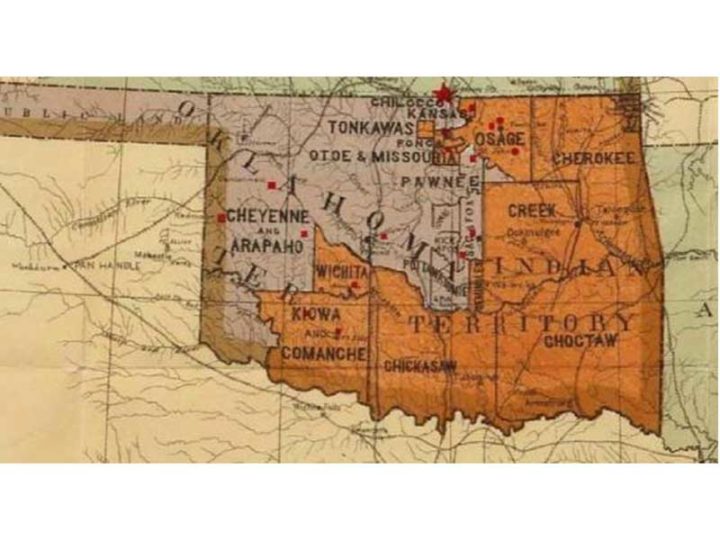

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled Thursday that about half of the land in Oklahoma is within a Native American reservation. The court ruling will have major consequences for both past and future criminal and civil cases in the U.S.

The U.S. court’s ruling hinged on the question of whether the Creek reservation continued to exist after Oklahoma, one of the 50 states constituting the United States, became a state.

The case was steeped in the U.S. government’s long history of brutal removals and broken treaties with Indigenous tribes, and grappled with whether lands of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation had remained a reservation after Oklahoma became a state.

“Today we are asked whether the land these treaties promised remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law. Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word,” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in the majority opinion.

The decision was 5-4, with Justices Gorsuch, Sonia Sotomayor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan and Stephen Breyer in the majority, while Justices John Roberts, Brett Kavanaugh, Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas dissented.

Some 1.8 million people, of whom about 15% are Native American, live on the land, which spans three million acres.

The ruling will have significant legal implications for eastern Oklahoma. Much of Tulsa, the state’s second-largest city, is located on Muscogee (Creek) land. The Muscogee (Creek) Nation cheered the court’s decision.

Dissenting opinion

In a dissenting opinion, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote that the decision “will undermine numerous convictions obtained by the State, as well as the State’s ability to prosecute serious crimes committed in the future,” and “may destabilize the governance of vast swathes of Oklahoma.”

John G. Roberts Jr. warned in a dissenting opinion that the court’s decision would wreak havoc and confusion on Oklahoma’s criminal justice system.

“The state’s ability to prosecute serious crimes will be hobbled and decades of past convictions could well be thrown out,” Chief Justice Roberts wrote. “On top of that, the court has profoundly destabilized the governance of eastern Oklahoma.”

The ruling has a number of significant consequences for criminal law in the relevant portion of Oklahoma.

The first is that going forward, certain major crimes committed within the boundaries of reservations must be prosecuted in federal court rather than state court, if a Native American is involved. So if a Native American is accused of a major crime in downtown Tulsa, the federal government rather than the state government will prosecute it. Less serious crimes involving Native Americans on American Indian land will be handled in tribal courts. This arrangement is already common in Western states like Arizona, New Mexico and Montana, said Washburn.

Then there is the issue of past decisions — many of them are now considered wrongful convictions because the state lacked jurisdiction. A number of criminal defendants who have been convicted in the past will now have grounds to challenge their convictions, arguing that the state never had jurisdiction to try them.

The case before the court, McGirt v. Oklahoma, concerned Jimcy McGirt, an enrolled member of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma who was convicted of sex crimes against a child on Creek land. In post-conviction proceedings, McGirt argued that the state lacked jurisdiction in the case and that he must be retried in federal court. The high court agreed.

The ruling will affect lands of the Muscogee and four other Oklahoma tribes with identical treaties. Civil court issues are also affected.

Jurisdiction, not land ownership

It is important to note that the case concerned jurisdiction, not land ownership.

Ruling that these lands are in fact reservations “doesn’t mean the tribe owns all the land within the reservation, just like the county doesn’t own all the land within the county. In fact, it probably doesn’t own very much of that land,” said Kevin Washburn, dean of the law school at the University of Iowa, where he teaches a course on federal Indian law, explained. “That’s not what a reservation is these days.”

Washburn compares a reservation to a county — terms that describe jurisdictional boundaries.

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter released a joint statement with the Muscogee (Creek), Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole nations on Thursday, indicating that they “have made substantial progress toward an agreement to present to Congress and the U.S. Department of Justice addressing and resolving any significant jurisdictional issues.”

Ian Heath Gershengorn, an attorney at Jenner & Block, argued McGirt’s case before the Supreme Court. He said his team was thrilled with the result and had felt optimistic knowing that Gorsuch could prove to be the deciding vote.

Gorsuch joined with the court’s more liberal members in the decision. Prior to his appointment to the high court, Gorsuch was a judge on the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which frequently sees cases involving Native American lands.

“Justice Gorsuch has made very clear in his short time on the bench that he takes the text deeply seriously,” Gershengorn said. “And I think you saw that the core of his analysis today was a textual one. We felt like we had the right argument at the right time for the right justice.”

The court decision, potentially one of the most consequential legal victories for Native Americans in decades, could have far-reaching implications for the people who live across what the court affirmed was Indian Country.

The decision puts in doubt hundreds of state convictions of Native Americans and could change the handling of prosecutions across a vast swath of the state. Lawyers were also examining whether it had broader implications for taxing, zoning and other government functions. But many of the specific impacts will be determined by negotiations between state and federal authorities and five Native American tribes in Oklahoma.

Establish sovereignty

“The Supreme Court today kept the United States’ sacred promise to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of a protected reservation,” the tribe said in a statement. “Today’s decision will allow the Nation to honor our ancestors by maintaining our established sovereignty and territorial boundaries.”

An extraordinary time

The ruling comes at an extraordinary time for Native Americans.

They are being ravaged by the coronavirus both in the soaring numbers of cases and deaths and the economic distress caused by closed casinos. But at the same moment, the U.S.-wide movement to confront systemic racism has infused new energy and attention to generations-long fights by tribal nations and Indigenous activists over land, treaty rights and discrimination.

In the past few weeks, tribal activists garnered international attention after they blocked the roads outside Mount Rushmore to condemn President Trump’s visit to what they called stolen lands. They won a fight to shut down an oil pipeline that crossed sacred ground in North Dakota. In the face of growing pressure from corporate sponsors, the Washington Redskins of the N.F.L. recently promised to re-evaluate their team name, which activists have denounced for years as racist.

On social media, people celebrated Thursday’s decision with the declaration Native Lives Matter.

Earlier, the Justice Department raised concerns about how federal prosecutors would cope with a new onslaught of cases they would be suddenly responsible for investigating. Lawyers were parsing whether the decision might affect taxes, adoption or environmental regulations on the reservation lands.

But experts in Indian law said the decision’s effects would be more muted, and would change little for non-Natives who live in the three-million-acre swath of Oklahoma that the court declared to be a reservation of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

“Not one inch of land changed hands today,” said Jonodev Chaudhuri, ambassador for the Creek Nation. “All that happened was clarity was brought to potential prosecutions within Creek Nation.”

Jonodev Chaudhuri, also a former chief justice of the Muscogee Nation’s Supreme Court, dismissed talk of legal mayhem.

He told the Tulsa World newspaper: “All the sky-is-falling narratives were dubious at best.

“This would only apply to a small subset of Native Americans committing crimes within the boundaries.”

The decision could have far-reaching implications on tribes beyond the reservation boundaries in eastern Oklahoma.

McGirt argued that Congress had created the reservation and had never clearly destroyed the sovereignty of the Creek Nation over the area, even as much of the land was parceled off to private ownership.

Forced relocation

Justice Gorsuch’s opinion, tracing that history, began: “On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise.” The reference is to the forced relocation of some 100,000 Native Americans from their home in the Southeast in the 1800s.

The opinion said that the promise was that Congress had guaranteed the Creek land for a permanent home in what became Oklahoma in exchange for forcing them from their ancestral lands in Georgia and Alabama during the 1830s.

The court was faced with the question of whether lands of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation had remained a reservation after Oklahoma became a state and the tribe’s lands were fractured and sold off and its powers of self-governance were attacked by Congress.

Some Indigenous activists and lawyers said they were not surprised that Justice Gorsuch had broken with his fellow conservatives.

On the court, he had provided the pivotal vote in favor of Indigenous rights in cases dealing with a Native American cited for illegal hunting in Wyoming, and about fuel taxes imposed on a business owned by a member of the Yakama Nation.

“Reading it, the understanding of what has happened to our people was nice to see acknowledged at this level of the government,” said Sarah Deer, a lawyer and a professor at the University of Kansas, who is also a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. “It’s not something we’ve seen from the court very often. It has a lot of meaning.”

Legal scholars

Some legal scholars said that Justice Gorsuch did not favor the tribes, but had simply adhered to the language of the treaties. For generations, tribes have been asking the U.S. to honor the written agreements they made.

Kevin Washburn said: “It’s basically 15 weeks of how the law in the United States has failed my people.”

He served as assistant secretary of Indian affairs from 2012 to 2016, and he is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma. He called the court’s ruling “a great decision.”

“For Indian people, their land is really important, and treaties are really important. They are sacred. And this reaffirms the sacredness of those promises and those treaties.”

“Now and then there is a great case that helps you keep the faith about the rule of law,” he said. “And this is one of those.”

Lindsay Robertson, who teaches federal Indian law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law, said Justice Gorsuch did just that: “It does not matter that a million-plus non-Indians live there now. It does not matter that the state of Oklahoma has been acting as if it were subject exclusively to state jurisdiction. What matters is what the language said.”

In arguing against the tribes, the solicitor general of Oklahoma took the opposite view, saying during arguments in May that “it was never reservation land, and it’s certainly not reservation land today.”

The case, McGirt v. Oklahoma, No. 18-9526, an appeal from a state court’s decision, was the Supreme Court’s second attempt to resolve the status of eastern Oklahoma.

In November 2018, the justices heard arguments in Sharp v. Murphy, No. 17-1107, which arose from the prosecution in state court of Patrick Murphy, a Creek Indian, for murdering George Jacobs in rural McIntosh County, east of Oklahoma City.

After he was sentenced to death, it emerged that the murder had taken place on what had once been Indian land. Murphy argued that only the federal government could prosecute him and that a federal law barred the imposition of the death penalty because he was an Indian.

Murphy and McGirt are expected to be retried in federal court. Legal experts said that other Indigenous people who had been prosecuted by the state for crimes on Creek land would have to ask federal courts to review their cases.

The war continues

Madonna Thunder Hawk, an organizer with the Lakota People’s Law Project, said the court’s decision and a recent federal ruling that ordered the shutdown of the Dakota Access Pipeline in North Dakota had been cause for celebration. Just not too much.

“It’s a war for us,” she said. “There are some victories, but the war continues.”

The Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears is the forcible 19th Century relocation of Native Americans, including the Creek Nation, to Oklahoma. The U.S. government said at the time that the new land would belong to the tribes in perpetuity.

The rape case

The ruling overturned McGirt’s prison sentence. He could still be tried in federal court. McGirt, now 71, was convicted in 1997 in Wagoner County of raping a four-year-old girl. He did not dispute his guilt before the Supreme Court, but argued that only federal authorities should have been entitled to prosecute him. McGirt is a member of the Seminole Nation.

An analysis by The Atlantic magazine of Oklahoma Department of Corrections records found that 1,887 Native Americans were in prison as of the end of last year for offences committed within the boundaries of the tribal territory.

But fewer than one in 10 of those cases would qualify for a new federal trial, according to the research.

Other tribes

In a joint statement, the Five Tribes of Oklahoma – Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole and Muscogee Nation – welcomed the ruling.

They pledged to work with federal and state authorities to agree shared jurisdiction over the land.

“The Nations and the state are committed to implementing a framework of shared jurisdiction that will preserve sovereign interests and rights to self-government while affirming jurisdictional understandings, procedures, laws and regulations that support public safety, our economy and private property rights,” the statement said.

Muscogee leaders hailed the decision as a hard-fought victory that clarified the status of their lands. The tribe said it would work with state and federal law enforcement authorities to coordinate public safety within the reservation.

“This is a historic day,” Principal Chief David Hill said in an interview. “This is amazing. It’s never too late to make things right.”

“This brings these issues into public consciousness a little bit more,” said John Echohawk, executive director of the Native American Rights Fund, a nonprofit organization that has spent five decades fighting for issues like tribal sovereignty and recognition. “That’s one of the biggest problems we have, is that most people don’t know very much about us.”