With unemployment nearing Great Depression levels and many still waiting on any government support, a new person-to-person relief economy is forming.

By April M. Short

The responses of governments around the world to the pandemic and its resulting economic impacts are revealing and varied. As officials enact measures to keep economies afloat and keep people from financial ruin, unprecedented relief efforts are underway. Canada’s government has promised monthly payments worth about $1,450 to anyone affected; Australia plans to give about $1,000 every two weeks to each employee of any struggling business. Many nations, big and small, have guaranteed recurring payments to all citizens until it is safe to go back to work. Italy froze all rent and mortgage payments in early March, and cities and countries around the world have considered ways to follow suit—including the U.S., which ordered reduced mortgage payments for some eligible homeowners for up to a year. In late May, the European Commission proposed an $820 billion coronavirus stimulus package, focused on investments in Europe’s “Green Deal” industries like renewable energy. Around the globe, nations are working to relieve their citizens from the sudden financial burdens as a result of COVID-19.

While the U.S. stimulus package wears the largest price tag at $2.3 trillion, and the oil industry and other mega-corporations are pumping billions of stimulus dollars through their businesses, the economy is teetering with unemployment rates nearing Great Depression levels. Individual Americans have only been promised a one-time payment of $1,200, and many have been waiting for that check for months. The unemployment system—which was expanded in an attempt to cover the fifth of Americans who are self-employed contract workers—is overloaded and rife with reports of errors. More than 30 million people have filed initial claims since mid-March, and for many the unemployment system has proved to be unresponsive.

The virus has arguably impacted the U.S. worse than anywhere else in the world, and while some Democrats have proposed additional supportive response measures like $2,000 monthly stimulus checks for all until the crisis subsides, bailouts for student loan borrowers and rent and mortgage cancellations for certain periods, Republicans have appeared uninterested in additional stimulus and the Trump administration has been pushing for an early reopening of the economy long before there is a go-ahead by health officials. It’s likely any new government relief will take time to reach people, if it happens at all.

And as the pandemic most severely impacts the same communities that have been historically exploited and oppressed by racist and xenophobic practices in this country, long-needed conversations are emerging around which industries and workers are truly essential to life’s basic functions, and how we treat and compensate those workers in our society.

As playwright V (formerly Eve Ensler) put it in an Instagram post on May 18:

“The virus is revealing the violent, broken, greed and growth systems that we have been both tolerating and forced to live with for far too long. As we #RiseInGlobalSolidarity to meet this moment, we now MUST ASK ourselves; ‘what is essential’, ‘who is essential’, ‘what would it mean to live with just what is essential’, and ‘how would we value, protect and uplift those who are doing the essential work’?”

Out of the necessity of the moment have emerged some extraordinary, citizen-led relief efforts. Mutual aid volunteers have been mobilizingacross the country since the virus hit, with those who are able bringing free groceries and other basics to the people who are hardest hit. And, as the divide between the employed and the jobless deepens in America, a sort of citizens’ fiscal relief effort has also developed. At one end of the trend are problematic top-down handouts and money giveaways by wealthy influencers on Instagram, as explored in a New York Times piecein April. At the other end of the trend is an opportunity for a longstanding, citizen-led movement toward wealth redistribution to step into the spotlight. This solidarity economy movement aims to democratize economic systems by way of localized efforts and supports the most marginalized Americans. As this crisis makes the glaring gaps and biases in our current systems impossible to ignore, some argue now is the time to push for a new, solidarity-oriented economy.

Drop Your Venmo in the Comments

With invitations from influencers on Instagram and other apps asking for people out of work to “drop your Venmo in the comments,” a good samaritan giveaway economy is developing online. Out-of-work, struggling Americans have turned to social media to ask strangers for small bailouts—like basic grocery money or help paying the rent. The trend exposes the deepening divide between the employed and the jobless in America.

As strangers are stepping in to pay for strangers’ bills, a “samaritan economy” is emerging through apps like Instagram, NextDoor and Venmo. The trend is detailed in an April article in Utah’s Deseret News by Jennifer Graham, who writes:

“Using apps like Venmo and NextDoor, people who have money are giving it to strangers who don’t. Others are paying service providers, such as hairdressers and pet sitters, for services they didn’t receive. And a nonprofit that has given cash to struggling families in Africa for more than a decade [called GiveDirectly] has launched a program to quickly get help to Americans who are spiraling toward insolvency.”

People with significant online followings have been encouraging followers in need to request financial aid from fellow followers, and comment threads across social media channels are full of requests. As Graham’s article notes, Yashar Ali, a journalist with 621,000 Twitter followers, tweeted in favor of person-to-person aid in late March in a thread that has gone viral.

Other online influencers, some of whom are flaunting their cash to spare, have been pushing the concept of giving away money in a slightly different direction, as explored in the New York Times article “Everyone Is Giving Away Cash on Instagram.” The article explores how some influencers are capitalizing on the crisis for self-promotion:

“As the coronavirus has continued to disrupt American lives and livelihoods, Instagram has been overrun with cash giveaways… Several popular personalities have offered cash to their fans in exchange for tags, follows and comments, including Harry Jowsey, a star of the new Netflix reality show ‘Too Hot to Handle’; the lifestyle influencers Caitlin Covington and Laura Beverlin; and the rapper and social media star Bhad Bhabie.”

The Times piece dives into the varying levels of transparency and self-interest of influencer giveaways during the crisis.

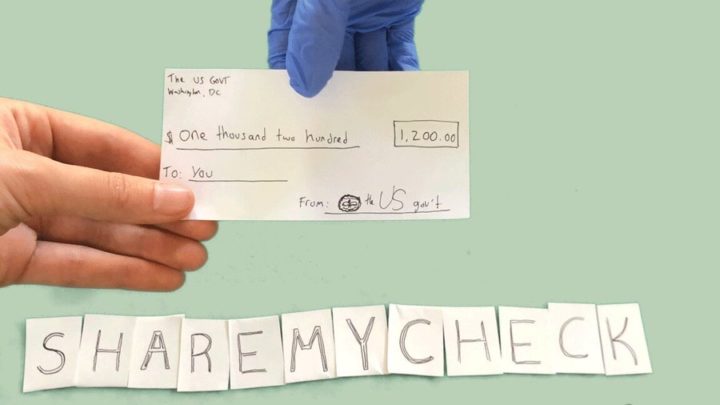

#ShareMyCheck

With the arrival of $1,200 stimulus checks, an online movement has emerged encouraging people with the means to give away part or all of their stimulus checks, to help strangers in need online. While this might have sounded like a far-fetched, radical concept to many Americans just a few months ago, today it’s trending.

GiveDirectly, the nonprofit mentioned in Graham’s article that has pivoted its efforts from focusing on Africa to focusing on those in the U.S. impacted by COVID-19, has enacted a pledge drive asking people who don’t need their federal stimulus money to give it away to those in need. The company accepts donations in any form, using credit cards, stock transfers or Bitcoin.

GiveDirectly is part of a larger trend focused on redistributing stimulus money to communities most in need. The hashtags #ShareYourCheck and #ShareMyCheck have been gaining popularity across social media channels, encouraging Americans who still have steady employment to share their stimulus checks, and any excess income, with people out of work during the pandemic.

The check sharing movement and the hashtags come from an organized effort by the New Economy Coalition (NEC), which is a network of advocacy groups across the country that are focused on developing a new economic model in the United States and beyond. This is often referred to as the “solidarity economy.” The coalition’s members include environmentalist organizations, social and economic justice activist groups, economists and others—all of whom work within their local areas to envision and enact community-based economic models that are more democratic and sustainable than the current prevalent systems.

The idea for the Share My Check campaign initially came from one of NEC’s members, Resource Generation, which is a membership community made up of young people ages 18-35, who recognize that they have benefitted from wealth or class privilege and are “committed to the equitable distribution of wealth, land, and power,” as stated on the group’s website.

Kelly Baker, a co-director of the NEC, who is based in Boston, says when she first heard about the $1,200 government stimulus checks, it occurred to her that since she still had work, she wouldn’t be putting that money to immediate use for groceries, rent or other bills.

“I thought, if I’m in that situation, possibly other people are, and it turns out that I wasn’t the only one who had that idea, which is really a great thing,” she says.

The concept was adopted by NEC’s members across the country. Since NEC already has a donation page, it funnels any donations that come from #ShareMyCheck directly to organizations that offer direct aid to people most in need.

Long before the pandemic struck, NEC has been working to identify the communities most urgently in need of economic support efforts, and funneling grant money to the organizations working directly to bring mutual aid and on-the-ground organization to those communities. They organize and divvy out donation-based grants to grantees that meet specific criteria, through their Movement Support Program fund.

“We already have this existing program [and] the resources we need to move this money,” Baker says. “So, we started the Share My Check campaign with the explicit goal to amplify the work of the Movement Support [Program] fund, and increase the amount of grants we can move through that fund directly to solidarity economy organizing.”

After the COVID-19 situation became clear, and the Share My Check campaign was born, NEC switched gears from its regular grant process to a rapid-response model. They reached out to their members and developed new criteria for a process that allows for a quicker grant process and supports the most urgent initiatives offering mutual aid and support through the pandemic.

Baker says in response to the urgency of the current moment, NEC expanded their donation collection system to allow for a wider breadth of donations, however large or small.

“We wanted to include more working-class folks in this, knowing that a lot of donors are donors who give small amounts, and who don’t necessarily find themselves in a position to give $1,200 but might be able to give $50 or something like that,” Baker says. “So we expanded our idea of what the Share My Check campaign could be, to include as many people as possible from as many walks of life as possible, knowing that the desire was there for people to support each other, and support direct service and long-term organizing.”

Melody Martínez, who lives in Portland, Oregon, is the individual giving manager for NEC and says the groups NEC is funding, and has always worked to fund, all have one thing in common: the fact that they are made up of and represent working-class people.

“These are groups that are made up of people of color, of immigrants, that span the United States and Puerto Rico,” Martínez says. “And they all work on different things, whether it’s co-op work, or farming work, or arts and culture work, or finance. They span the kind of spectrum of the world that we want to live in, where people are working collaboratively with growing food, where we’re working together to develop new systems.… It’s the kind of work for people specifically who are most impacted when we’re in an economic recession or when a crisis hits.”

Martínez notes that the NEC website includes a thorough list of all past and current donors, for anyone interested to learn more specifically about where donations and grant money from NEC and the Movement Support Program fund go.

As of mid-May, the Share My Check initiative had raised about $26,000 from individual donations ranging from $10 to the full $1,200.

While NEC began with efforts primarily focused on college campuses, since 2015 the program has been intentionally shifting toward supporting frontline groups and youth organizing groups doing solidarity work beyond college networks. Baker says the coalition was formed as a way to tie together the various existing threads around the nation that were already working toward the solidarity economy.

Baker says the current economic emergency brings the necessity of a new economy to the surface.

“The new economy is fundamentally something that starts in your community; it starts in neighborhoods, it starts in local and regional areas,” she says. “The solidarity economy… is a shift from the current status quo, the current system, to something that puts people and the planet before profit. At the New Economy Coalition, we have a pluralistic approach to what the next economic system would be. We don’t prescribe one blueprint, but rather think that there is a set of values that we can take with us and build systems and institutions around that. Those are democracy and democratic decision-making; mutual aid and solidarity; cooperation. Really, we formed our movement with the idea that the current system is not working for most people… and we’re trying to create institutions that are led by and for the community and people.”

Martínez says the NEC’s pluralistic approach to the solidarity economy includes developing an understanding of the current systems, as is necessary in order to create a new way of living in the world.

“We live in a world where there is massive income inequality, massive wealth inequality, where land and resources like water and clean air are not being equitably distributed, and not just in the U.S. but globally,” says Martínez. “So those principles of the solidarity economy—cooperation, solidarity and democracy—all of those things on their own aren’t enough. They have to be speaking together, to ensure that we have a just and sustainable system afterward.”

While the decision to share a stimulus check seems uniquely of this moment, Martínez sees it as part of a larger interest in systemic wealth redistribution that assesses equity across racial, gender, class, ethnic, and national lines.

The pandemic has brought wider public awareness of the painful shortcomings that have long existed in the current economic system. “When some of us have enough, what do we do? What do we do with that? The current system says we should keep it” for our own individual or family wealth, she says. “We should bootstrap this, you should put it in a savings account, for what might come next.” Instead, she says, NEC is arguing that people use this moment to begin to imagine how the world would look like if we all had enough to live on, and begin to create a new system based on this vision.

“Wealth redistribution is really about understanding that the way the system is now really privileges a few at the expense of so many, and in that new world, that new economy, that new place, what we could do is really redistribute this,” she says. “We can all have access and all share in the benefits of our labor, of our work.”

April M. Short is an editor, journalist and documentary editor and producer. She is a writing fellow at Local Peace Economy, a project of the Independent Media Institute. Previously, she served as a managing editor at AlterNet as well as an award-winning senior staff writer for Santa Cruz, California’s weekly newspaper. Her work has been published with the San Francisco Chronicle, In These Times, Salon and many others.