Uganda’s COVID-19 experience underscores the seemingly universal opportunism of authoritarians amidst crisis, as well as opportunities for resistance.

Eight young Ugandan men swarmed the streets of a bustling-yet-militarized Kampala. They were banging empty saucepans to demand food, which the government had promised to distribute. For this June 17 noisemaking “crime,” police packed them into a tiny cell at Kitalya Maximum Security Prison.

The arrests and the politically motivated killings won’t slow down anytime soon. As elections near, dictator Yoweri Museveni’s armed forces — cushioned by the ongoing financial support of the U.S. government — enjoy conditions of impunity as they attack starving women and youth protesting for their survival.

Since the 2009 Kabaka Riots, Uganda has witnessed a gradual but steady surge in resistance to Museveni’s autocracy. This struggle was recently offered a boost of morale as Black Lives Matter protests in the United States inspired a surge of resistance in Africa.

Even so, Ugandans have been hard at work fighting deplorable circumstances long before the straw broke the camel’s back. The story of the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda is quite a unique one, but it underscores the seemingly universal opportunism of authoritarians amidst crisis, and reveals that this opportunism can be resisted.

Armed deployment as lockdown begins

On March 19, the first full day of Uganda’s COVID-19 lockdown, I ventured on foot to my nearest trading center to stock up on supplies for our household. The street bustle was lighter than usual, but not substantially so. Supermarkets were equipped with washing stations, and most staff were wearing masks.

A motorcycle raced by, sharply cutting off my footpath. The driver slammed on the breaks at the now non-operational minibus stop. He and his passenger, as it turned out, were police officers.

“Didn’t you guys hear the boss’ directives last night?” I teased while continuing on my way. “No motorcycle is to carry people — only cargo!” I got a few laughs from onlookers who overheard my lighthearted civilian enforcement of Museveni’s lockdown decrees. But the police officers were not amused.

When I came out of the nearby supermarket five minutes later, more police had arrived to patrol the area. Seeing them armed with AK-47s — but no masks and standing shoulder to shoulder — I couldn’t help but offer more humor to diffuse the growing feeling of a military dystopia.

“Guys, the big man said no large groups! Protect yourselves by keeping a distance! You don’t want to take this virus home to your relatives.”

The tenseness of the trading center loosened with a few giggles, until one of the officers barked in my face, saying I wasn’t supposed to be out in public.

Unpleasant as it was, it was helpful to see how the authorities were enforcing Museveni’s new lockdown measures because later that day we intended to test them. Some neighbors and I were planning to deliver clean drinking water and snacks to the victims of a shoddy, opportunistic quarantine — a mismanaged detainment center for travelers arriving at Entebbe International Airport. Our goal was to expose the wretched conditions and the private profiteering that was going on at the expense of the travelers, even healthy ones. It was a sign of how Uganda’s dictator, in power for the past 34 years, would exploit this new global health crisis. Sure enough, rumors of swindling a half-billion-dollar International Monetary Fund loan ensued soon thereafter.

A dictator’s dream come true

Uganda had been relatively insulated from the pandemic, especially in March. The outbreak of COVID-19 traced the routes of the global economy, spreading especially in those areas of hypermobility. Uganda is a largely agrarian inland country without a large international transportation hub. Currently, only less than a thousand positive COVID-19 cases have been registered to date, none of them thus far fatal.

What has been fatal, however, are the autocratic measures imposed upon Ugandans. Pregnant women and the sick are dying because they can no longer reach health centers to give birth under professional care and treat basic curable illnesses like malaria. Securing the proper paperwork to enable them to travel beyond police checkpoints to obtain professional medical assistance is a seemingly impossible nightmare for most. As a result, it is likely that more people have died from the harsh lockdown measures than those that currently test positive for COVID-19.

Museveni’s ban on private transportation began April 1. Most Ugandans use public transportation, which had already been restricted, but the total ban on all transportation of passengers (as opposed to cargo) ushered in a surge of existential threats. Adding insult to injury, those in need of medical services would have to get permission from their Resident District Commissioner, or RDC — the person heading districts of hundreds of thousands and sometimes millions of residents — to travel to the nearest professional health facility. Otherwise, the vehicles of their transporters would be impounded at police checkpoints.

Dismantling a predatory quarantine

As the COVID-19 outbreak spread globally and a few cases began popping up around East Africa, Uganda’s Ministry of Health opened a quarantine at Central Inn, a private hotel in Entebbe, three miles from the international airport.

Central Inn and the Ministry of Health agreed that those under quarantine would foot their own bills — upward of $100 per day. This resulted in Ugandans and foreign nationals being bussed to Central Inn without warning and being held against their will at their own expense. An alliance of travelers and Ugandans returning home — led in part by quarantined political cartoonist Jimmy Spire Ssentongo — resisted the Ministry of Health’s neglect by sleeping in the hotel lobby. No extra beds or mosquito nets were brought to this small space for those quarantined. Clean water and meals were being sold at four times the market price. Neither armed forces patrolling the quarantine nor hotel staff were equipped with the proper personal protective equipment. The so-called quarantine became a petri dish for a COVID-19 outbreak, among other diseases.

Ssentongo sent a message to Merab Ingabire — a management member at the movement support network Solidarity Uganda — requesting water. He also noted that the quarantined either could not afford private rooms or had refused them on principle, even as sickness spread without due attention from the Ministry of Health.

As neighbors to the quarantine, we pitched in and brought the water and a few snacks to the gate of Central Inn. Here we were met by armed forces and a man from the Civil Aviation Authority who asked upon seeing my white skin whether we were from the Ministry of Health.

Phil Wilmot waiting outside the gates of Central Inn, where quarantined travelers were in need of water and other supplies. Facebook/Solidarity Uganda

“We have come to deliver water to those quarantined here who have not been given rooms,” I explained.

The man had a difficult time finding grounds to refuse this delivery and, before he could, we quickly unloaded our contributions at the gate. Ssentongo met us there, and we were then allowed to stack the items on the ground for the quarantined to bring back to their fellow residents occupying the lobby.

That day, publicity about the situation at Central Inn grew. The Ministry of Health convened emergency meetings and took action to begin disbanding the mismanaged quarantine. Some support from state budgets trickled in, and the financial burden no longer solely fell upon those unfortunate enough to arrive in Uganda at the wrong time.

Yet, even when the Ministry of Health finally agreed to deliver on its mandate, it did so reluctantly. Some under the 14-day quarantine were still forced to foot their own bills. In several cases, the quarantine was prolonged due to test results that had been mishandled and lost. Although several in quarantine showed no symptoms after 14 days, they were still being forced to pay room and board for an indefinite period of time so that additional tests could be administered.

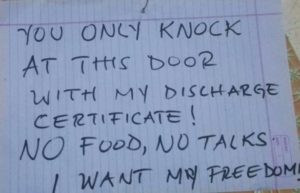

A foreign national under quarantine posted this message to their door at Central Inn. (Twitter/@bwesigye)

Soon foreign nationals started posting videos of themselves pledging a hunger strike. They refused to answer their doors, except for a health certificate allowing their exit. Using toilet paper and scrap paper, they posted demands to their doors and, after days of protests, most were eventually released.

But these activists weren’t the only ones in Uganda running on empty stomachs.

A hungry people in the region’s breadbasket

Uganda has the most fertile land in East Africa, and farmers comprise the majority of the population.

The urban poor — nearly one in every four Ugandans — have had a difficult time feeding themselves under lockdown. Museveni had threatened murder charges to any rival politicians who attempted to distribute food, while his own convoys circulated communities doing exactly this while advertising the ruling party.

In solidarity with the hungry, Member of Parliament Francis Zaake openly violated presidential orders by distributing food within his Mityana constituency, resulting in his arrest and brutal torture. His grotesque wounds were declared “self-inflicted” by a Ministry of Internal Affairs report to parliament.

Nonviolent acts of desperation have been waged by the hungry across the country. Sex workers are among the better organized urban poor of Uganda, and in the northern Ugandan towns of Gulu and Lira sex workers received foodstuffs from local government leaders after threatening to reveal the identities of their clients, many of whom are government officials.

Meanwhile, in Kampala, the relentless protester Nana Mwafrika held three consecutive days of arrestable public actions demanding food. Authorities eventually gave in and offered her family a supply. This triggered an outpouring of contributions from other well-wishers, which Mwafrika then redistributed to needy families. Days later, she took to the streets with activist-academic Stella Nyanzi and events promoter Andrew Mukasa, banging empty pots until their violent arrest.

In addition to empty saucepans, stones are becoming another symbol of hunger across East Africa. After a Mombasa woman cooked stones for her family, another woman in Mbale, Uganda adapted this as a protest tactic at the office of her RDC. The tactic migrated from eastern to western Uganda, including communities of Kamwenge, Kyenjojo and Isingiro, where whole communities then converged for “feasts” of stones.

Political history teaches us that hunger unites revolutionary forces. From the French Revolution to Sudan’s 2018 bread subsidy cuts, people power has often been fueled by those with empty stomachs.

All Black Lives Matter

While the George Floyd protests sparked calls to defund police departments in U.S. cities starting in early June, communities across East Africa began to protest their own police states. This was in large part due to the 20 unarmed citizens killed by armed forces in Kenya and Uganda — both recipients of U.S. funding — while enforcing so-called COVID-19 protective measures.

Kaepernick-style kneeling actions took place at the U.S. Embassy in Nairobi — organized jointly by members of Nairobi’s Social Justice Centers, Americans and other foreign nationals living in Kenya. These peaceful actions proposing U.S. financial sanctions on Ugandan and Kenyan police forces and militaries led to arrests in both countries, including 15 Black Lives Matter activists in Uganda at a single protest.

The spirit of resistance spilled into other grievances of Ugandans affected by the pandemic. On June 10, business tycoon Sudhir Ruparelia fired the entire staff of his radio station, Sanyu FM, in response to their sit-down strike against his 25 percent paycut. The former employees retaliated by temporarily seizing control of the Sanyu FM Twitter account, threatening a lawsuit and causing embarrassment to the politically-connected Ruparelia, notorious for leveraging his political connections to steal land for luxury hotels.

In the same week, activists in Amuru pledged to resume direct action against businessmen driving deforestation in their communities, despite curfews that complicate the logistics of their blockades and resource repossessions.

Finding solutions within

According to famed theorist Paulo Freire, one of the best ways to begin to solve a problem is by engaging in discourse and listening to those most affected by it. Sanyu FM staff and Amuru youth are among those who have found their own solutions to their present predicaments.

Museveni, on the other hand, has done the opposite. He has imposed the “social distancing” mantra of the Global North upon his own national context, where food comes more often from the garden or the market than a refrigerator in the house — even for the few who are privileged enough to own such appliances. In many congested neighborhoods, several families may share space, water sources and bathrooms. Shouting at people to keep distance from one another places responsibility (and blame) for public health upon the urban poor.

Had Museveni heeded his own nation’s experience managing epidemics, he might have gleaned a lesson or two. The late physician Matthew Lukwiya guided health workers through the 2000 Ebola crisis in the middle of a war. Lukwiya convinced scared and defected professionals to return to work to save the community. At the same time, he bravely navigated the perilous bureaucracy of the Ministry of Health to pull the necessary strings ensuring adequate support was promptly rendered to victims.

“Lukwiya is still celebrated for his Dr. King-like charisma and ability to rally people toward a vision,” said Nicolas Laing, a doctor based in Lacor where Lukwiya had served. “He did this at the expense of his own life, but completely eradicated Ebola from Uganda.”

Uganda is not the only African nation to have dealt with contagious outbreaks with immense efficacy, but amidst this particular pandemic, Uganda is not exactly a shining example. Museveni’s autocratic measures are causing very real death and suffering while doing little to flatten the COVID-19 curve. As hunger, medical emergencies and brutality continue to surge, Museveni may be left with no other option than to succumb to the voices of Ugandans who offer more reasonable proposals for survival.