1980, even though indigenous women only constitute 4.3 percent of the country’s female population.

“Vigil”, by artist Rebecca Belmore. Photo taken by the author at the Exhibit “Rebecca Belmore: Facing the Monumental“, at Montreal’s Musé d’art Contemporain, in 2019

Research conducted by the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) has found that aboriginal women are almost three times more likely than non-aboriginal to be killed by a stranger. Indigenous women and girls are either murdered by strangers (16.5 percent of the time), acquaintances (17 percent), or a partner (23 percent).

NWAC’s research concludes that aboriginal women experience violence by both aboriginal and non-aboriginal offenders, the vast majority of whom are men. It also reveals that only 53 percent of murder cases involving aboriginal women and girls have resulted in charges of homicide — well below the 84 percent national clearance rate for homicides in the country.

The association Quebec Native Women (QNW) has stated that before the arrival of Europeans, indigenous women played an essential role in the health, spirituality, education, economy and politics of their communities. This dynamic changed drastically through the imposition of “European patriarchy” policies, which have continued to the present.

According to researchers from various Canadian universities, such as Marie-Pierre Bousquet and Sigfrid Tremblay, systematic colonialist policies imposed by the Canadian federal government have sought to assimilate indigenous people into a Euro-Canadian lifestyle, thereby eroding native culture and identity.

One such policy is the Indian Act, in force since 1876, which dictates how the federal government rules on matters related to indigenous people. Originally aimed at the progressive extinction of Canada’s indigenous population, anthropologist Pierre Lepage says this law still affects their legal capacity and undermines their autonomy.

QNW calls this “erasure ideology”, which began with “the progressive theft of the territories” of indigenous women and forced them to go “from loss to loss” of resources, autonomy, identity, and culture.

For QNW, the consequences of colonialism include the disadvantageous socio-economic context in which indigenous women live today, which in turn leads to increased risks to their very existence. In fact, violence against indigenous women in Canada has been called genocide.

To overcome their suffering, indigenous women have denounced and resisted a colonialist, racist, and sexist system. Slowly but surely, art has become an important tool for both expression and catharsis, allowing them to reclaim an alternative, incisive, and heartbreaking version of their history while coming to terms with society’s role in their current challenges as well. Here are some of their most stirring artistic expressions:

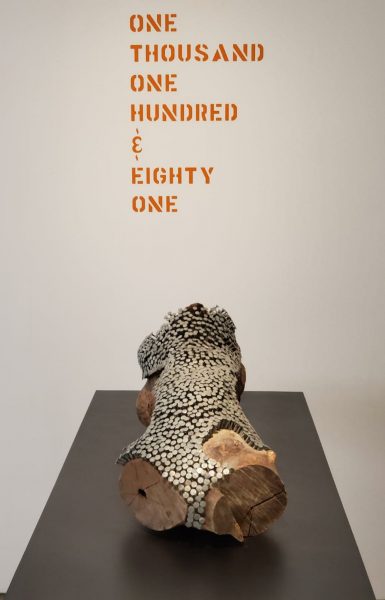

“1181”, by Rebecca Belmore (2014)

Nails — all 1181 of them — were hammered by Belmore onto a tree stump, each one representing a case of murdered and missing indigenous women recorded by police statistics.

“1181”, by artist Rebecca Belmore. Photo taken by the author in the Exhibit “Rebecca Belmore: Facing the Monumental“, at Montreal’s Musé d’art Contemporain in 2019

“Fringe”, by Rebecca Belmore (2007)

The artwork is a photo of a half-naked woman lying on her side, her back to the camera, on which she has a sewn scar running from her shoulder all the way down, and from which red beads, symbolic of blood, are spilling out.

Belmore says of the piece, “[I]t’s the body that doesn’t disappear.” In her work, the artist often depicts the female body with healing wounds, such as those carried by many survivors, to demonstrate the resilience of indigenous women.

“Walking with our Sisters”, by Christi Belcourt (2012-present)

Artist Christi Belcourt, a Métis, who is mixed race (white and indigenous), produced an installation which places about 1,763 pairs of fine beaded vamps of moccasins on the ground, each one representing a missing or murdered woman, as well as the children who never returned home after going to residential schools, responsible for the systemic separation of indigenous children from their families and culture.

“REDress Project”, by Jamie Black (2011)

This installation involved the collection of 600 red dresses, a color which symbolised protection against violence, through community donations. Black, who like Belcourt is a Métis artist, wanted the work to be an aesthetic response to violence against women. Through the absence of the female bodies who should wear the dresses, she creates a visual reminder of the great number of women who are absent.

Images of the “ReDress” project. The photo on the left was taken by Jamie Black and the one on the right, by Sarah Crawley. They are used with permission.

“The Three Graces”, by Kent Monkman (2014)

Monkman, a Cree and Irish artist, is known for creating strong visual criticism that embeds alternative versions of colonialism’s dominant narrative, all from a personal and indigenous perspective.

Through irony, Monkman denounces violence against indigenous women, including the sexual exploitation of and prejudice against those working in the sex industry. His painting “Le petit déjeuner sur l’herbe”, for example, shows naked prostitutes sprawled in front of a hotel in Winnipeg, a province where around 70 to 80 percent of street prostitution is carried out by indigenous women.

In “The Three Graces”, Monkman’s version of Rubens’ homonymous painting, the goddesses of charm, beauty, and creativity are represented as three indigenous, body-diverse-women. With this piece, Monkman honors the “missing and murdered sisters”. “In Canada,” he said, “there is a lot of violence against Indigenous women […] over 1,300 missing and murdered.”

As an outspoken critic of mainstream society’s lack of understanding of indigenous people, Monkman also strives to highlight the power of indigenous women’s femininity, which is highly respected in indigenous tradition.

Indigenous art is therapy for both individual and collective suffering. According to the Health and Social Services Commission, it promotes resilience and has a positive effect on identity, self-esteem, emotional well-being, and physical and mental health. Art, as an educational tool, could also serve to hold the Canadian government accountable for its policies and promote an authentic reconciliation process.

Written by Sabrina Velandia