This Thursday, July 9, is the 65th anniversary of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, a ground-breaking event that gave rise to the establishment of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs in 1957 (awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995) and the World Academy of Arts and Science in 1960. This week also sees two other significant, nuclear disarmament related anniversaries: July 8 is the date in 1996 when the International Court of Justice delivered its historic judgement on the illegality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons. And July 10 is the anniversary of the state-sponsored terrorist bombing of the Greenpeace ship the Rainbow Warrior in Auckland harbour, New Zealand to prevent it from protesting against the French nuclear tests at Moruroa. The ensuing dispute between France and New Zealand was eventually settled through a mediated ruling by the UN.

These three anniversaries provide inspiration to consider the roles of science, law and diplomacy to advance peace, security and nuclear disarmament.

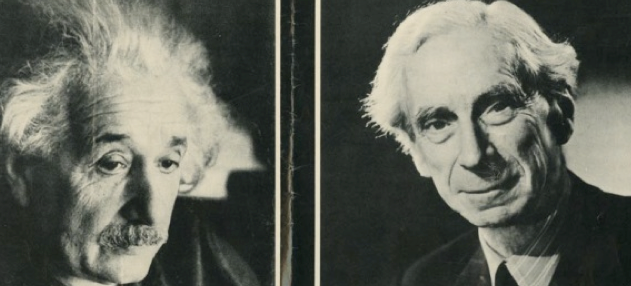

Russell-Einstein Manifesto:

In May 1946, Albert Einstein sent a telegram appeal to several hundred prominent Americans calling for establishment of an organisation “to let the people know that a new type of thinking is essential” in the atomic age. Einstein wrote in his telegram: “The unleashed power of the atom has changed everything save our modes of thinking and we thus drift toward unparalleled catastrophe.” In Einstein’s view, “old thinking” included the belief that wars are inevitable; that the best defense is a good offense; that any military build-up by an enemy must be matched or exceeded; and that wars can—indeed, must—be fought against hateful and dangerous concepts such as terrorism and communism. The new thinking was that global governance, conflict resolution and common security must replace preparations for war.

This thinking was outlined more comprehensively in the Russell-Einstein Manifesto which opens with the question: ‘Here, then, is the problem which we present to you, stark and dreadful and inescapable: Shall we put an end to the human race; or shall mankind renounce war?’ The answer was of course that we must put an end to war. ‘We have to learn to think in a new way. We have to learn to ask ourselves, not what steps can be taken to give military victory to whatever group we prefer, for there no longer are such steps; the question we have to ask ourselves is: what steps can be taken to prevent a military contest of which the issue must be disastrous to all parties?’

The Manifesto calls for an ‘agreement to renounce nuclear weapons as part of a general reduction of armaments’ but notes that this would not afford an ultimate solution. ‘Whatever agreements not to use H-bombs had been reached in time of peace, they would no longer be considered binding in time of war, and both sides would set to work to manufacture H-bombs as soon as war broke out, for, if one side manufactured the bombs and the other did not, the side that manufactured them would inevitably be victorious.’ As such, the Manifesto re-affirms a number of times that nations must give up the option of war itself and to use ‘peaceful means for the settlement of all matters of dispute between them.‘

An interesting point is that these were scientists – not politicians – who came together to call for and end to nuclear weapons and war. They appealed in particular for all of us – whether world leaders or regular citizens – to look beyond our national identity in order to recognise our common humanity. ‘we want you, if you can, to consider yourselves as members of a biological species which has had a remarkable history, and whose disappearance none of us can desire… We appeal as human beings to human beings: Remember your humanity, and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open to a new Paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.’

ICJ 1996 Nuclear Weapons Case

On July 8, 1996, the International Court of Justice rendered its decision on a question asked by the UN General Assembly on the legal status of nuclear weapons. The ICJ affirmed (by split vote) that the ‘threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, and in particular the principles and rules of humanitarian law;’ and that ‘There exists an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all its aspects under strict and effective international control.’ The Court conceded that there might possibly be a legal use of nuclear weapons if the very survival of a state was at stake and a nuclear weapon could be used in that circumstance that did not breach IHL (i.e. against a military target far from civilian centres with minimal radioactive fallout), but even then the Court indicated that it had no evidence to demonstrate that such as use was possible. Rather, the court noted that ‘The destructive power of nuclear weapons cannot be contained in either space or time.’ In essence that ICJ opinion has rendered all uses of nuclear weapons illegal, unless a state can prove that there is a use that could confirm to international law.

The significance of the ICJ decision is that it affirms customary international law which applies to all states, as compared to treaties which generally only apply to States parties to those treaties. This means the obligation to achieve nuclear disarmament affirmed by the ICJ is applicable not only to States parties to the Non-Proliferation Treaty, but also to those that are not parties, i.e. India, Israel, North Korea and Pakistan. It also means that the general prohibition against the threat or use of nuclear weapons applies to all States, including those that are not parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, i.e. all the nuclear armed and allied states in addition to some non-nuclear States who have not joined the TPNW.

This decision was strengthened further by the UN Human Rights Committee in 2018, when they affirmed in General Comment 36 on the Right to Life that ‘The threat or use of weapons of mass destruction, in particular nuclear weapons, which are indiscriminate in effect and are of a nature to cause destruction of human life on a catastrophic scale is incompatible with respect for the right to life and may amount to a crime under international law.’ Although such a decision by the UN Human Rights Committee is not as authoritative under international law as a decision from the International Court of Justice, it adds legal and political weight due to the fact that all the nuclear armed States with the exception of China are parties to the International Covenant on Social and Political Rights, which includes the Right to Life and upon which the General Comment 36 was made.

Rainbow Warrior bombing and resolution

The Rainbow Warrior bombing, the subsequent international conflict between France and New Zealand, and the resolution of this conflict through the United Nations demonstrate the value and utility of the UN and its mechanisms under Article 36 for the resolution of international conflicts, including those relating to nuclear weapons and acts of aggression.

On July 10, 1985, the Rainbow Warrior peace boat operated by Greenpeace, was destroyed by limpet mines secretly attached to the hull of the ship below water by French divers from the Direction générale de la sécurité extérieure (DGSE – French secret service) while the boat was moored in Auckland harbour (New Zealand). The French government destroyed the boat to prevent it from sailing to Moruroa (Polynesia) to protest against French nuclear tests. One person was killed in the explosion. New Zealand caught two of the DGSE agents who were tried and convicted of manslaughter. In response, France initiated an economic boycott on New Zealand. Where-as the United States was responding to state sponsored terrorism of Libya at the time by bombing Tripoli, New Zealand chose a diplomatic path and utilised the mechanisms of the UN, in particular the mediation services of the office of the UN Secretary-General, to resolve the international dispute. Following the resolution, New Zealand as a sign of good-will, established a New Zealand-France Friendship Fund to help restore good relations between the citizens of the two countries, which had been soured in particular by the French actions. The fund supports arts and cultural exchanges between France and New Zealand.

This was not the first time that New Zealand has utilised the United Nations mechanisms for security and conflict resolution. In 1973, New Zealand, Australia and Fiji launched cases in the International Court of Justice against France over it’s atmospheric nuclear testing program which was releasing dangerous radionuclides in the Pacific. The case was instrumental in moving France to end its atmospheric testing in 1975 – and a similar ICJ case in 1995 helped end France underground testing and move France to close down its nuclear test sites in the Pacific. The success in using UN mechanisms by New Zealand was one of the factors that led New Zealand to reject the illusory security of nuclear deterrence, to which it had subscribed to under extended nuclear deterrence relationship with the US, and adopt instead the most comprehensive nuclear abolition legislation in the world in 1987.

Conclusion

The ideas in the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, and the examples of the ICJ nuclear weapons case and Rainbow Warrior dispute, reflect key aspects of the UN Charter including Article 2 on the prohibition of the threat or use of force in international relations and Article 36 on processes and mechanisms for the peaceful resolution of conflicts. In 2020, the 75th anniversary of the UN, civil society organisations around the world are calling for reaffirmation and better implementation of these articles – and especially for all UN members to subscribe to the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice to resolve international disputes when diplomacy has not succeeded. Only 74 countries have done so to date.